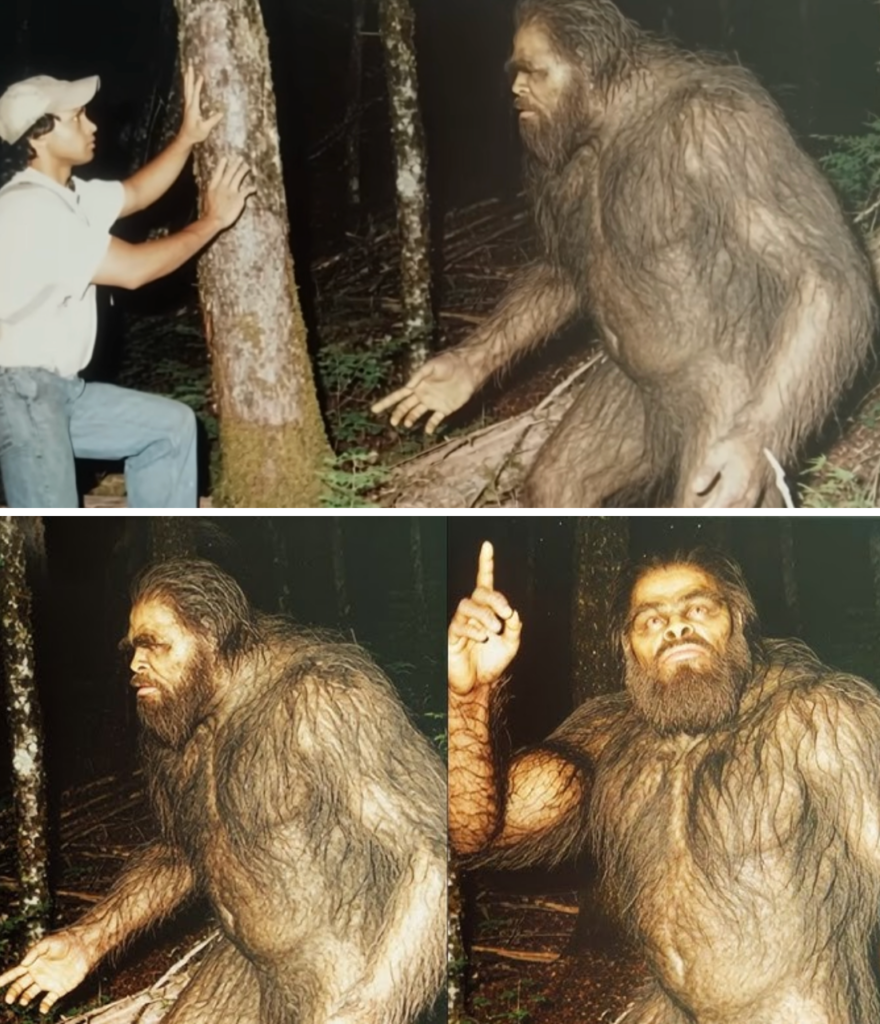

Bigfoot: The Hunter and the Guardian

Bigfoot is real. Not only real, but intelligent—more than I ever imagined. The one I met was kind, thoughtful, and surprisingly human. But he made it clear: his kind is just like us, full of good and bad. Some are gentle; others are monsters. In Northern California, there exists a giant Bigfoot, larger than the one I met, that hunts hikers. But I’m getting ahead of myself. Let me tell you how I met my protector.

I’m an adrenaline junkie. I’ve base jumped off Norwegian cliffs, free-climbed sheer rock faces in Yosemite, surfed twenty-foot waves in Hawaii, cave-dived in pitch-black underwater systems, and spent nights alone in the Australian outback. My friends call me crazy, my family stopped trying to talk sense into me. That feeling—when adrenaline floods your body, every sense sharpens, and you dance on the edge of life and death—that’s what I live for.

But nothing I’ve ever done prepared me for what I encountered on the Devil’s Creek Trail in Northern California.

Devil’s Creek has a reputation. Over forty hikers have disappeared there in the last decade. Their cars were found at the trailhead, their gear scattered in the woods, but the people themselves vanished without a trace. No bodies, no answers. Locals whisper about it in dim bars. Rangers warn you to stick to marked trails, never camp overnight past the third mile marker, always tell someone your plans. But I went there precisely because of the danger. The mystery fascinated me. What was taking these people—bears, accidents, or something else?

It was early October when I drove six hours north to the trailhead. The morning was crisp, the sky a perfect autumn blue. I packed light for a three-day trip: tent, sleeping bag, water filter, dried food, first aid kit, knife, fire starter, flashlight. My pack weighed about forty pounds—comfortable for a multi-day hike.

At the parking lot, I saw two other cars. I was loading my pack when an older couple came down the trail, their expensive gear still pristine. The man asked where I was headed. When I said I planned to go deep into the forest, maybe ten or twelve miles in, their faces changed. They urged me not to go past five miles. They’d only gone three before turning back—something about the forest felt off, too quiet, too empty.

Another hiker overheard and warned me to stick to the marked trails and never camp past the third mile marker. He’d been hiking here for years, but lately, things had changed. People who went too far didn’t always come back.

Their warnings only excited me more. I wanted to see what they were afraid of.

The first few hours were beautiful. Autumn painted the forest gold and red. Sunlight filtered through the canopy. Wildlife was everywhere—squirrels chattering, birds calling, a deer bounding across the trail. I stopped for lunch about six miles in. The trail was less obvious now, more overgrown, but I had my GPS and compass.

By late afternoon, I’d gone about eight miles. I found a clearing by a stream and set up camp. As I cooked dinner and watched the sun sink, I felt satisfied. I’d ignored the warnings and everything was fine.

As darkness fell, I heard something moving in the brush—branches snapping. I yelled, thinking it was a deer or raccoon, and the rustling stopped. I sealed myself in the tent, hung my food bag from a tree, and fell asleep to the sounds of the forest.

At sunrise, I noticed something strange. My backpack, which I’d left by a tree, had been moved—now sitting on the other side of the clearing. Nothing was missing or torn. It had been picked up and set down elsewhere. Bears don’t do that, and raccoons aren’t strong enough. Whatever did this was silent, deliberate, and curious.

I shrugged it off, made breakfast, packed up, and continued deeper into the forest.

The second day, the forest grew denser and darker. Around noon, everything went silent—no birds, no insects, no wind. In the wilderness, silence means a predator is near. My skin crawled. I scanned the forest, but saw nothing.

Then I heard footsteps behind me, matching my pace. I stopped—they stopped. I walked—they walked. I spun around, heart pounding, but saw only empty forest. The footsteps resumed every time I moved. Something was following me, staying just out of sight. I tried hiding behind a boulder, waiting to see what emerged, but nothing happened. When I stepped back onto the trail, the footsteps returned immediately.

This wasn’t an animal. It was something intelligent and patient.

I kept walking, fear growing into dread. By late afternoon, I was genuinely frightened. I stopped in a clearing, hands shaking, feeling watched. Then, in my peripheral vision, I saw something massive moving between the trees—upright, walking on two legs, eight or nine feet tall, covered in dark brown fur. It was a Bigfoot.

We stared at each other. Its eyes were deep, intelligent, aware. It studied me as I studied it. My survival instincts screamed at me to run, so I did—crashing through the forest, branches whipping my face, roots tripping me. I heard the Bigfoot behind me, moving fast, but it never caught up. It stayed thirty or forty yards back, just following.

Eventually, my legs gave out. I tumbled into a ravine, exhausted and gasping for air. I lay there, waiting to die. The Bigfoot approached, stopped ten feet away, and just looked at me. Then, it raised a massive finger to its lips—the universal gesture for silence. It understood gestures. It was trying to communicate.

Its eyes were worried, almost frightened. If this creature was afraid, what could possibly scare it? Then, heavier footsteps approached—the ground vibrating. A larger Bigfoot, ten or eleven feet tall, scarred and mean, with patches of fur missing and huge teeth, was hunting for me.

My protector gently pulled me deeper into the ravine, hiding us behind logs and brush. The larger Bigfoot passed right above us, the smell overwhelming, like rot and musk. I held my breath, praying it wouldn’t see us. It stopped, sniffed the air, growled—a sound of pure menace. My protector trembled beside me, as scared as I was.

After an eternity, the hunter moved on. My protector relaxed and gestured for me to follow. It showed me footprints—massive prints in the mud, nearly twice the size of its own. It showed me claw marks gouged deep into trees, backpacks and jackets hanging from branches—belongings of missing hikers, like grave markers.

It led me to a hidden cave, filled with camping gear, boots, jackets, water bottles—all carefully arranged, like a memorial. Each item represented someone who had never left these woods. The Bigfoot was showing me the danger, the reality: the large one was hunting humans.

For hours, my protector led me through safe paths, avoiding dangerous clearings. Sometimes it disappeared, then reappeared ahead, scouting the way. It showed me more human belongings—a torn tent, a broken stove, a snapped hiking pole. The truth was grim: the hunter had been killing humans for years.

At sunset, we climbed a rocky outcrop and looked over the valley. In the distance, the large Bigfoot dragged something along a game trail. My protector grabbed my shoulder and gestured emphatically: stay away from the valley. It was the hunting ground.

As night fell, the large Bigfoot moved closer. My protector became more urgent, hiding me in a hollow tree trunk, then behind a mossy log. Each time, the hunter passed nearby, searching, frustrated. My protector kept its hand on my shoulder—comforting, reassuring.

Finally, my protector decided we needed to separate. It pointed me toward a cave, then gestured it would lead the hunter away. Before leaving, it placed its hand over my heart, then pointed to its own. The message was clear: we are the same. Both alive, both matter.

It crashed through the forest, making noise, drawing the hunter away. I hid in the cave, listening to the distant sounds of their fight—roaring, trees breaking, the ground shaking. The battle lasted hours. Eventually, the forest went quiet. I didn’t know who had won.

At dawn, the smaller Bigfoot returned—alive, but wounded. Deep scratches, a bleeding bite, matted fur. But it had survived. It gestured for me to follow. We walked for six hours through the safest paths. I was exhausted, blistered, starving, but I kept going.

At last, I saw the trailhead parking lot. My truck was still there. The Bigfoot stopped at the edge of the forest, refusing to come closer to civilization. We stood there, looking at each other one last time. I placed my hand over my heart, then pointed at it. It nodded slowly, understanding. Then it turned and vanished into the woods.

I drove home, shaken and changed forever. I filed a report with the rangers, saying I’d gotten lost. They were skeptical, but I didn’t tell them the truth. Who would believe me?

I researched the Devil’s Creek disappearances. Hundreds of people have vanished in forests across the Pacific Northwest. Most reports of Bigfoot are peaceful, but some describe being hunted, stalked, chased. A few mention aggressive Bigfoot, and even other Bigfoot being afraid.

I believe this is the truth: Bigfoot are real. Most are peaceful, but some are predators—rogues, outcasts, killers. Others, like my protector, try to keep humans safe, understanding the consequences if we discovered the truth.

Three months later, I still have nightmares. I see the hunter’s scarred face, hear its roar. But I also dream of my protector—the intelligent eyes, the gentle hand, the silent gestures. I wonder if it’s still out there, protecting lost hikers.

I’m still an adrenaline junkie, but I’ll never return to Devil’s Creek. Some dangers are too real. Some thrills aren’t worth it.

If you take anything from my story, take this: the woods are deeper and stranger than you think. There are things out there that science doesn’t acknowledge, but they’re real. When you’re alone in the wilderness, you’re not always at the top of the food chain.

Sometimes you survive because something you didn’t know existed decides you’re worth saving. Sometimes the line between monster and guardian is thinner than you ever imagined.

I met both—the hunter and the guardian. And I’m one of the lucky ones who lived to tell about it.

News

He Lived Beside Bigfoot for 30 Years. What It Told Him About Humanity’s Fate…

Elder’s Warning: The Last Witness of the Cascade Bigfoot I am 78 years old now, and for more than four…

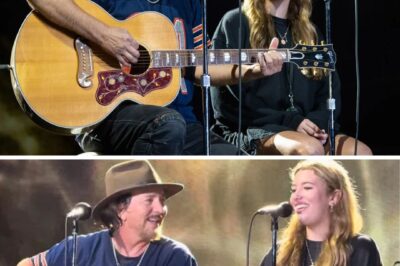

Eddie Vedder Shares the Stage With Daughter Harper for “Last Kiss / Best Day” at Ohana Fest

Eddie Vedder has delivered countless iconic performances, but none hit quite as deeply as the night he shared the stage…

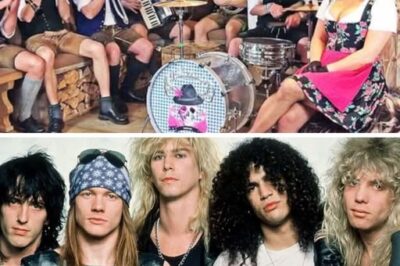

German Polka Group The Heimatdamisch Make Fun Cover Of Sweet Child O’ Mine

A German polka band has taken Guns N’ Roses’ “Sweet Child O’ Mine” and spun it into something wildly unexpected…

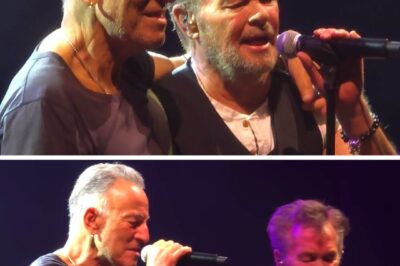

John Mellencamp & Bruce Springsteen Bring the House Down with “Pink Houses” in Newark

John Mellencamp and Bruce Springsteen teamed up for an unforgettable night in Newark, performing “Pink Houses” together and completely electrifying…

“100 YEARS OLD… AND HE STILL WALKED ONSTAGE LIKE HE OWED THE WORLD ONE MORE SMILE.”

“100 YEARS OLD… AND HE STILL WALKED ONSTAGE LIKE HE OWED THE WORLD ONE MORE SMILE.” He stepped onto that…

“THE NIGHT ONE BORING SPEECH MADE AMERICA LAUGH UNTIL IT HURT.”

“THE NIGHT ONE BORING SPEECH MADE AMERICA LAUGH UNTIL IT HURT.” Tim Conway did it again — he took something…

End of content

No more pages to load