Scout: A Debt in the Shadows

When I found the infant creature whimpering behind my woodpile on an October morning in 1992, I made a decision that seemed simple: help it heal, then release it back to the wild. But ten years later, when that same creature returned—now over seven feet tall, staring at me with recognition and something not quite friendly—I realized kindness can create debts you never expect, and some debts come due in ways you never imagine.

My name is Clifford Richardson. I’m 56 years old, living on forty acres in the mountains of Northern California, outside the small town of Weaverville. After retiring from the Forest Service with a bad back, I settled here for peace and isolation—my nearest neighbor four miles away, my days marked by woodcutting, coffee on the propane stove, and a battered Chevy Blazer.

The Encounter

October 12th, 1992. I woke at dawn, made coffee, and stepped outside to check the firewood. Winter comes early here, and I needed to be ready. That’s when I heard it—a sound that didn’t belong. Not an animal I recognized, not anything I could place. A whimper, desperate and afraid.

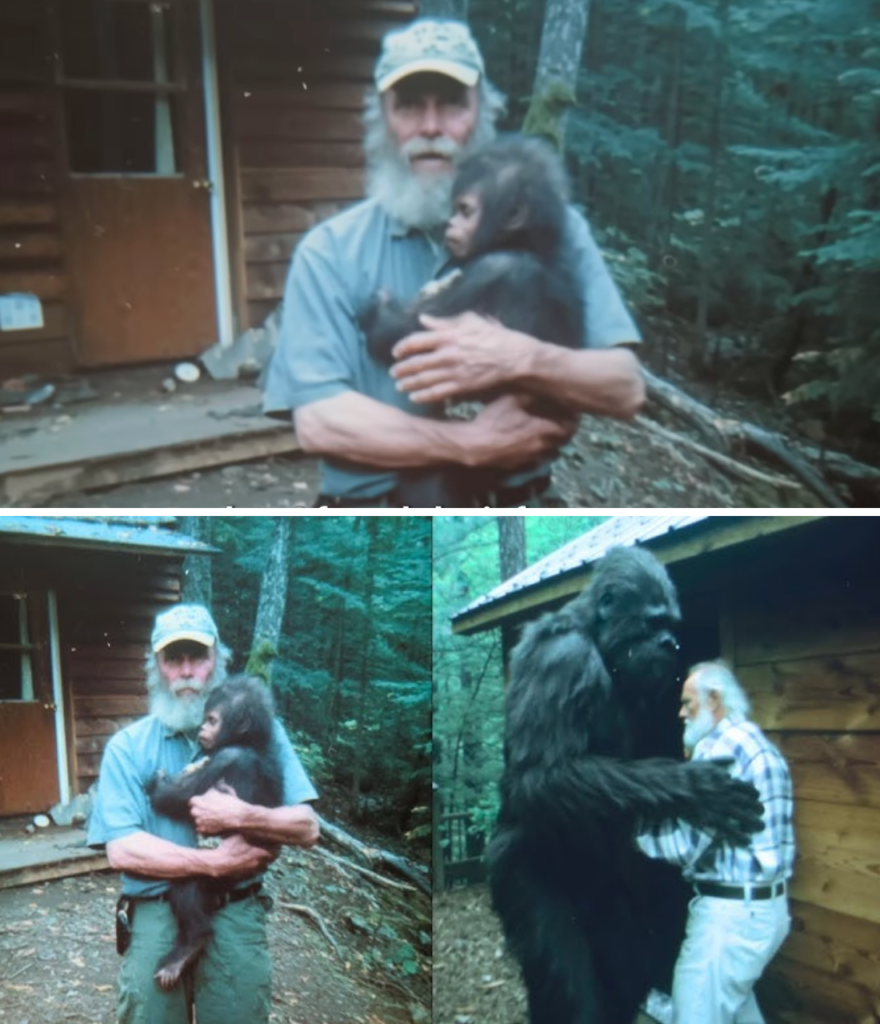

I approached cautiously, expecting a bear cub. But what I found stopped me cold. A creature, maybe two and a half feet tall, covered in reddish-brown fur, matted with pine needles. Upright posture, arms too long, hands—not paws—gripping the wood. The face was flat, wide, with large, dark eyes full of intelligence and terror. Its ankle was twisted, swollen, and it was covered in scratches.

For half a minute, we stared at each other. Every rational part of me said this wasn’t possible—Bigfoot was a legend, a hoax. But this was real, and it was hurt. The creature tried to back away, fell, whimpered again. I knelt beside it, speaking softly as I would to any injured animal. “Easy there. I’m not going to hurt you, but that ankle needs attention.”

It watched me, quieting as I moved closer. Maybe it recognized help; maybe it was simply too injured to flee. I examined the ankle—sprained, not broken. The scratches were deep, infection a risk. “I’m going to splint that ankle and clean those wounds. You let me work, and we’ll figure out what comes next.”

I fetched my Forest Service first aid kit, bandaged the ankle, cleaned the scratches, offered water. The creature accepted the blanket I wrapped around it, let me carry it to my enclosed porch. I tried different foods: meat, bread, fruit. Berries and apples disappeared immediately. Vegetarian, or at least fruit-eating.

Bonding

We settled into a routine. I checked on the creature—Scout, I started calling it—morning and evening, changed the bandages, brought food and water. Scout became less fearful, watched me with curiosity, made sounds that seemed like communication. Scout learned fast, mimicking motions, adapting. This wasn’t instinct—it was intelligence.

By the second week, Scout was walking without a limp. The ankle healed, the scratches faded. It was time to let Scout go. On October 28th, sixteen days after I’d found it, I carried Scout to the forest edge. “You’re healed. You need to be with your own kind.”

Scout reached out and touched my arm—gentle, deliberate. A gesture that needed no translation: thank you. Then Scout turned and vanished into the woods.

Signs

For weeks, I watched the forest edge, hoping for a glimpse, wondering if Scout had found family. Occasionally, I found signs: stones arranged in patterns, pine cones stacked, wild berries left on my woodpile. Scout was out there, surviving, checking in—never close enough to be seen.

Years passed. The signs grew less frequent, then stopped. Life continued: splitting wood, town trips, aging. In 1997, Jimmy Parsons, a local kid, helped with chores. One day, Jimmy came in pale. “I saw something in the forest—big, walking on two legs, covered in dark fur. Not a bear. Seven feet tall, maybe more.” Scout would’ve been five years old, growing. Jimmy never returned after that summer.

By 2000, I found nothing—no signs, no evidence. I tried not to feel abandoned. Scout was an adult now, with its own life.

Return

October 12th, 2002—ten years to the day. I woke to find a deer haunch on my porch, fresh, carefully placed. An offering. That evening, Scout returned, emerging from the trees, now massive—seven and a half feet tall, broad shoulders, fur marked with scars, one ear notched, a finger bent. The eyes were the same: intelligent, dark, fixed on me.

“Scout, you got big,” I said, heart pounding. Scout made a deep sound—not threatening, not friendly, just communicative. Scout gestured toward the cabin, then at me, then drew in the dirt: a small figure, a large figure, the small injured, the large helping, then the small leaving, then returning. Connection, debt, obligation.

“You don’t owe me anything,” I said. But Scout disagreed. More gestures: smaller figures, aggressive postures, Scout positioning itself protectively. Warning—others coming.

The Threat

Engines roared up my access road. Three trucks pulled into my clearing, headlights blazing. Five men emerged, dressed like researchers, carrying cameras, rangefinders, audio equipment. The leader introduced himself: Dr. Marcus Webb, wildlife biologist. They’d tracked Scout for weeks, found my property, and had evidence—photos, thermal images, records of my old veterinary purchases. “Did you treat an injured juvenile cryptid ten years ago?”

I admitted I’d helped an injured animal and released it. Webb and his team wanted cooperation: a research camp, documentation, study. Scout’s reaction was immediate—defensive, aggressive. “Scout isn’t a specimen. You need to leave.”

Webb threatened federal intervention. “One way or another, this individual will be studied. Your cooperation determines how disruptive it is.” The tension was thick. Scout was ready to fight. I negotiated for time—24 hours to consider.

That night, Scout stood guard at my property edge. I stayed awake, trying to plan. Scout approached, concerned for my well-being, offering comfort. We discussed options: cooperate, flee, negotiate. None felt right.

Escalation

At 3 a.m., Scout led me into the woods, showing me footprints—three people, not Webb’s team, had trespassed, searching. Scout found cameras and sensors hidden in the trees. My property was compromised; the evidence was overwhelming.

Next morning, Agent Sarah Menddees from US Fish and Wildlife called. Federal agents would arrive within 48 hours to investigate. My lawyer confirmed: under the Endangered Species Act, my rights were limited. Cooperate, negotiate for minimal intrusion, but resistance was futile.

Scout was terrified—capture meant a fate worse than death. The creature had seen others taken, knew what it meant. Running wasn’t an option; hiding was impossible.

Going Viral

By mid-afternoon, ATVs arrived—three young men, cameras and rifles. They filmed Scout, taunted it, then left, promising to upload the footage. “Millions are going to know Bigfoot is real by tomorrow.” The cryptid community had already spread the news. My property was about to be overrun.

Scout made a decision: pack, prepare, move. I hurried, packing essentials, knowing we had hours before the first wave arrived. But as dusk fell, vehicles converged—seven trucks, fifteen people, cameras, weapons, excitement. Webb was among them, looking desperate.

The crowd surrounded us. Tension mounted. Scout’s posture shifted from defensive to aggressive. Someone fired a rifle—Scout flinched, rage in its eyes. The creature realized it couldn’t protect me, couldn’t fight through the crowd. Instead, Scout created a distraction, running into the forest, drawing everyone away, sacrificing freedom for my escape.

Webb approached. “Can you call it back?” I shook my head. “Scout just sacrificed everything to save me. That’s what your research created.”

I drove away, east into the mountains, setting up camp at a remote forest service clearing. At midnight, Scout found me, exhausted but alive, having evaded the pursuers. “You can’t stay,” I said. “They’ll be searching for both of us.” Scout suggested separation—go deep into the wilderness, stay distant but aware.

The Aftermath

I hated it, but Scout was right. We stayed together until dawn, then parted—Scout into the wild, me toward Reading and anonymity. The aftermath was chaos. Webb’s footage never appeared; amateur videos went viral. My property was swarmed, vandalized, then seized by federal agents. I sold it to the government, signed non-disclosure agreements, moved to a small apartment.

I never saw Scout again. But sometimes, a riverstone would appear on my doorstep, pine cones arranged on my car—small signs that Scout was still out there, still watching, still remembering.

Years have passed. I’m older, more isolated. I lost my home, Scout lost safety. But we gained something too—proof that connection across impossible boundaries is possible, that kindness echoes even when it leads to disaster.

Some nights, I look at the pine cones on my window sill and hope Scout is safe, hidden, at peace. Despite everything, I don’t regret helping. I’d do it again. Because some choices define us, and helping Scout—releasing Scout—trying to protect Scout, was mine.

News

Bob Dylan and Joan Baez closed the show with one last run of Blowin’ In The Wind, their voices weaving together perfectly.

THIS IS HISTORY IN THE MAKING.”Bob Dylan and Joan Baez closed the show with one last run of Blowin’ In…

THIS IS HISTORY IN THE MAKING.

THIS IS HISTORY IN THE MAKING.”Bob Dylan and Joan Baez closed the show with one last run of Blowin’ In…

There’s something different about Christmas music when it comes from a place of real love — not just talent, not just tradition, but the kind of warmth that lives inside a family home.

There’s something different about Christmas music when it comes from a place of real love — not just talent, not…

At the 2025 Rock & Roll Hall of Fame ceremony, a truly unforgettable moment unfolded when pop-punk icon Avril Lavigne

At the 2025 Rock & Roll Hall of Fame ceremony, a truly unforgettable moment unfolded when pop-punk icon Avril Lavigne…

Hollow Man” brings that punchy, unstoppable energy, while “Red, White & Jersey” hits deep with pride and nostalgia for anyone from the Garden State.

MUSIC LEGENDS UNITE!Bon Jovi and Bruce Springsteen are finally joining forces, and it’s electric. “Hollow Man” brings that punchy, unstoppable…

Tim Conway and Harvey Korman: “The Old Sheriff” — A Lesson in Laughter and Timing

Tim Conway and Harvey Korman: “The Old Sheriff” — A Lesson in Laughter and Timing Last night, we revisited one…

End of content

No more pages to load