Chapter 1: The Witness

The obsidian black of the car was a stark, wealthy smear against the relentless white of the snowstorm. Inside the climate-controlled cabin, Arthur Harrington, CEO of Harrington Global and a man whose net worth could rival a small nation’s GDP, was engrossed in a quarterly report on his tablet. He hated driving himself, preferring the anonymity of being chauffeured, but his driver had called in sick with the flu, leaving Arthur piloting the armored Mercedes S-Class through the rapidly accumulating snow.

.

.

.

He was impatient, annoyed by the delay the weather caused, and utterly focused on the $30 million bid he needed to finalize before midnight.

Then, a flicker.

The headlights cut through the swirling curtain of white, illuminating the edge of the abandoned park. Arthur’s eyes, trained to spot anomalies in market trends and accounting statements, snagged on a movement that was deeply, terrifyingly out of place.

He saw the small figure fall. Not stumble, but collapse entirely, vanishing into the fresh, deep snow bank beside the wrought-iron park fence.

Arthur frowned, momentarily tearing his gaze from the glowing screen. A dog? No. Too tall, too human. He pressed the brake, the sophisticated anti-lock system whispering as the car slid to a gentle halt. He wasn’t known for his humanitarian impulses. Time was money, and stopping for a minor incident was a luxury Arthur rarely afforded himself. It’s probably just a kid roughhousing, he thought, reaching for his tablet again.

But then the figure struggled back up. Slow, agonizingly slow. And what Arthur saw next, under the sharp, cruel beam of the Mercedes’ headlamps, caused a cold deeper than the December air to seize his chest.

It was a boy. A child, surely no more than seven years old, dressed in clothes that looked like rags, soaked through and clinging to his impossibly thin frame. His face, when he finally turned toward the car’s light, was blue-tinged and caked with frost. But it wasn’t the boy’s hypothermia that made Arthur’s hand freeze on the ignition.

It was the burden he carried.

Clutched to the boy’s chest, swaddled in what appeared to be strips of dirty linen and worn blankets, were not one, but three distinct bundles. Three lumps that were clearly too small, too still, to be anything but infants.

Arthur Harrington, a man who had faced down hostile takeovers, survived political intrigue, and never shed a tear at the sight of a competitor’s ruin, suddenly felt a profound, paralyzing shock. The sight was primitive, almost biblical—a small, desperate shepherd leading three impossibly fragile lambs through a killing storm.

The boy took another staggering step, his whole body shaking, fueled only by a desperate, silent promise.

“Jesus,” Arthur muttered, the word escaping on a shaky exhale. He didn’t question it. He didn’t think about the bid, the time, or the cold. He hit the hazard lights and threw open the heavy door of the Mercedes, the temperature plummeting instantly in the cabin.

“Hey! Stop!” he yelled, his voice rough against the howl of the wind.

The boy flinched but did not stop. His eyes, huge and terrified, darted toward the towering, expensive figure emerging from the car. He tried to speed up, a futile burst of energy that lasted barely a second before his legs gave way again. This time, he didn’t just fall; he tumbled, rolling slightly, but keeping his death grip on the precious bundles.

Arthur sprinted through the gathering snow, his $3,000 Italian leather shoes sinking into the icy sludge. He reached the boy, dropping to his knees without caring that the snow soaked his Savile Row trousers.

“Don’t move. I’m here. I’m helping you,” Arthur commanded, his hands moving automatically to the boy’s arms.

The boy whimpered, a frightened, animal sound, trying to pull the bundles closer. “No! Mine! You can’t take them!”

“I won’t take them, I swear,” Arthur said, the urgency in his voice cutting through the panic. “But they are freezing. You are freezing. We need to get you into the car right now.”

He carefully peeled the boy’s numb fingers away from one of the bundles. It was heavier than he expected. He quickly flipped back the edge of the blanket.

The sight of the baby’s face—blue lips, skin like parchment, completely unresponsive—made the air rush out of Arthur’s lungs. The child was barely breathing. This wasn’t just a crisis; it was an emergency measured in seconds.

Arthur, who hadn’t held a child in forty years, scooped up the first infant gently but swiftly, cradling the tiny, ice-cold bundle in the crook of his arm. He then pulled the boy to his feet, ignoring the child’s weak protests.

“You hold the other two! Come on!”

He half-carried, half-dragged the seven-year-old back to the S-Class. He opened the rear door, where the heated seats were already humming. He gently placed the first infant on the heated leather, then helped the boy clamber in. The boy, exhausted and defeated, slumped against the door, still clutching the remaining two babies tightly.

Arthur reached for his phone, his mind finally catching up to the severity of the situation. He bypassed 911. He didn’t have time for dispatchers and local ambulances. He called Dr. Helen Vance, the chief of pediatric surgery at the private hospital he endowed.

“Helen, it’s Arthur. I have four emergencies. Three newborns and a child, severe hypothermia. I’m three minutes from your ER entrance. Prep a triage team, stat. I want every single available incubator ready. Don’t call the police. Don’t call social services. Just save them.”

He slammed the phone down. He then looked at the boy—who was staring at him with a mix of fear and fierce protectiveness—and the three silent, pale bundles between them. The sheer, impossible courage of the child, enduring the blizzard to save three others, made Arthur feel a burning shame for his own small, wealthy worries.

He put the car into drive, peeling away from the curb. The fate of four forgotten souls now rested entirely on the speed of his car and the resources of his fortune. The meeting was forgotten. The market bid was irrelevant. The real work—the work that mattered—had just begun.

News

FORRESTER WAR! Eric Forrester Shocks Ridge By Launching Rival Fashion House—The Ultimate Betrayal?

👑 The Founder’s Fury: Eric’s Rebellion and the Dawn of House Élan 👑 The executive office at Forrester Creations, the…

The Bold and the Beautiful: Douglas Back Just in Time! Forrester Heir Cheers On ‘Lope’ Nuptials

💍 The Golden Hour: Hope, Liam, and the Return of Douglas The Forrester Creations design office, usually a kaleidoscope of…

REMY PRYCE SHOCKER: Deke Sharpe’s Final Rejection Sends Remy Over the Edge—New Psycho Villain?

💔 The Precipice of Madness: Remy’s Descent into Deke’s Shadow 💔 The silence in the small, rented apartment was a…

Alone and Acting? B&B Villainess Caught in Mysterious Performance After Dosing Her Victim!

🎭 B&B’s Secret: The Ultimate Deception The Echo Chamber of Lies The Aspen retreat—a secluded, glass-walled cabin nestled deep in…

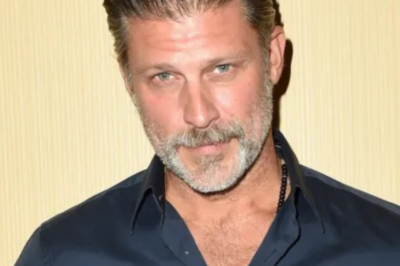

Beyond the Gates Cast Twist! Beloved Soap Vet Greg Vaughan Confirmed as New ‘Hot Male’ Addition!

🤩 Soap Shock! Beyond the Gates Snags a ‘Hot Male’ — And It’s [Insert Drum Roll]… Greg Vaughan! The Mystery…

Brooke & Ridge: B&B’s Reigning Royalty or Just a Re-run? The ‘Super Couple’ Debate!

👑 Brooke & Ridge: Are They B&B’s Ultimate ‘Super Couple’ or Just Super Dramatic? A Deep Dive into the ‘Bridge’…

End of content

No more pages to load