The Unseen Genius: How a Rejected Pizza Boy Solved Harvard’s Unsolvable Problem

Most people didn’t notice Daniel Reyes when he walked into Harvard’s Jefferson Hall. That was the point. The security guard at the side door gave him the usual nod, not out of recognition, but out of routine. Daniel delivered for Top Slice Pizza five nights a week. He came through the same door, wore the same red insulated jacket, and carried the same bag, which smelled of oregano and late-night desperation. To them, he was part of the furniture.

But Daniel didn’t walk like the others. His steps were quiet and intentional. He glanced at the room numbers without moving his head, counting his paces as if he were solving something even while walking. In his jacket pocket, folded four times, was a sheet of paper with a math problem—his own version of a love letter to a world that had locked him out. Room 3.16, Department of Mathematics. He stopped at the door and raised his hand to knock, but inside he could hear voices—perhaps a classroom or a faculty seminar. He double-checked the receipt: two pepperoni, one vegetarian, named Monroe.

Daniel had heard that name before, not from TV or TikTok, but from the quiet corners of online math forums buried in threads full of variables, theorems, and late-night desperation. Dr. Adrien Monroe, head of theoretical structures at Harvard, was apparently a man who still ordered pizza during research sprints.

He pushed the door slightly open, and all eyes turned. The room was mid-discussion, filled with professors, postdocs, and a few sharp PhD students. The board was dense with equations, chalk slashing across time and space like a battlefield. Monroe stood near the front, arms folded, gazing at a nested expression on the board as if it had personally betrayed him. He turned slowly toward the interruption.

.

.

.

“Yes?” Daniel said simply, announcing his presence as a pizza delivery boy. The tension broke. Chairs creaked, someone chuckled, and Monroe sighed. “Over there,” he waved toward a table near the wall without looking. “Leave it.”

Daniel nodded and walked in. Ten seconds—that’s all he needed. He placed the boxes down gently, then, slipping it beneath the vegetarian pizza, he tucked the folded paper like it was nothing more than an extra napkin. No one noticed; no one ever did. By the time he reached the hallway again, the door clicked shut behind him.

Back in the room, Monroe lifted the top box absently. He wasn’t hungry, just agitated. But as he reached for a slice, something shifted—a slight edge of white misaligned beneath the liner. He pulled it out, revealing a sheet of graph paper, faint pencil lines, and at the top written in small print, “Re: monictology—possible reduction period. If incorrect, please recycle this.” No name, no credentials, just mathematics.

Five minutes later, Adrien Monroe sat down. He wasn’t eating; he was reading.

Meanwhile, Daniel didn’t go home right away. He rarely did. His studio apartment above the laundromat was less a home and more a sleeping box with mold problems. Instead, he walked two blocks down to the old bench outside the science library and sat, hood pulled up, notebook on his knees. He had three more deliveries that night, but for now, his world was silent. Equations filled his mind—patterns, inversions, a proof half-finished in his bag and another just beginning to form. Numbers were the only things that didn’t lie to him.

He thought back to the first time he had ever seen a chalkboard in person. He was six years old. His mother had cleaned for a university in the city they fled. Daniel would sit on the floor outside the lecture hall, waiting for her shift to end, listening through the crack of the door to voices that spoke in numbers. Later, when they were moved to a shelter in another country, Daniel spent days at public libraries while his mother cleaned houses. He didn’t speak the language well, but numbers had no accent. He found math books, flipped through pages slowly, carefully, copying diagrams into notebooks made from scrap paper.

He had once tried to apply to a community college. He’d aced the placement test, but when the admissions officer asked for transcripts and social security, he stood there, hands empty. The system didn’t know what to do with someone like Daniel Reyes. So now he carried pizza and ideas and a quiet fury at being unseen.

That night, a new thought bloomed on the edge of a half-solved proof—a connection between bounded operators and topological shifts. It danced just out of reach. He scribbled wildly, not caring if the ink bled or if the wind turned the page. Maybe, he thought, what he left under that pizza wasn’t the end. Maybe it was the beginning. For the first time in years, Daniel let himself believe that someone on the other side of the wall, behind the chalkboards, beyond the gate, might finally be listening.

Dr. Adrien Monroe was not easily impressed. In fact, most of his colleagues would have said he was incapable of it. His lectures were notorious. He once dismissed a postdoc’s five-month proof with a single word: “obvious.” He didn’t do small talk. He didn’t do office parties. What he did was logic—cold, efficient, ruthless logic. Which is why the piece of graph paper now flattened on his desk, creased, smudged, and unsigned, was so disturbing.

He hadn’t spoken since the others left. The room hours later was silent except for the faint ticking of the wall clock. Monroe was still sitting there, elbows on the table, eyes fixed on the paper, not moving, not blinking. The lines made sense—not just sense, elegance. There were errors, yes, notational looseness, a minor omission in the third transformation, but those were style issues, not substance. The core insight, the leap, was authentic and new.

Monroe reached slowly for his laptop. He opened a secure file, a working draft he had protected with two layers of encryption. It was his own attempt at resolving the monatic reduction he’d proposed two years ago—a problem even he hadn’t cracked until now. He laid the pizza sheet beside it, compared, matched. It wasn’t a copy; it was an original solution built from a different route, a different mind. But whose?

He flipped the paper over, checked the corners. Nothing. Who just left something like this under a pizza box? Monroe replayed the delivery in his head. The face—a kid, maybe a young adult, Latino, wearing a hood. Didn’t speak much. Certainly not a Harvard student. He would have known, would have remembered. Then the strange line at the top of the paper came back to him: “If incorrect, please recycle this.” Who writes that? Monroe thought. Who sends their work into the void with that kind of humility?

He pulled open his desk drawer and took out the receipt. It listed the order and the delivery service: Top Slice Pizza.

He stood abruptly, grabbed his coat.

Daniel didn’t expect the man in the long gray coat to show up. He was sitting in the back alley behind Top Slice, waiting for his next run, sketching a matrix transformation on a napkin. The kitchen door swung open. Tony, the night manager, poked his head out. “Danny, you’ve got a visitor.”

Daniel looked up. Visitor? Monroe stepped into the light. Daniel blinked.

“You’re the one who delivered to Jefferson Hall tonight?” Monroe asked. Daniel nodded slowly. “Yeah, you left the tip in cash, right?” Monroe didn’t smile. He pulled the sheet of paper from his coat pocket and unfolded it. “This yours?”

Daniel didn’t answer right away. His eyes flicked to the napkin in his hand, then to Monroe’s face, then back. “Maybe.”

“I’m not here to make trouble,” Monroe said. “I just want to know where you learned this.”

Daniel hesitated. “I didn’t,” he said. “It just made sense.”

Monroe’s brow furrowed. “This isn’t guesswork. This is conceptual depth, formal logic.”

Daniel shrugged. “I read a lot, and I remember things. Patterns.”

There was a long silence. Monroe finally said, “Come to my office tomorrow, 10:00 a.m. Bring whatever else you’ve written.”

Daniel’s throat tightened. “I’m not a student.”

“I’m aware.”

“I don’t have any degrees or papers.”

Monroe looked him in the eye. “Then bring your brain. That’s the only credential I care about.”

The next morning, Daniel stood outside Monroe’s office with a folder clutched to his chest. It wasn’t fancy, just a stack of graph paper folded neatly into a recycled manila envelope. Some pages were smudged, others dog-eared, but each held a piece of his mind from the years spent in the margins. He knocked once.

“Come in,” came the voice.

The room was more organized than he expected—sparse, like a monastery of logic. One desk, one chair, a whiteboard that stretched the full wall. And Monroe, seated with the same calm as last night, as though he’d been waiting there since the moment they’d parted.

Daniel stepped in. “You’re early,” Monroe said.

“I like early.”

Monroe gestured to the seat across. “Sit.”

Daniel did, his hands still on the folder. Monroe leaned forward, elbows on his desk. “You said this just made sense to you?”

Daniel nodded.

“Why math?”

He blinked. “Because it doesn’t lie. It doesn’t care if I have a diploma or clean fingernails. It just works.”

Monroe studied him for a long moment, then tapped the folder. “May I?”

Daniel handed it over without a word. The professor opened it slowly, scanned the first page, then the second, then the third. Silence stretched thick and taut. Finally, he said, “You’re not just solving problems. You’re asking new ones.”

Daniel swallowed hard. “Is that bad?”

Monroe smiled faintly. “It’s dangerous to institutions, to people who think understanding belongs to them.”

He flipped to a page marked only by a question and a crude diagram. “Can a graph evolve over non-time conditions? Where did this come from?” Monroe asked.

“A dream, or a fever? I don’t know. It just stayed.”

The professor closed the folder. “I’ve seen minds like yours,” he said. “But they usually come wrapped in degrees and arrogance.”

Daniel looked down.

Monroe tapped the desk. “There’s a symposium next week. Faculty only. Closed door. I want you to come.”

Daniel’s head snapped up. “Me?”

“You won’t speak. You’ll sit. You’ll listen. You’ll take notes. And you’ll learn what this world looks like from inside the wall.”

Daniel hesitated. “They’ll know I don’t belong.”

Monroe stood, walked to the whiteboard. He erased a segment and drew a jagged shape, a boundary, then a small dot just outside it. “Belonging,” he said, “is a boundary others draw so they can stay comfortable.” He tapped the dot. “You’re here.” Then he circled it. “Now you’re part of the map.”

The room was nothing like Daniel expected. Not wood-paneled, not ornate—just functional. White walls, folded chairs, a single projector screen. But the people inside, their presence vibrated. Tenured minds, math royalty—the kind of people who’d published papers before Daniel could write his name in English. He wore his cleanest hoodie and jeans, which still smelled faintly of garlic from last night’s shift. He clutched a spiral notebook like it might protect him.

When Monroe walked in, the others quieted. “Thank you for coming,” he said. “Let’s begin.” No introduction, no announcement of Daniel. He sat in the back, unnamed, unseen, but he listened to the rhythm, to the flow, to how theorems unfolded like arguments between old friends, to how conjectures danced dangerously close to philosophy.

Somewhere, halfway through a presentation on quantum entropy matrices, he felt it—the drop. That sense of falling into a thought so large it eclipsed everything else. He flipped to a fresh page, scribbled something. Not a solution, just a start, but it was enough.

Afterward, he stood alone outside the lecture hall, his brain buzzing, his legs numb. Monroe joined him minutes later. “Well,” the professor asked.

Daniel exhaled. “It’s like watching people build cathedrals out of fog.”

“Good,” Monroe nodded. “Now come to my lab.”

They walked in silence. The halls grew quieter as the crowds thinned. At the end of a narrow corridor, Monroe unlocked a glass door. Inside, Daniel saw chaos. Equations scrolled across glass boards. Open notebooks on every surface. The hum of a server rack in the corner. A world in motion.

“You’ll work here,” Monroe said. Daniel blinked.

“What do you mean?”

“I’ve spoken to the department. You’re unofficial, but I’ve convinced them to grant you research access under my supervision.”

Daniel stepped forward slowly. “But I’m nobody.”

“No,” Monroe said. “You’re a disruption, and that’s exactly what this place needs.”

That night, Daniel didn’t sleep. He sat on the roof of the laundromat, staring at the stars that looked less like lights and more like variables now. In his lap was a single sticky note, one Monroe had left on the desk: “Start anywhere. Just don’t stop.” He opened his notebook and wrote a single sentence: “Belonging isn’t given. It’s drawn.” Below it, a new equation—his own.

Daniel arrived at the lab earlier than Monroe. It was still dark outside, and the building echoed with the kind of silence only academia knew how to produce. He unlocked the glass door using the temporary code Monroe had given him and stepped inside. The air smelled like whiteboard ink and old coffee. He dropped his backpack next to the desk he’d unofficially claimed and sat down, flipping open his notebook to where he left off.

He stared at the line he’d written the night before: “Belonging isn’t given. It’s drawn.” But this morning, it didn’t feel like a statement. It felt like a dare. He got up, uncapped a marker, and turned to the transparent board near the far wall. He didn’t know what the day would bring or who might walk in, so he started anyway: an inequality, then a derivative, then a structure that bent inward on itself like a recursive shadow.

Ten minutes later, he was too deep to notice the sound of the door opening. “You started without me.” Daniel flinched. Monroe stood in the doorway holding two paper cups. “One of these is for you. No sugar, just logic.”

Daniel cracked a smile and took the cup. They didn’t speak again for a while; they just worked—two bodies orbiting ideas. But by mid-morning, something shifted. Monroe leaned back in his chair and said, “I want you to join the workshop this Friday.”

Daniel blinked. “Workshop?”

“Advanced logic under constrained variables. Mostly faculty, some visiting researchers.”

“You want me to present?”

“No. I want you to challenge quietly.”

Daniel hesitated. “Won’t that make them mad?”

Monroe sipped his coffee. “Good.”

Friday arrived fast—too fast. Daniel stood outside the seminar room, watching one researcher after another walk past him in polished shoes and well-practiced confidence. He touched the collar of his button-up shirt; it didn’t fit right. His shoulders had always been narrow. When he entered the room, conversations paused for half a second—not long enough to call it rudeness, just long enough to feel it. He found a seat in the back and kept his notebook on his lap.

Dr. Elaine Barker was leading the session. She was crisp, precise, and brilliant—Monroe’s intellectual rival in every sense. She opened the discussion with a problem on combinatorial constraints under weighted networks. The others leaned forward, eager. Daniel leaned back. He listened. They chased variables, reorganized graphs, proposed assumptions. But something was off. They were working with what they knew, not what they saw.

Daniel raised his hand. The room turned. Barker arched an eyebrow. “Yes?”

“I think you’re treating the redundancy as a flaw,” Daniel said. “But what if it’s the only consistent feature?”

Silence. Someone laughed quietly. Barker didn’t. “Explain.”

Daniel stood, walked to the board, hands trembling slightly. He picked up the marker and drew a counterexample. “If the redundancy is intentional, coded as part of the weight transfer, then the solution space isn’t limited by efficiency. It’s anchored by symmetry.”

He stepped back. The room didn’t applaud, but it didn’t reject him either. Barker stared at the board, then nodded once. “Continue.” And he did.

After the session, Daniel sat alone on the stone steps outside the mathematics building. The wind was sharp, but he didn’t mind; it cleared his head. He didn’t hear footsteps until they were next to him. “Do you always challenge people who can end your career before it starts?” It was Barker. Her tone was even—not hostile, not kind.

Daniel didn’t answer right away. “I wasn’t trying to win,” he said finally. “I just couldn’t pretend not to see it.”

She studied him for a long moment. Then she reached into her coat and handed him a folded piece of paper. “Next time, bring this. It’s an invitation to the winter colloquium.”

Daniel stared at it. “I’m not faculty.”

“No,” she said. “But you might be the only one who asks questions worth answering.” Then she walked away.

That night, Daniel returned to the lab. The building was quiet again, and the city outside hummed like a lullaby. He turned on the desk lamp and sat down at the glass wall. For a long time, he stared at the untouched surface. Then he wrote three words: “Proof of existence.” Underneath it, he built a problem—not to solve it, but to see if it could live. Because for the first time, he wasn’t just solving for X; he was solving for Daniel.

The winter colloquium wasn’t listed on the university calendar. There were no flyers, no emails, no public invites. It was one of those traditions passed quietly between tenured hands and whispered in chalk-scented hallways—an annual gathering of the department’s elite to discuss the ideas they didn’t yet want the world to know they were thinking.

Daniel almost didn’t go. Even with Barker’s invitation in hand, he’d folded and unfolded the paper six times that morning, wondering what would happen if he just didn’t show up. What would they do? Revoke the invitation? Pretend he’d never been seen? But then he remembered what Monroe said: “Disrupt gently.”

So he went. Room 7.24 was tucked behind a service stairwell, accessible only by a corridor so narrow it looked like a maintenance passage. Daniel arrived five minutes early and stood outside the door, breathing slowly. He could hear the low murmur of voices inside—measured, deliberate, confident. He stepped in.

The room was warm, dimly lit by recessed lights that made the chalkboards glow like ancient relics. Roughly twenty people sat in a loose circle—some cross-legged, some perched on stools. No name tags, no podium, just minds. Monroe gave him a short nod as he entered. Barker didn’t look up. Daniel took the one remaining seat in the corner, keeping his notebook on his knees.

A man with silver hair and a voice like glass breaking cleared his throat. “Tonight’s prompt: Is the pursuit of elegance in a proof a distraction or a necessity?” A few chuckles, but no one laughed long because they all knew it was a real question.

Barker spoke first. “Elegance matters because it reflects understanding. Complexity without clarity is camouflage.”

Someone countered, “But real problems are messy. Seeking elegance too early means we miss the truth—trying to dress it up.” Daniel didn’t speak—not yet. But he listened carefully. As the debate moved, the chalkboard filled slowly: definitions, diagrams, counterexamples, lines that started strong, then trailed into silence.

And that’s when Daniel saw it—a pattern between the diagrams, not in what they wrote, but in what they avoided. A silence shaped like structure. He raised his hand. The conversation paused. Monroe gestured. “Go ahead.”

Daniel stood slowly. “You’re treating elegance like a style, but maybe it’s a consequence.” He walked to the board and circled three separate symbols. “These look different, but they collapse under the same constraint if you reverse the order of dependency.”

He adjusted the final diagram. “It’s not that we chase beauty; it’s that real structure becomes beautiful when it’s honest.” Silence—not the awkward kind, the listening kind. Then Barker stood, walked to the board, and added one line beneath his diagram. “You’re right,” she said. “That was all.”

Afterward, Monroe found him outside, sitting on a bench with his jacket zipped to the neck. “Do you know how rare it is for someone to speak in that room and not get steamrolled?”

Daniel looked down. “I wasn’t sure I should.”

“You didn’t speak to impress,” Monroe said. “You spoke because you had something real to say. That’s what they remember.”

Daniel didn’t reply. Monroe handed him a thin booklet. “This is a draft paper, something Barker and I are co-authoring. I’d like you to annotate it.”

Daniel blinked. “Me?”

“You see through noise. That’s rare. Don’t waste it second-guessing yourself.”

Daniel took the booklet. He didn’t open it—not yet. He just held it, fingers pressed against the spine like it was a hinge to another world.

Later that night, back in the lab, Daniel opened his notebook and wrote just two lines: “I didn’t belong. And then I did.” Below it, he drew a structure with no boundary, no edges—just points converging, a topology of acceptance. The proof wasn’t finished, but the direction was perfectly clear.

Daniel didn’t sleep the night after the colloquium—not from adrenaline, not even from fear. It was something else—something subtler, quieter, more disruptive. Possibility. He lay on the narrow mattress in his studio above the laundromat, fingers laced behind his head, eyes open to the ceiling’s peeling paint. The draft paper Monroe had handed him sat on his chest, unopened. He hadn’t dared touch it yet. It wasn’t intimidation; it was reverence.

At 4:13 a.m., he finally sat up, opened it, and began to read. The paper was dense, brilliant, but dense. It proposed a new framework for mapping high-dimensional logical flows through combinatorial space. Most of the department would have taken weeks to parse it. Daniel devoured it before sunrise, and he found something. It wasn’t an error; it was an absence—a space where a variable should have been defined, a transition that jumped too cleanly. He circled the line, then added a question mark, then sat back and stared.

The next morning, he arrived at the lab early, paper tucked beneath his arm. Monroe was already there. So was Barker. Daniel hesitated at the threshold. They were arguing softly, but unmistakably.

“No, Adrien, you skipped it. It’s too tidy.”

“I simplified for the sake of clarity.”

“And in doing so, you removed the teeth.”

Daniel cleared his throat. “Sorry, I can come back.”

Barker looked over. Her expression was unreadable. “Come in. We need your eyes.”

Monroe raised an eyebrow. “Already?”

Daniel stepped inside. “I think there’s a missing variable.”

Monroe folded his arms. “Show me.”

Daniel laid the paper on the desk and pointed. “This transition between boundary set delta and upper recursion. It skips something. You define the endpoint but not the shift.”

Barker leaned in, then looked at Monroe. “He’s right.” Monroe stared at the page, then gave the smallest, sharpest smile Daniel had ever seen on him. “Then let’s fix it.”

They worked through the morning. Daniel sat between two of the sharpest minds in American mathematics—not as a student, not as a guest, but as a collaborator. He didn’t speak often, but when he did, they listened. At one point, Monroe passed him a marker. “Go ahead, take the board.”

Daniel froze, then stood. For the next 40 minutes, he wrote, adjusted, erased, and rewrote. When he stepped back, the equation had evolved—not cleaner, not simpler, but truer.

Barker stepped forward. “This changes the whole conclusion.”

“Yes,” Monroe said. “And it’s better.”

By late afternoon, the lab door opened again. Dean Evelyn Marshall entered, heels clicking like punctuation. “I hear there’s been progress,” she said.

Monroe gestured to the board. “There’s been evolution.”

She studied the writing, then turned to Daniel. “And who is the author of the change?”

Monroe didn’t answer. Daniel did. “No one. It came from the problem.”

She narrowed her eyes. “Modest, but unhelpful.”

Barker stepped in. “He’s not being modest. He’s being honest.”

Dean Marshall paused, then said, “I want this version published with full credit.”

“To who?” Barker asked.

Marshall looked at Daniel. “That depends. Are you ready to be named?”

Daniel looked at the board, at the proof, at the line he’d drawn that curved just slightly off the axis—the imperfection that had made the difference. He took a breath. “Yes.”

That night, Daniel walked to the Charles River and stood at the water’s edge. The air was cold; his jacket wasn’t warm enough, but his blood was still humming. Not from pride, from clarity. He opened his notebook. On a fresh page, he wrote, “Sometimes the missing variable isn’t in the math; it’s in the mirror.” He drew a small shape beside it—not a theorem, not a model, just a door. And this time, it was open.

The article came out on a Tuesday. Daniel hadn’t known it was coming. Monroe hadn’t mentioned it. Barker hadn’t hinted. And yet there it was, published in the Journal of Advanced Mathematical Structures—a peer-reviewed piece titled “Reframing Recursive Dependencies in Boundary Transformations” by Adrien Monroe, Elaine Barker, and Daniel Reed—his name on paper in ink. He stared at the screen until the letters blurred.

The email accompanying the article was short: “Congratulations, you are officially published. Get some air.” Monroe.

Daniel closed his laptop and stood, but he didn’t go outside—not yet. He paced, then sat, then stood again. He didn’t know what to feel. Pride didn’t feel big enough. Fear wasn’t exactly right either. The right word was wait. This wasn’t just a name; it was a declaration. And declarations had consequences.

At the café near Harvard Yard, Maya was waiting. She saw him approach through the glass and waved him inside. “You look like you’ve seen a ghost.”

“I think I became one.”

She tilted her head. “Sit. Talk.”

He did. He told her everything—the paper, the footnote that Monroe added, crediting Daniel for the structural pivot, the final edits. “You’re going to get attention now,” Maya said. “Like real attention.”

“I don’t want attention.”

“Too late.”

He didn’t respond.

Maya leaned forward. “What scares you more? That they’ll come asking who you are or that you’ll have to answer?”

He stared at her, then at the window. “Both.”

The next day, a stranger approached him outside the math building—early 40s, sharp suit, too polished to belong on campus. “You’re Daniel Reed?”

Daniel nodded cautiously.

“I represent the Lynwood Fellowship. We’d like to sponsor your research.”

Daniel blinked. “I don’t have a research track.”

“You do now.” He handed Daniel a card. It glittered. That week, the offers kept coming: emails, voicemails, meeting requests, photos of whiteboards asking if he’d weigh in, invitations to speak, to teach, to consult.

Monroe noticed. “You wanted to solve equations,” he said one afternoon. “Now you’re the variable in everyone else’s.”

“I don’t want to be anyone’s variable.”

“Then become your own function.”

Daniel frowned. “That’s not math.”

“It’s identity.”

The pressure changed the air. Even the lab felt different. People knocked before entering. Barker deferred more in meetings. Even Monroe seemed to pause when addressing the group, as if choosing his words more carefully. Daniel hated it. He wasn’t here for reverence; he was here to work.

So, he disappeared for two days. No laboratory, no meetings, no inbox—just the second floor of the public library near the window with the dusty blinds. He scribbled in his notebook until the margins bled. What was he trying to find? Not another paper, not another proof. He was trying to find himself again—the Daniel who had once solved problems in silence, the one who whispered to chalkboards, not to crowds.

On the third morning, Monroe found him there. He didn’t scold; he just sat. “Names are useful until they’re not,” Daniel looked up.

“Your name is on a paper now,” Monroe said. “But don’t confuse that with your purpose.”

“I didn’t want this kind of noise.”

“I know, but sometimes the noise tells you what signal still needs to be found.”

Daniel looked down at his notebook at the half-finished proof. “I thought I’d feel different.”

“You are different,” Monroe said. “You’ve stepped into the equation. Now it’s your job to decide how far you carry it.”

Daniel closed the notebook. “I want to go back to the lab.”

“Then bring that piece with you. Whatever you’re building in there doesn’t belong to the world yet, but it belongs somewhere.”

Daniel nodded. And for the first time in days, he smiled—not for the paper, not for the name, but for the silence in his head. The silence that always came before something true—the next chapter, the real one.

By the time winter set its full weight upon Cambridge, Daniel had begun to construct something he hadn’t told anyone about—not Monroe, not Barker, not even Maya. It wasn’t a paper; it wasn’t a problem. It was a question. He called it the function of quiet. It started as a scribble in the corner of his notebook during a particularly loud seminar, one where visiting scholars debated aesthetics over rigor and lost track of both. But the idea stayed with him. What if the most profound patterns aren’t the ones shouted across chalkboards but whispered beneath them?

He started collecting cases—historic problems that were overlooked for decades because they didn’t look spectacular, theorems proven in notebooks no one read, mathematicians who died unknown but left behind insights embedded like fossils inside unpublished drafts. Daniel began spending more nights in the archive building than in the lab. One night, Maya caught him there.

“You missed Monroe’s open proof challenge,” she said, dropping her backpack beside his chair.

“I wasn’t ready to prove anything new.”

She sat beside him. “Then what are you doing here?”

“Trying to prove something old deserved more time.”

She raised an eyebrow. “You’re chasing ghosts now.”

He smiled faintly. “Maybe. Or maybe I’m chasing the people no one else remembered.”

What began as curiosity became obsession. He created a file, obscura.doc. It contained more than 30 unsolved or dismissed patterns, each tied to a name most scholars would never recognize. One in particular, a 1937 equation from a Syrian teacher named Samir Aliad, stood out. It resembled a recursive geometric fold but collapsed unpredictably past a certain threshold.

Daniel couldn’t let it go. He worked on it every night on his floor, in the café, between classes, and then it clicked. The problem wasn’t the math; it was the language. The original notation had been mistranslated. What looked like a constraint was a condition. The moment he flipped it, the pattern unfolded with an elegance that made Daniel lean back in his chair, stunned. It wasn’t just a solution; it was a key to a conceptual space no one had seen.

When he showed Monroe, the man stared at the board for a long time, then finally said, “Where did this come from?”

“Syria.”

Monroe blinked. “You’re telling me you just corrected a 90-year oversight?”

“Yeah. I listened to it differently.”

Monroe looked away. “We build towers, Daniel, but sometimes we forget to check the foundations.”

Daniel nodded. This one was still solid—just buried.

The department wanted to publish again. They wanted interviews. They wanted to host a symposium titled “Quiet Math, Forgotten Minds.” But Daniel said no. He didn’t want the spotlight; he wanted a wall. He got permission to use the lower seminar room in Jefferson Hall, room B12—a space so rarely used that it still smelled faintly of chalk and old varnish. There, he started a weekly series. No speakers, no professors, no press—just students. One rule: bring a problem no one claps for.

He called it the Midnight Function. The first week, three students came. The second week, ten. By week four, the room was full. They didn’t sit in rows; they didn’t raise hands. They gathered in circles. Some solved together. Some just listened. And Daniel, he sat quietly. He didn’t lead; he learned. Because some functions aren’t meant to dominate; they’re meant to connect. And in that connection, Daniel found something he hadn’t expected: peace.

On the last page of his notebook, Daniel wrote a line: “Let the world find the loud answers. I’ll be busy asking the quiet questions.” The proof wasn’t finished, but the direction was perfectly clear.

The spring after Daniel returned from Syria was quiet—quiet in the way only meaningful things are. No press, no ceremonies, just a boy back where he started, walking through the halls of Jefferson Hall with something new in his posture. Not pride, not fame—presence.

He resumed the Midnight Function, but this time he opened the room earlier—10:00 p.m., not midnight—and he left the door propped open with the chalk he had brought back from Aleppo. One evening, Monroe stopped by. He didn’t speak; he just sat on the back bench, hands folded, watching students—some freshmen, some grad students—argue over an abandoned equation from 1956.

Daniel looked back, nodded once, then turned to help a girl struggling with a recursive loop. That night, Monroe left behind his notebook. On the inside cover, he’d written, “It’s not about who solves the problem. It’s about who dares to look again.” Daniel smiled when he found it.

Weeks passed. The group grew—not exponentially, but steadily. One night, a boy with a stutter asked if he could teach a concept he’d been working on alone. Daniel said, “Only if you bring the mistakes, too.”

The boy blinked. “Why?”

“Because mistakes are how the room breathes.”

By the end of the semester, the Midnight Function had become something else—a network, a shared pulse. It spread quietly like the best things do. A professor at Princeton emailed Daniel, asking permission to start a chapter; then one from Kyoto, then Cape Town, then Lima. Daniel never trademarked it, never branded it. He just said, “Make sure the door stays unlocked.”

Years later, Daniel would be invited to return to Harvard as a lecturer. He refused the spotlight post but accepted one condition: that room B12 never be reassigned. It became the only classroom at Harvard not tied to a department. It had no syllabus, no professor, no grades, but it was always full. Sometimes Daniel still sat in the back. No one recognized him. He preferred it that way because for all the accolades, all the headlines, all the equations he’d helped untangle, what he cared most about was the sound of chalk and the silence that followed when someone finally saw the problem clearly.

News

Unthinkable Horror: Dr. Finn’s Shocking Betrayal! He Secretly Terminates Luna’s Pregnancy Without Consent! 😱💥

The Bold and the Beautiful: A Shocking Betrayal In the glamorous world of Los Angeles, where love and betrayal intertwine,…

Shocking Betrayal: Bill Sends Pregnant Luna to Prison! Secrets and Alliances Threaten the Spencer Dynasty! 🌪️👶

The Bold and the Beautiful: A Family Torn Apart In the glamorous world of Los Angeles, where love and betrayal…

Delivery Man Solves $100M Puzzle in Minutes — CEO’s Shocked Reaction Leaves Everyone Speechless!

Love in the Boardroom: The Story of Gabrielle and Trevor In the high-stakes world of technology, the boardroom of Phoenix…

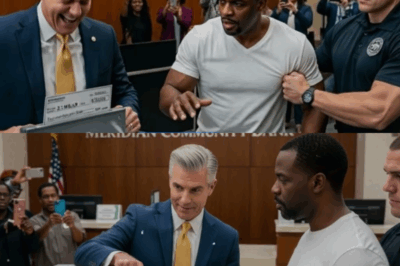

Black CEO Stuns Bank After Manager Shreds His Check in Front of Everyone!

The Reckoning at First National Bank In a bustling lobby of the First National Bank of Chicago, an ordinary day…

Heartfelt Farewell: Erika Kirk Delivers Emotional Tribute at Charlie Kirk’s Funeral

Erika Kirk’s Heartfelt Tribute to Charlie Kirk at His Funeral In a deeply emotional ceremony, Erika Kirk, the widow of…

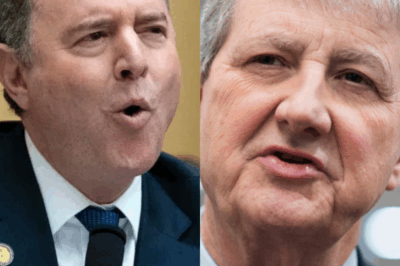

Adam Schiff’s Bold Move to Outsmart Senator John Kennedy Backfires, Leaving Everyone Speechless!

Adam Schiff vs. John Kennedy: The Epic Showdown That Left America Speechless In a dramatic Senate hearing that has captivated…

End of content

No more pages to load