The Armor We Never Knew She Wore

Part I: The Mane and the Trap

For months, our six-year-old daughter, Fiona, had refused every attempt to trim her hair. It had started subtly, a mild protest—little pouts and firm shakes of the head whenever I, Sarah, brought out the scissors. My husband, Daniel, and I, initially found it amusing. “She’s got a strong sense of style,” he’d joked one evening, watching Fiona fiercely brush her reflection in the hallway mirror.

Fiona’s hair was undeniably magnificent. Thick, buoyant chestnut curls that reached almost to her waist, a vibrant cascade of color and volume that bounced behind her like a lion’s mane. Strangers often stopped us in the grocery store or the park to compliment its length and luster, and Fiona would bask in the attention, straightening her posture and offering a small, dignified smile.

But as the months passed, her resistance deepened into something fierce, bordering on panic. She’d burst into tears if we even mentioned a haircut. “It’s too cold,” she’d insist, or, “The scissors make a scary sound.” We chalked it up to a stubborn phase, like her brief insistence on wearing her bright blue rain boots everywhere, even to bed. We were so caught up in the architectural design of our own busy lives—Daniel managing complex software projects, and me, Sarah, balancing freelance design critiques—that we failed to recognize the structural flaw developing in her small world. We saw the beautiful exterior; we missed the internal stress fracture.

Then, on a dreary Saturday morning in late October, disaster struck. Fiona, having fallen asleep during our Friday night movie marathon with a half-chewed piece of pink bubble gum still in her mouth, woke up to a catastrophic mess. The gum had wound itself inextricably through a substantial section of her curls near the crown of her head, sticky, solid, and unforgiving.

Daniel, the pragmatist, initiated a full-scale rescue operation. He tried the internet’s remedies: ice cubes to freeze the sticky mass; creamy peanut butter to dissolve the polymers; and finally, a slick application of olive oil, which only succeeded in creating a greasy, pink-infused knot. Nothing worked. The gum had fused with her hair, transforming from a silly accident into an immovable fixture.

I sighed, recognizing defeat. The damage was too deep, too close to the scalp, to pick apart strand by strand. I fetched the sharp kitchen scissors, the ones usually reserved for cutting craft paper. “Honey, we’ll just need to cut a little bit,” I said gently, crouching down to meet her tearful gaze.

The moment Fiona realized what I meant, she froze, her small body locking up. Her eyes, usually sparkling and bright, instantly filled with enormous, brimming tears. “No,” she whispered, her voice barely a breath, while clutching the tangled hair with both small hands.

“Sweetheart, it’s just hair. It’s sticky. We have to take it out. It’ll grow back, and you can tell all your friends you fought a bubble gum monster,” I assured her, attempting a lighthearted distraction.

But she shook her head violently, her lip trembling so hard she looked like she might shatter. “No, you don’t understand!” she shouted, the volume of the outburst shocking us both. “If you cut it, I’ll be ugly!”

The room went utterly quiet. The only sound was the faint drip of a leaky faucet in the laundry room. Daniel, who had been wiping peanut butter off the floor, stopped dead. The scissors slipped in my sweaty palm, landing with a soft, ominous thud on the hardwood floor.

Daniel instantly knelt beside her, his large frame awkward on the floor. He didn’t look at me, his focus entirely on his daughter. “Fiona,” he said, his voice slow and heavy with confusion, “you’re beautiful no matter what. That’s nonsense.”

She cried harder, the sobs ragged and deep, unlike her usual dramatic toddler tears. These were tears of true, existential pain. “You don’t know what the girls said at school,” she sobbed, the revelation ripping through the tense silence. “They said my hair is the only pretty thing about me.”

My chest tightened, a crushing, physical sensation. I felt a sudden rush of cold, bitter air, as if a window had shattered.

Daniel’s jaw clenched, his voice suddenly hoarse, stripped raw of his usual easy logic. “Who said that? Who told you that, Em?” He used her nickname, Em, the one reserved for moments of absolute tenderness.

Fiona buried her face in her hands, the truth a flood she couldn’t stop. “Everyone laughs when I talk. They say I look funny—but my hair makes me look like a princess.”

I didn’t need to look at Daniel to know we shared the same crushing realization. The truth had hit us like a stone dropped in cold water. This wasn’t six-year-old vanity or a phase of rebellion—it was armor. Her magnificent curls were a shield she desperately believed she needed to ward off the perceived ugliness of her own self.

And if we took it away, what would she have left to shield herself with?

.

.

.

Part II: The Shattered Armor

The rest of the morning dissolved into a blur of protective instinct and simmering rage. Daniel immediately abandoned the clean-up; the mess on the floor—a mixture of peanut butter, olive oil, and melted pink gum—was insignificant compared to the psychological debris now strewn across our living room.

“Who specifically, Fiona?” Daniel repeated, his voice dangerously low. He was a man who prized data and accountability, and the problem now required an identifier.

Fiona, exhausted from the sobs, only shrugged miserably. “Chelsea. And Olivia. And the others.”

Chelsea. A name that brought up an immediate, unwelcome recognition. Chelsea Miller, the daughter of our neighbor, Brenda. A bright, sharp-eyed girl whose mother had once subtly criticized Fiona’s choice of mismatched striped leggings. The micro-aggressions of adulthood, I realized with chilling clarity, were only scaled-down versions of the cruelties inflicted in elementary school.

“The first thing is the hair,” I announced, forcing myself into functional mode. “We can’t solve the deeper problem until we remove the immediate source of panic.”

Fiona flinched as I picked up the scissors again. “No! It will be a big hole! They’ll see it!”

“It won’t be a hole, honey,” I said, my voice firm but gentle. “We are going to make it an accent. We’re only cutting the part where the gum is. And then, we are going to make the rest of your hair a little shorter, so it all looks intentional and beautiful. We are not hiding. We are re-designing.”

My training as an architectural analyst kicked in. When a structure fails, you don’t abandon the site; you find the deepest foundation and rebuild. This wasn’t just a haircut; it was a foundational repair.

We moved to the bathroom. Daniel held Fiona, his arms wrapped securely around her small waist, providing a physical anchor. He didn’t say anything, but his chin rested on the top of her head, and I could feel the tension radiating off him.

I approached the task with meticulous care, separating the gum-infused lock. It took a single, swift snip. The section of hair, maybe three inches long, dropped onto the white vanity countertop, heavy with gum and oil.

Fiona let out a tiny, choked sob. “It’s gone,” she whispered, staring at the small, uneven patch where the hair had been.

“Now, watch this,” I murmured. I spent the next twenty minutes using the small shears to taper and blend the surrounding curls, giving her a modern, layered bob that stopped just at her shoulders. It was a stunning transformation. The shorter length made her natural curl pattern pop with tighter spirals, framing her face beautifully.

I turned her toward the mirror. She looked different—less like the fairytale princess she had aimed for, and more like a fierce, stylish young woman. But the fear in her eyes hadn’t vanished.

“Do you see the hole?” I asked.

She touched the newly cut spot cautiously, then ran her fingers through the buoyant layers. “No,” she admitted, surprised. “It looks… curly.”

“It looks like Fiona,” Daniel affirmed, kissing her temple. “It looks brave. You fought the gum monster, and you won. Now, we are going to fight the silly-talk monster.”

Once Fiona was distracted by a new art project, Daniel and I retreated to the kitchen, the reality of the situation settling heavily around us.

“Six years old, Sarah,” Daniel said, running a hand through his perpetually neat, short hair. “Six. I thought we were worried about her sharing crayons, not about her self-worth being tied to her follicular structure.”

“They targeted her,” I said, pacing the length of the kitchen counter. “They found the thing she valued most and convinced her it was the only thing valuable about her. It’s calculated cruelty. It’s not just teasing, Daniel. This is systematic dismantling.”

My rage was cold and sharp. As an architect, I knew the difference between accidental damage and sabotage. This was sabotage.

“We need to identify the variables,” Daniel murmured, already in problem-solving mode. “I’m calling Principal Thompson first thing Monday. We need names, we need a zero-tolerance policy confirmed, and we need the school to mediate a formal apology. I will handle the institution.”

I shook my head immediately. “No. That’s your programmer’s instinct, Daniel—fix the external bug. But the bug is internal now. If you go in guns blazing, Principal Thompson will do what all administrators do: circle the wagons. He’ll call it ‘typical childhood dynamics,’ and we’ll get a scripted meeting that accomplishes nothing but making Fiona feel more exposed.”

“So, what? We do nothing?” he challenged, his frustration evident.

“We do reconnaissance,” I countered, leaning my palms on the cool granite. “I need to understand the environment that created the problem. I need to talk to her teacher, Ms. Clara. I need to watch how she interacts at school drop-off. I will handle the human firewall. You handle the analysis.”

This disagreement—the Architect (Sarah, focused on foundational integrity and emotional structure) versus the Programmer (Daniel, focused on systems, debugging, and immediate fix)—was familiar, but never had the stakes been so high. This time, our marriage and Fiona’s future depended on our ability to merge our strategies.

Part III: The Architect and the Programmer

The following Monday was a masterclass in contrasting parental styles.

Daniel, in a clean button-down shirt and his sharpest business tone, secured an immediate meeting with Principal Thompson. He went armed with a meticulously organized binder, titled: Fiona Lawrence—Behavioral and Psychological Contextual Analysis. It contained: transcripts of our conversation with Fiona (using my memory, not recordings), a printout of child development articles on social aggression, and a proposed, three-step mediation plan.

He returned two hours later, utterly deflated.

“Thompson was useless,” Daniel reported, unpinning his tie and slumping onto the sofa. “He read the situation like an HR manual. He was extremely sympathetic, insisted he would have a ‘quiet, restorative conversation’ with the relevant parties, and then immediately pivoted to the fact that they hadn’t received any formal reports of bullying.”

“They never do,” I stated, handing him a glass of water. “Bullying among young girls is silent, structural, and done by implication, not by punching someone on the playground. Did he give you names?”

“He confirmed Chelsea Miller was involved but insisted he couldn’t share details about other students due to ‘privacy protocols.’ He blamed the parents for not raising their children to be kind, which I found deeply unprofessional.” Daniel pulled out a clean sheet of paper. “I’m building a case, Sarah. I need hard data. I need witnesses.”

While Daniel was battling the institutional bureaucracy, I was observing the human ecosystem. I spent three days lurking near the periphery of the playground at pick-up time, not as Fiona’s mother, but as an analyst.

Fiona, with her newly trimmed, bouncy curls, looked nervous but determined. She walked with her head slightly lower than usual. I watched as she approached her usual group of friends. Chelsea Miller, instantly recognizable by her confident posture and perfectly styled pigtails, was holding court.

When Fiona joined the edge of the group, Chelsea barely glanced up. “Oh, look, Fiona cut her hair,” she announced, loud enough for the three surrounding girls to hear. “It’s kind of short now. I guess the gum won.”

A small, insidious ripple of giggles spread through the group. Fiona’s face flushed red, and she retreated immediately, walking over to a quiet corner of the playground and pretending to be deeply interested in a discarded pinecone.

I felt a surge of cold fury so intense it made my hands tremble. It wasn’t just a comment; it was a power play, a clear, immediate confirmation that the armor was the target.

The next day, I approached Ms. Clara, Fiona’s primary teacher. Ms. Clara was a kind, overwhelmed woman in her late twenties who seemed to genuinely care but was constantly battling thirty energetic children and the curriculum requirements. I didn’t approach her about the bullying directly.

“Ms. Clara,” I began, waiting until the last child had been picked up, “I’m worried about Fiona’s confidence. She mentioned that she feels nervous about talking in class.”

Ms. Clara sighed, rubbing her temples. “Fiona is a sweet girl, Sarah. Very bright. Her imagination is beautiful. But, yes, she has become very quiet recently. The other girls—Chelsea, especially—can be… dominant. I’ve noticed a lot of eye-rolling when Fiona speaks about her imaginary creatures or her complicated games.”

This was the key insight I needed. The bullying wasn’t about the hair; the hair was the excuse. The bullying was about Fiona’s imaginative, sometimes quirky personality—the very traits we loved—which Chelsea saw as a threat to her social dominance. The hair was merely the convenient weapon.

“The eye-rolling is subtle enough that if I correct it, I look like I’m micro-managing their social lives,” Ms. Clara confessed, dropping her voice. “But I see the dynamic. Fiona’s withdrawn, and when she does speak up, she self-edits. I’ve tried pairing her with other kids, but Chelsea controls the narrative.”

I left the school knowing Daniel’s formal, external strategy was correct for accountability, but my human strategy was critical for healing. We couldn’t just punish the bully; we had to empower the victim to exist without needing armor.

Part IV: The Echoes of the Playground

The next two weeks were agonizing. Daniel devoted his evenings to building what he called “The Social Climate Mapper.” He created a custom dashboard detailing:

-

Incidence Reporting: Every witnessed act of micro-aggression (recorded by me).

School Policy Review: A detailed analysis of the school’s official anti-bullying policy versus their actual, documented response to low-level social aggression (zero documentation).

Witness Identification: Cross-referencing playdate schedules, birthday parties, and class rosters to identify the parents of the “others” who were complicit in the laughter.

He discovered that the school’s online incident form only had fields for physical violence or verbal threats—nothing for emotional manipulation or social exclusion.

“The system is designed to ignore subtle cruelty, Sarah,” Daniel announced one night, slamming his laptop shut. “They only log the stuff that leaves a bruise. The social-emotional injuries are outside their defined parameters, which means, according to the data, no bullying is happening.”

Meanwhile, I was dealing with Fiona’s unraveling self-perception. She stopped drawing her fantastical creatures. She chose muted, gray clothes instead of her usual bright, mismatched outfits. She’d spend long stretches staring at her reflection, touching her now-short hair with a profound sense of loss.

“I feel naked, Mom,” she confessed one evening, curled in my lap. “The princess is gone. Now I’m just… Fiona.”

The honesty was a punch to the gut. The name “Fiona”—her own identity—had become synonymous with “ugly” and “funny-looking.”

“Fiona is a warrior,” I told her fiercely, holding her shoulders. “Fiona is the one who goes on adventures. The princess sits in the tower and waits. The warrior builds her own path.”

She looked skeptical. “But the warrior needs a shield, too.”

This led to the deepest conflict between Daniel and me.

“We have to talk to Brenda Miller,” I insisted. “We have to go to the source. The problem is Chelsea’s cruelty, and we need to make Brenda accountable for her daughter’s behavior.”

“Absolutely not,” Daniel countered, his voice sharp. “We’ve seen Brenda. She’s brittle. She’ll minimize, deny, and turn it back on Fiona. ‘Fiona needs to toughen up.’ That’s what she’ll say. We cannot risk more trauma exposure for Fiona. We take the high road. We fix the system, not the individual. We present our findings to the School Board, bypassing Thompson, and force them to mandate an evidence-based Social-Emotional Learning (SEL) program.”

“That’s an eighteen-month solution, Daniel! Fiona is bleeding now! This isn’t a coding bug; this is a six-year-old child who thinks she’s worthless! We need a human conversation!”

Our arguments became taut, strained exchanges held in whispers after Fiona went to bed. I accused him of hiding behind his logic; he accused me of being reckless with my emotions. But underneath the anger was a shared terror: we were failing to protect the most vulnerable part of our lives.

The breakthrough came unexpectedly, through my work. I was reviewing the preliminary drawings for a new community center—a building designed to maximize natural light and open, flexible social spaces. The architect had called the design concept “Internalized Strength.”

I realized that was exactly what Fiona needed: internalized strength.

I sat Daniel down and showed him the building plans. “We are approaching this wrong,” I said, pointing to the structural framework. “We keep trying to build an external wall around her. We need to stop focusing on the attack (Chelsea) and focus on the load-bearing elements (Fiona’s identity). We fix the foundation first, then we deal with the external threat.”

Daniel looked at the blueprint, and the logic finally resonated. Data and structure working together.

“We rebuild her confidence from the inside out,” he conceded. “I’ll put the School Board presentation on hold. What’s step one?”

“We find something that is unequivocally and undeniably Fiona’s, something that she loves, that has nothing to do with her appearance, and that Chelsea can’t touch.”

Part V: The Unburdening

Fiona had always loved building things. Not just with LEGOs, but with whatever she found: blankets, pillows, shoeboxes, and tape. She was a natural architect, a builder of worlds.

We bought her a complex set of magnetic building tiles, the kind that require spatial reasoning and a lot of planning. We didn’t frame it as therapy or a skill-building exercise; we framed it as a shared project: building a miniature city for her imaginary creatures.

Initially, she resisted. She kept touching her short hair, retreating into quiet observation. But Daniel, recognizing her programmer’s mind, started to engage her on a purely structural level.

“Fiona, if this tower is ten blocks high, where do you need to place the cross-support so the wind doesn’t take it out? Look at the load distribution.”

The analytical language captured her attention. Slowly, tentatively, she started building. She wasn’t just stacking; she was designing. She designed a multi-level fortress with interlocking chambers, a geodesic dome for her “Sky Dragon,” and a cantilevered bridge connecting two parts of the carpet.

As she worked, she talked—not about the girls at school, but about the physics of the tiles, the geometry of the angles, and the elaborate backstories of the imaginary inhabitants. Her voice, once choked and quiet, began to regain its natural, melodic resonance. She was talking because she was solving, and the confidence she gained in her mind began to replace the fear in her heart.

One afternoon, Daniel was documenting her construction with his phone. “That bridge is brilliant, Fi. You figured out the perfect counter-leverage.”

Fiona looked up, genuinely proud. “The bridge has to be strong because the trolls try to break it,” she said, her eyes alight with the narrative. “It doesn’t matter what the trolls say about the bridge; it only matters if it can hold the weight.”

That single sentence—a metaphor born from her own structural engineering—was the turning point. She had articulated the essence of resilience.

With Fiona’s confidence visibly stabilizing, we knew we had to execute the external defense plan. We had rebuilt the internal structure; now we needed to fix the external environment.

Daniel finalized his presentation, a twenty-page deck titled: “Erosion of Social-Emotional Integrity: A Data-Driven Proposal for SEL Reform.” It meticulously demonstrated how the school’s policy vacuum allowed Chelsea and her cohort to operate undetected. He included Ms. Clara’s anonymous confirmation, my structural observations of the playground dynamic, and his analysis of the school’s non-responsive incident reporting system. It was cold, clinical, and utterly damning.

I, meanwhile, handled the parental diplomacy. I reached out to Brenda Miller, not with a confrontation, but with a neutral, professional request.

“Brenda, I need to talk to you about a structural issue at the school that is impacting both our daughters. I’m giving a presentation to the Board, and I want you to see the data before it goes public.”

Brenda, true to Daniel’s prediction, was initially defensive. She arrived at our house stiff and armed, ready to defend Chelsea’s ‘spirited’ nature.

I did not mention the hair. I did not mention ‘ugly.’ I used Daniel’s data.

“Chelsea is a leader, Brenda,” I began, projecting authority. “But she is currently leading her peer group to create a hostile learning environment. The school’s system, or lack thereof, has empowered her by failing to provide appropriate social feedback. Daniel’s data shows that Chelsea is operating in a policy void where the only social consequences are popularity gains. This is dangerous for her, too.”

I showed her the chart on the erosion of Fiona’s participation—a tangible representation of the damage. I showed her the policy gap.

Brenda, a high-powered realtor, understood policy and consequence. She looked at the clinical evidence, not the emotional plea. For the first time, she saw her daughter’s behavior not as a trivial social spat, but as a documented risk factor.

“I… I didn’t realize it was systematic,” she admitted, her voice soft. “I thought they were just being girls. I will talk to Chelsea. And I want to read the full proposal.”

The conversation was not a final victory—Brenda’s apology to Fiona was halting and awkward—but it was an acceptance of responsibility, the structural repair beginning at the parental level.

Part VI: The Recalibration

Two months after the gum incident, Daniel delivered his presentation to a visibly nervous School Board. He didn’t ask for Chelsea to be suspended or for Thompson to be fired. He asked for a mandate: a fully funded, evidence-based Social-Emotional Learning curriculum for K-2, implemented by the start of the next semester, with new reporting metrics that tracked social exclusion and non-verbal aggression.

The Board, terrified of the liability Daniel’s analysis had laid bare, passed the measure unanimously. It was a massive, quiet victory. The system had been forced to recalibrate.

The real test, however, was Fiona.

The week after the Board meeting, Fiona returned to school after a short holiday break. She was wearing a brightly patterned top, her short, buoyant curls framing a face that was more open and expressive than I had seen in months.

I watched at drop-off. Chelsea, having been given a sharp, parental correction, approached Fiona tentatively.

“Your hair is still short,” Chelsea said, the comment delivered in her usual superior tone, trying to reclaim dominance.

Fiona didn’t flinch. She was standing next to her new project: a meticulously drawn blueprint of her magnetic tile city taped to her cubby.

She simply ran a hand over her curls—not clutching them, but acknowledging them. “Yep,” she replied, completely neutral. She then turned her focus to the blueprint. “I’m building a new tower for my city. It needs a shear wall to resist the horizontal load.”

Chelsea, who had only ever cared about appearances and social hierarchy, had no answer for shear walls and horizontal loads. The comment about the hair—her primary weapon—had failed to land. She stood there, momentarily stunned by Fiona’s utter lack of reaction, before shuffling off.

Fiona had discovered her new armor: competence. She had internalized her strength, realizing that her value lay in her brilliant mind and her capacity to create, not in the length of her curls.

Later that day, Ms. Clara called me. “Sarah, I just wanted to tell you that Fiona gave an impromptu presentation on ‘Structural Integrity in Miniature City Design’ during free time. Every child was silent. Even Chelsea. Fiona’s confidence is soaring. Her voice… it’s back.”

The Architect of Anxiety was finally at rest. I had spent months terrified that I couldn’t protect my child from the cruelty of the world, but I realized my job wasn’t to shield her from the fire—it was to teach her how to build an internal furnace.

Daniel and I sat on the porch that evening, watching the city lights come on.

“We won the war on two fronts,” Daniel mused, leaning back. “We fixed the environment, and we fixed the internal software.”

“We didn’t fix the internal software,” I corrected gently. “We showed her that she had the source code for strength all along. The hair was a beautiful, but fragile, piece of exterior architecture. Now, the foundation is the integrity of the design itself.”

Three years later, Fiona, now nine, still has beautiful hair—it’s long again, but she cuts it when she chooses. She wears bold, colorful clothes. She still loves her imaginary creatures and her magnetic tiles, but now she also loves science club.

She rarely speaks of the gum or the girls who said she was only pretty because of her hair. It is not a trauma to be avoided, but a memory of a battle won.

One afternoon, she came home from school, tossing her backpack onto the floor. “Mom,” she said, her voice filled with a cheerful impatience, “can you help me design a better base for my newest model? The weight distribution is all wrong, and I need a better foundation.”

I looked at my daughter, her face open, confident, and utterly unarmored.

“Yes, absolutely,” I said, walking over to the table to join her. “Let’s build something strong, Fiona. Let’s make a structure that can hold any weight.”

The silence in our home was no longer the quiet of unspoken shame or fear. It was the unburdened, resonant silence of peace—the sound of a strong foundation, built to last.

News

FORRESTER WAR! Eric Forrester Shocks Ridge By Launching Rival Fashion House—The Ultimate Betrayal?

👑 The Founder’s Fury: Eric’s Rebellion and the Dawn of House Élan 👑 The executive office at Forrester Creations, the…

The Bold and the Beautiful: Douglas Back Just in Time! Forrester Heir Cheers On ‘Lope’ Nuptials

💍 The Golden Hour: Hope, Liam, and the Return of Douglas The Forrester Creations design office, usually a kaleidoscope of…

REMY PRYCE SHOCKER: Deke Sharpe’s Final Rejection Sends Remy Over the Edge—New Psycho Villain?

💔 The Precipice of Madness: Remy’s Descent into Deke’s Shadow 💔 The silence in the small, rented apartment was a…

Alone and Acting? B&B Villainess Caught in Mysterious Performance After Dosing Her Victim!

🎭 B&B’s Secret: The Ultimate Deception The Echo Chamber of Lies The Aspen retreat—a secluded, glass-walled cabin nestled deep in…

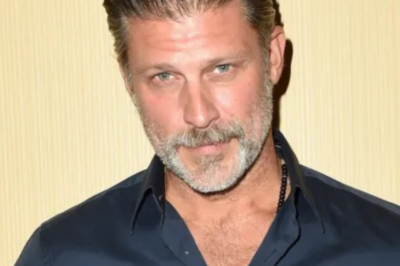

Beyond the Gates Cast Twist! Beloved Soap Vet Greg Vaughan Confirmed as New ‘Hot Male’ Addition!

🤩 Soap Shock! Beyond the Gates Snags a ‘Hot Male’ — And It’s [Insert Drum Roll]… Greg Vaughan! The Mystery…

Brooke & Ridge: B&B’s Reigning Royalty or Just a Re-run? The ‘Super Couple’ Debate!

👑 Brooke & Ridge: Are They B&B’s Ultimate ‘Super Couple’ or Just Super Dramatic? A Deep Dive into the ‘Bridge’…

End of content

No more pages to load