I’m a wildlife photographer, and last spring I was tracking a wolf pack in Washington’s Cascade Range. After three weeks in the backcountry my GPS died, the batteries drained for no reason, and my phone’s charge vanished overnight. Without navigation I trekked toward a distant ridge, only to hear a low, mechanical hum that didn’t belong in the forest.

Following the sound, I stumbled on a hidden, camouflaged compound tucked into a natural bowl. Three modular buildings, solar panels, generators, and a ten‑foot chain‑link fence topped with razor wire surrounded the site. Armed guards patrolled the perimeter, and white‑coated technicians moved between the structures. Through a telephoto lens I saw people in bio‑hazard suits and a refrigerated truck—nothing on any map, nothing the Forest Service knew about.

The hum was coming from the largest building. Inside, behind a reinforced glass window, sat a massive creature—an eight‑foot‑tall, dark‑furred being that looked like the legendary Bigfoot. It was locked in a bear‑size cage, its shoulders hunched, electrodes and IV lines attached, its eyes dull but unmistakably intelligent. The scientists spoke of “stress levels” and “adjusting the drug cocktail,” treating the creature as a malfunctioning machine rather than a sentient being.

I should have left, but the photographer in me couldn’t walk away. I spent days watching the guards’ shifts, noting blind spots, and learning the routine of a supply truck that arrived every Thursday night. On that night I slipped over the fence, slipped through a propped‑open door, and made my way to the observation room. The cage lock was on a keypad; a ring of keys hanging nearby finally opened it.

The alarm blared. Guards burst in, weapons drawn. In the chaos I tackled one guard, and the creature—now free of its cage—grabbed me and smashed through a wall into a service tunnel. We tumbled down, emerged on the other side of the fence, and ran north toward a river I had scouted earlier.

The river was a raging torrent. We were swept downstream, battered by rocks, fighting hypothermia, but we managed to clash onto a gravel bar as dawn broke. The Bigfoot, though injured, led me through the forest for three more days, teaching me which roots and berries were edible, how to catch fish with bare hands, and where to find shelter. We evaded helicopters and search teams, the river’s current having broken our scent trail.

On the fourth day we reached an ancient, untouched part of the forest. The creature stopped, scented the air, and turned to me with a gentle touch on my cheek—its way of saying goodbye. Then it vanished into the old-growth woods, leaving me alone but alive.

I made my way back to civilization, flagged a logging truck, and told a vague story of getting lost. The photos I had taken—of the facility, the guards, the cage, and the Bigfoot—are still with me, encrypted and hidden. I stopped doing wildlife photography; I now work construction, moving from town to town, always looking over my shoulder.

Would I do it again? Yes. Some choices aren’t really choices at all—they’re a test of who we are. I chose to free a being that should never have been caged, and that makes everything else worth it. The Bigfoot is out there, living free, and that simple fact is enough.

News

“39 YEARS BESIDE HER… AND ONE FINAL SONG HE COULDN’T LET THE WORLD HEAR.”

“39 YEARS BESIDE HER… AND ONE FINAL SONG HE COULDN’T LET THE WORLD HEAR.” They say Toby Keith penned one…

The Red Clay Strays Just Shattered Every Expectation With Their Grit-Soaked, Soul-Packed Take On “Please Come Home For Christmas” That Has Fans Calling Them The Future CMA Legends Live On National TV

“WE’RE NOT JUST SINGING CHRISTMAS, WE’RE BREAKING IT!”The Red Clay Strays Just Shattered Every Expectation With Their Grit-Soaked, Soul-Packed Take…

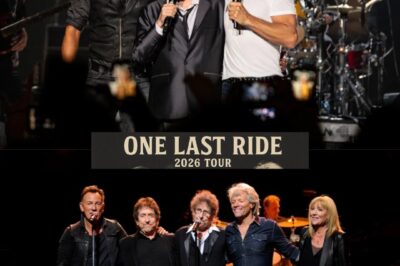

83-Year-Old Paul McCartney Stuns 20,000 Fans in Chicago With a Historic, Soul-Shaking Tour Finale That Proves a Beatle’s Music Can Still Move the World

83 Years Old, 19 Shows, Over 300,000 Fans… And Paul McCartney Just Shattered Chicago on the Tour FinaleNo one could…

She Is The Voice Of Our Shared Conscience And The Heart Of This City

The group performed in a tribute concert for Patti Smith at Carnegie Hall in New York City on Wednesday, March…

Four Titans Of American Rock—bruce Springsteen, Bob Dylan, Jon Bon Jovi, And Patti Scialfa

In an announcement that has left the music world abuzz, four of the most influential figures in American rock have…

“The Moment The Spotlight Hit Him, Everyone Knew Something Was Wrong.”

“The Moment The Spotlight Hit Him, Everyone Knew Something Was Wrong.” What Followed Left Over 40 Million Fans Around The…

End of content

No more pages to load