The Albatross and the Creature Below

In the spring of 1847, the whaling ship Albatross left New Bedford, her crew ready for a long season in the North Atlantic. The voyage began as any other—sails trimmed, casks counted, harpoons sharpened. Captain Bowen led a mixed crew: Reed the first mate, Luis the quiet Azorian harpooner, King the calm boat steerer, Sutter the restless braggart, Daly the silent cooper, and Estabbon the cook who kept the galley warm.

The weather was cold and sharp as we passed Nantucket, taking schools of pilot fish and racks of cod. The work was routine, and the crew settled into the rhythm of watch and rest. But after six days on the banks, the sea began to show its secrets. A gray whale calf surfaced with a ring of circular wounds—smooth, deep, not the torn marks of shark teeth. Luis watched in silence. That night, King pointed out a faint glow moving under the hull, pulsing softly, not plankton but something with form and purpose.

Days later, we found a patch of torn flesh floating on the water, pale and rubbery, with a hard plate embedded in it. Luis called it a beak—larger than any he had seen. The captain ordered careful checks of gear and told me to mark the log. The crew worked quietly, the mood shifting from bravado to caution.

A pod of sperm whales appeared, but the lead whale bore a deep, ringed wound. The pod scattered in fear, leaving behind streaks of oil and shredded tissue. The men grew quiet, focused on repairs and watch orders. On the ninth night, a line came taut against the hull, bearing round scars and a slick, ammonia-smelling film. Reed and Daly inspected it, tying off the damaged hawser and doubling lashings.

Strange bubbles followed us for hours, rising from depths we could not sound. Birds avoided the patch. The captain kept a steady course, but doubled the anchor watch and kept the boats ready to drop. Something moved around us, uncharted and unseen.

On the 11th day, we passed the carcass of a giant squid, torn open, arms missing, head crushed. The captain readied the boats, not to take the carcass, but to prepare for whatever hunted it. That evening, the lead line came up smeared with stinging jelly. Luis watched the water with grim focus.

That night, a line of dim shapes rose and fell behind us—long, smooth mounds, keeping pace with the ship. The captain ordered axes ready and the signal gun loaded. The shapes followed until the watch changed, never breaking formation.

Suddenly, the ship was lifted from below—first the stern, then the quarter, then the bow. Luis dipped a boat hook and brought up strands of clear, burning fluid. The captain ordered a drag out a stern, and when the casks were seized, we chopped the line free. The signal gun flashed, illuminating a pale shape with plates and lines just beneath the surface.

The next day, parallel tracks cut the water, straight as if drawn with a rule. The men lashed and checked everything, order giving hands a place to go when minds circled in fear. Early in the second dog watch, a column of gel and bubbles rose, stinging eyes and skin. The crew cleaned the deck with buckets and scrapers. Sutter avoided the rail, claiming injury.

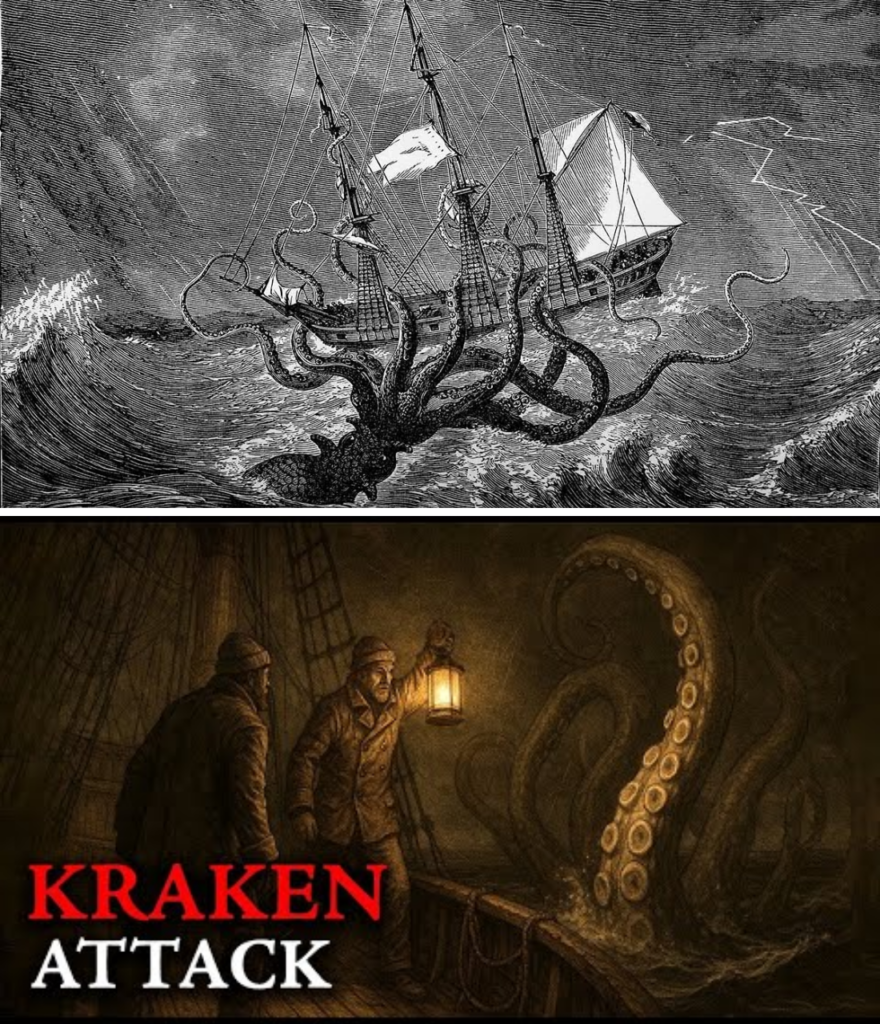

At midnight, the water glowed beneath the hull in shifting bands. The helm grew heavy, the rudder struck hard by something below. Reed saw a pale arm rise and slap the planks—lined with round mouths that gripped the hull. King struck with an ax, and clear fluid sprayed. More limbs rose, searching for purchase. The captain ordered the triworks lit, and the heat drove the arms away from the flames. One arm wrapped the rudder, and King fired a bomb lance. The grip loosened, the arms slid away, and the mounds broke formation.

Dawn showed a deck marked by burns and torn nails. The rudder chains strained and cracked. Sutter argued to turn for home, but the captain insisted on repairs first. At noon, a torn arm drifted past, its mouth still opening and closing. No one cheered. No one believed the danger was over.

That night, the glow returned, circling the hull in bright, pulsing bands. The ship rocked with pushes from below. The bow lifted and slammed down, arms rose and tore at the rigging, one wrapping the foremast and squeezing until it cracked. Men hacked at the limbs, lances and axes flying. Sutter was swept overboard by a sweeping arm, lost to the sea.

The captain ordered the boats cut free. We piled in, rowing into darkness as the Albatross rolled and broke under the assault. The glow faded behind us, but the sea still churned. By dawn, the ship was gone. We had two boats, seven men. Reed kept us together, rationing water and biscuit. The glow followed, sometimes closer, sometimes farther, until a gale split our sail and scattered Reed’s boat.

Four of us remained: King, Daly, Estabbon, and me. By the ninth day, Estabbon raved of the glow beneath us. On the thirteenth morning, a sail appeared—the Margarite out of Nantucket. We were rescued, gaunt and burned. Estabbon died before noon; we gave him to the sea without words.

When I told the captain what we had seen, he wrote that we lost the Albatross to a storm. I did not argue. The sea does not answer. I keep my own record, and when I close my eyes at night, I see the bands of light under the hull and feel the grip on the planks. I do not know if we escaped or were spared. The ocean keeps its secrets.

News

In 1890 Arizona Ranchers Were Hunted by The Thunderbird.

In the scorching summer of 1890, Arizona ranchers faced a terror that soared above their land—a colossal winged beast that…

A Bigfoot Child for a Human Child

Bigfoot in the North Carolina Mountains: A True Encounter and a Tale from the Trailer Park I’ve spent most of…

I Fed a Bigfoot for 40 Years, And I Understand Why It Fears and Avoids Us – Sasquatch Story

The Last Witness: Forty Years With Bigfoot I’ve cared for the same Bigfoot since 1984. What he finally showed me…

“DOLLY, WE HAVE TO DO SOMETHING!”—Vince Gill and Dolly Parton Barefoot on a Porch, Singing a Raw, Trembling Song That Carried Their Friend Through Grief

“DOLLY, WE HAVE TO DO SOMETHING!”Barefoot on her porch, Vince Gill held his guitar, Dolly beside him, and for a…

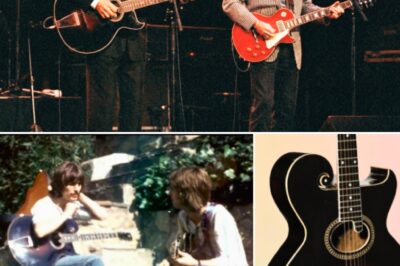

George Harrison and Eric Clapton’s Century-Old “Pattie” Gibson Guitar, Key to Iconic Songs, Heads to Auction After Nearly Hitting $1 Million

George Harrison and Eric Clapton’s 1913 Gibson “Pattie” acoustic guitar is heading to auction, and it’s packed with history. This…

Rick Astley Surprises 50,000 Fans by Jumping onstage with the Foo Fighters, Singing His Iconic Hit “Never Gonna Give You Up” While Tipsy and Jet-Lagged

“RICKROLLED AT A FOO FIGHTERS CONCERT… NOWHERE IS SAFE.”Rick Astley was enjoying a Foo Fighters set at a festival with…

End of content

No more pages to load