Bruce Springsteen Reveals His Paths Not Taken

Bruce Springsteen believes that an album is “a snapshot of who you are and where you stand at a particular point in your life.” With the release of “Tracks II,” he adds seven full albums to his musical legacy.

“The past always weighs on me,” Springsteen reflected one afternoon in April, speaking from the sitting room next to his Thrill Hill home studio in New Jersey—a space where he can create music whenever inspiration strikes. “Our pasts play a huge role in shaping who we are and what we’re chasing. That’s a theme I keep returning to, always rewriting, always trying to get it right.”

Next Friday, Springsteen will unveil “Tracks II: The Lost Albums,” an extensive collection of mostly unheard songs from earlier chapters of his career. Unlike his 1998 box set “Tracks,” which featured demos, alternate takes, and unreleased material spanning back to the ’70s, “Tracks II” is organized as seven distinct albums—83 songs in total, 74 of them never before released.

Growing up in the era of vinyl, Springsteen sees an album as “a coherent set of songs that, together, become greater than the sum of their parts,” he explained. “They reflect and amplify each other, creating new meanings in their interplay.” For him, a record is exactly that—a record of a moment, a genre, a state of mind.

As he prepared this sweeping retrospective, the 75-year-old, long viewed as a symbol of America, found himself also confronting the political realities of the present day.

During his current tour of Britain and Europe, Springsteen has given recurring, forthright speeches onstage, and released them immediately online in a six-track EP. Introducing songs like “Land of Hope and Dreams,” about immigrant aspirations, and “My City of Ruins,” about urban neglect, Springsteen has been directly denouncing the Trump administration as “corrupt, incompetent and treasonous,” and warning about “an unfit president and a rogue government.”

Before the tour, I visited Thrill Hill. “Welcome to the House of a Thousand Guitars,” Springsteen said with a chuckle. It’s a long, sunlit shed holding a 64-track console and orderly rows of guitars, drums and keyboards, directly attached to a garage full of shiny cars and motorcycles. The walls of the studio entrance are lined with framed outtakes from the photo sessions for “Born in the U.S.A.” that show him clowning around with the saxophonist Clarence Clemons, who died in 2011. A whiteboard listed song titles from an album in progress by the E Street Band member Patti Scialfa, Springsteen’s wife.

I asked to see “the vault” — his recorded archives. It’s just a nondescript server in a closet, but it holds terabytes of digital files. His master tapes, from back in the analog era until now, remain in a secure Iron Mountain storage facility.

Springsteen was still choosing a tour set list. He wanted one “that addresses our current situation,” he said. “It’s an American tragedy.”

“I think that it was the combination of the deindustrialization of the country and then the incredible increase in wealth disparity that left so many people behind. It was ripe for a demagogue,” he added. “And while I can’t believe it was this moron that came along, he fit the bill for some people. But what we’ve been living through in the last 70 days is things that we all said, ‘This can’t happen here.’ ‘This will never happen in America.’ And here we are.”

Still, Springsteen said he has hope: “Because we have a long democratic history. We don’t have an autocratic history as a nation. It’s fundamentally democratic, and I believe that at some point that’s going to rear its head and things will swing back. Let’s knock on wood.”

Wearing a long-sleeve khaki T-shirt and camouflage pants, Springsteen spoke about his career as the sum of impulses, intuitive choices and a determination to stay productive — far from a master plan. “I kind of work from the inside out,” he said. “I don’t have a concept before I make a record or anything. I’m just working on what I’m feeling at a given moment. And that can go anywhere.”

He has gone through yearslong stretches of not writing songs at all, he said. Then he has written whole albums in a matter of weeks. “I’m a soul miner,” he said. “So I’m down in the mine and I’m chipping away. And very often I’m getting nothing, nothing, nothing — more often than not. Nothing, nothing, nothing. And then you hit a vein. And when you hit that vein, Bang! Things come pouring out. And you’ve struck some gold, musical gold. And then you’ll play through that vein. And then you’re back. Nothing, nothing, and you’re looking for another vein.”

It’s a job that he still doesn’t control. “Nobody can explain that moment when you breathe life into the characters in your music, in your songs,” he said. “It comes up deeply from your subconscious and your life experience. And the alchemy of that moment remains a mystery of the mind, soul and heart.”

For “Tracks II,” Springsteen and Ron Aniello, his producer and multi-instrumentalist sideman since 2010, optimized the sound quality and occasionally added instrumental parts to the old recordings. But Springsteen “didn’t re-sing anything,” Aniello said in a later telephone interview. “All those records have those vocals from that era, whenever it was.”

Six of the so-called “lost” albums were drawn from studio projects that delved into particular styles: low-fi, country, Mexican ranchera, retro pop. The seventh album, “Perfect World,” is a ringer. It’s a compilation of rock songs that Springsteen recorded from the 1990s into the 2010s, included to give longtime fans the meaty rock they expect from the Boss. One of its songs, “Rain in the River” — a stomping murder ballad — has some of the most primal vocals of his entire catalog.

The lost albums sat in Springsteen’s vault until now because he sensed the timing was not right. “I believe I’m engaged in a conversation with my audience that has a certain ebb and flow as to when records are released,” he said.

Springsteen has preferred to record in houses and home studios with natural light and windows since 1977, when, he said, a New York City blackout had him groping his way out of Studio B at the Record Plant in total darkness. And home studios have been a vital part of his songwriting since “Nebraska,” the album he chose to release in 1982 using his unadorned, lo-fi demo recordings instead of muscular full-band takes with the E Street Band. The four-track Teac Tascam 144 Portastudio he used for “Nebraska” is now at the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame.

Image

Springsteen outside his childhood home. “Something I’ve carried with me my whole life — you do have a certain survivor’s guilt. Maybe it’s just the success you’ve had — your ability to leave those places, as I have throughout my life, and travel the world.”

“It was a lo-fi record before there were lo-fi records,” Springsteen recalled. “People were trying to make their records sound as good as they could. So that’s why the debate about putting it out at that time was so great, because there was nothing to compare it to. But there was something about it that was deeply felt.”

Erik Flannigan, who wrote the extensively researched liner notes for “Tracks II,” said, “‘Nebraska’ was the moment where he realized he could record and write on his own, and it wasn’t always with the intention of going on to finish recordings with the band. The writing and recording became one singular process.”

The bulk of “Tracks II” grows out of Springsteen working solo, as a one-man studio band, as he has since the 1980s. He’ll record with a rhythm track, “basically a drum machine of some sort or maybe just a click, an acoustic guitar and my voice,” he said. “Then I run around and I play all the instruments. I play the keys, I play bass, I play the guitars, and the synthesizers — just to see, to give me an idea.”

“If he’s doing a demo, it’s done in an hour,” Aniello said. “It’s like, ‘I’ll try a piano, I’ll throw this in,’ and it’s all just one take. It’s all very messy. He’s not going for takes — there’s plenty of time for that later.”

The earliest recordings on “Tracks II” are “The L.A. Garage Sessions ’83” — sparse, lo-fi songs that Springsteen recorded by himself, using a drum machine. Since many fans have heard them on bootlegs through the years, he didn’t change anything. The songs retain the skeletal approach of “Nebraska,” and the lyrics conjure a new collection of haunted, left-behind characters. But instead of releasing those sessions at the time, Springsteen chose to go big. He put out the arena-scale rock hits of “Born in the U.S.A.,” the songs that made him a superstar.

“I can remember how in flux I was at that moment,” he said, “and how ambivalent I was about ‘Born in the U.S.A.,’ and whether I wanted to go in that direction and put that out next.” Now, he noted, he’s glad he did.

Among the lost albums, the one that came closest to being released when he completed it was Springsteen’s “Streets of Philadelphia Sessions.” He began its songs in 1993, when experiments with a drum loop and brooding synthesizer chords turned into “Streets of Philadelphia,” the song that would win him an Academy Award.

Using drum loops was an idea he drew from West Coast hip-hop, while “that dark synthesizer that I favor, I still use it today,” he said. “It always reminds me of dark clouds, or something ominous that’s underneath everything else. It’s sort of the underbelly of your stories.”

What he calls the “trance-like, dreamy” sound led him to write a set of songs about estrangement, betrayal and desolation. He recorded solo and then, late in 1994, added a few other musicians. The album was fully mixed and tentatively scheduled to appear in 1995. Then Springsteen had second thoughts.

“This would’ve been my fourth record in a row about relationships,” he wrote in “Born to Run,” his memoir. “A not-fully-realized record around the same topic felt like one too many.”

Around the same time, Springsteen had reunited with the E Street Band to record a handful of new songs for a greatest-hits set. So “Streets of Philadelphia Sessions,” which now sounds like a dark gem, was shelved.

Assembling “Tracks II” began in 2018, when Springsteen decided to revisit the tracks that became “Somewhere North of Nashville.” They’re twangy, upbeat, often comic songs; one, “Delivery Man,” is about a truckload of chickens gone awry. Surprisingly, the songs were recorded while Springsteen was making “The Ghost of Tom Joad,” his somber 1995 album about marginalized people struggling to get by in California.

By day, Springsteen and a small band romped through live-in-the-studio takes of the songs on “Somewhere North of Nashville.” Then, after a dinner break, they worked on the “Tom Joad” songs by candlelight. Marty Rifkin, the pedal steel guitarist who’s front and center on “Somewhere North of Nashville” and eerily atmospheric on “The Ghost of Tom Joad,” recalled, “It was a beautiful thing — both smiling all day and feeling for the characters he wrote about at night.” He added, “During the day, I had to really dig in and hit the gas pedal hard. And then at night it was the complete opposite.”

The songs on “Inyo,” from mid-1990s sessions, would have been a folky sequel to “The Ghost of Tom Joad.” Some are openly modeled on Mexican styles and had Springsteen researching history; in a few, a full mariachi band suddenly arrives. “When I went to California, obviously there was a large migrant culture,” Springsteen said. “I was interested in the history of it, because I felt that this is the future of the United States — which it has become.”

Springsteen recalled growing up near camps of migrant Southern farmworkers in New Jersey. He and his grandfather, who ran an electronics shop, would visit them to sell cheap refurbished radios. Now, many of the migrant farmworkers are Mexicans. “There’s a large migrant population that lives and has altered Freehold in a very vibrant way,” he said.

He turned again to the current moment: “There are communities all across America now that have taken in immigrants and migrant workers. So what’s going on at the moment to me is disgusting, and a terrible tragedy.”

In 2005, Springsteen agreed to provide soundtrack music — songs and instrumentals — for “Faithless,” a “spiritual Western” based on a book whose title he declined to reveal. He wrote and recorded most of the music by himself in two weeks, with a foundation of hymnlike piano and bluesy slide guitar. Two decades later, the film is still, as Hollywood says, “in development.” But the songs gave Springsteen — who calls himself a “lapsed Catholic” — the opportunity to directly ponder faith and divinity.

“I had an hour of religion every single morning from when I was 6 years old until I was 12, 13,” he said. “They steeped you in the Bible and ideas of damnation and redemption. When you get that at that age, it stays with you your entire life. Luckily I was able to turn it into lyrics and concepts. There’s a lot of references to religious imagery in a lot of my music. So it’s ended up being quite a positive effect, on my writing at least. And a difficult effect on my life.”

Lately, he said, he has picked up that thread again. “I’ve written a few songs recently that are different from anything I’ve written before, and explore that part of my own spiritual experience and upbringing a little deeper.”

Image

Image

“I’m a better man when I’m working,” Springsteen said. “I feel like I’ve got plenty of work left in me, and our band does too.”

The most unexpected “lost album” may well be “Twilight Hours,” with songs that Springsteen recorded during the sessions for his 2019 album “Western Stars.” That LP embraced plush arrangements — rich strings, gleaming guitars — in songs about characters who feel compelled to keep moving. It also subtly expanded Springsteen’s harmonic palette, particularly with chords long associated with jazz and easy-listening music rather than rock: major 7th chords. On “Twilight Hours,” he revels in them.

“If there was someone who came into a session or was new in the band, Steve and I used to joke that the E Street Band never plays a major 7th chord,” Springsteen said, referring to Steven Van Zandt. “But then I got into Jimmy Webb and Burt Bacharach and I realized, Whoa! They’re very effective inside of a certain type of writing.”

Playing with a new set of chords “gave me a whole insight into a different type of songwriting,” he said. “‘Twilight Hours’ is filled with modulations, transitions, major 7th chords, a lot of musical types of things that I’d never used before. It was fun writing in basically your classic American songbook genre and seeing what I came up with.”

In those sumptuous settings, many of the narrators on “Twilight Hours” are desperately lonely guys. “All the love songs are doomed, which is my specialty perhaps,” Springsteen said with a half-smile. “But I had a long history of depression and mental illness in my family. My father struggled with a very serious mental illness through most of his life. I got it in the blood, so it affected me.”

He added, “A lot of my music deals with the idea of American isolation, which pours out of the streak of individualism that is a part of the country’s personality. And also out of depression. You feel very isolated and alone. So I have a lot of characters who are fundamentally loners, which is a big part of my personality.”

Through the entire collection, one theme keeps reappearing: the inescapable shadow of the past. It’s in “Richfield Whistle” on “The L.A. Garage Sessions ’83”; it’s in the elaborately orchestrated “High Sierra” on “Twilight Hours.” Pausing for a moment, Springsteen said the idea reflected his lifelong closeness to his hometown, Freehold.

“I still live 10 minutes from my hometown,” he said. “In Freehold I know the mayor, I know the priest at St. Rose of Lima, I know the guy who runs the diner. I still feel, at this late date, very connected to the community and people I grew up with.”

Image

“Nobody can explain that moment when you breathe life into the characters in your music, in your songs,” Springsteen said. “It comes up deeply from your subconscious and your life experience.”

He added, “Something I’ve carried with me my whole life — you do have a certain survivor’s guilt. Maybe it’s just the success you’ve had — your ability to leave those places, as I have throughout my life, and travel the world. But that’s always there hanging beside you.”

In 2021, Springsteen sold the rights to his catalog to Sony Music Entertainment for a reported $550 million. He said it hadn’t changed his relationship to his songs — or diminished his work ethic. “I saw everybody selling,” he said. “So I figured that it was the right time, and I went to Sony. They have been incredibly discreet with the way they’ve used it. And they will very often run things by me, which they don’t technically have to do.”

“Tracks II” won’t be the end of Springsteen’s archival releases. “‘Tracks III,’ that is finished,” he revealed. “It’s basically what was left in the vault,” he said, which was material from as far back as his 1973 debut, ‘Greetings From Asbury Park, N.J.,” and as recent as last year. “So there was a lot of good music left. There are five full albums of music.”

Springsteen continues to write new songs that aren’t afraid to act their age. “I get together every season with all the guys that played in local bands in Freehold. The guys that are left, we have a pizza afternoon,” he said. “But it’s always like, OK, who’s missing now?”

His 2020 album “Letter to You” and the tour that followed openly faced up to aging and mortality, acknowledging a lifetime in rock. “That’s basically the artist’s labor,” he said. “You contextualize experience and assist people in making sense of the world around them and their own lives. And give them a good tune at the same time — something to dance to.”

And even as he looks back into his catalog, he’s looking ahead to new songs. “I’m a better man when I’m working,” he said. “I feel like I’ve got plenty of work left in me, and our band does too. Our band’s in great shape, and we carry on.”

News

“I Came To Hear Springsteen Sing ‘Born to Run,’ But Ended Up Crying Over Him Singing Adele…” Stagecoach 2025 turned into a spiritual moment when Bruce Springsteen and Chris Stapleton stunned the crowd with a soul-baring duet of Adele’s “Someone Like You.”

STAGECOACH 2025 SHOCK: BRUCE SPRINGSTEEN & CHRIS STAPLETON SURPRISE FANS WITH AN EMOTIONAL ADELE COVER California – April 2025 – Just when the crowd thought Stagecoach Festival 2025 couldn’t get any bigger, the unthinkable happened: Bruce Springsteen walked onto the main stage during Chris Stapleton’s set — unannounced and to a thunderous roar. But the real shock? They performed a soul-stirring duet of Adele’s “Someone Like You”, reimagined in a raw, Southern blues-meets-classic rock style that no one saw coming….

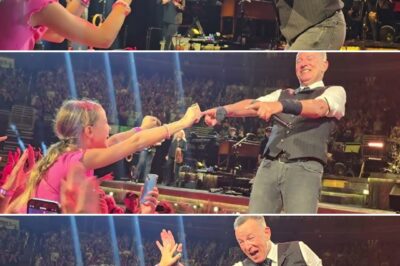

Bruce Springsteen was halfway through The Promised Land when he stopped cold. Not for the lights. Not for the band. But for a little girl—perched high on her father’s shoulders, clapping with perfect rhythm, wearing a tiny, worn-out Born to Run T-shirt.

A Bruce Springsteen concert is always a special occasion, but something truly magical happened at his show last month thanks…

BREAKING NEWS: Ted Nugent Explodes on Social Media, Accusing Bruce Springsteen of “No Longer Being a Man of the Working Class” but Instead “A Millionaire Living in a Mansion, Pretending to Be a Street Hero.”

In the ever-evolving collision between politics, celebrity, and rock music, a new front has opened – and it’s fiery. Conservative…

Man’s Dog Returns After 1 Year Missing, What the Dog Did Next Shocks Him

In a touching display of loyalty and resilience, a beloved family dog returned home after more than a year of…

This rescued pitbull just can’t stop screaming with happiness.

In the aftermath of losing her husband, one woman found unexpected hope and healing in the company of a dog…

German Shepherd Head was Stuck in Metal Gate – What Baby did Next Left Everyone in Tears!

Willow Creek, [Date] — In a heart-stopping scene that unfolded on a quiet morning in the Willow Creek neighborhood, a…

End of content

No more pages to load