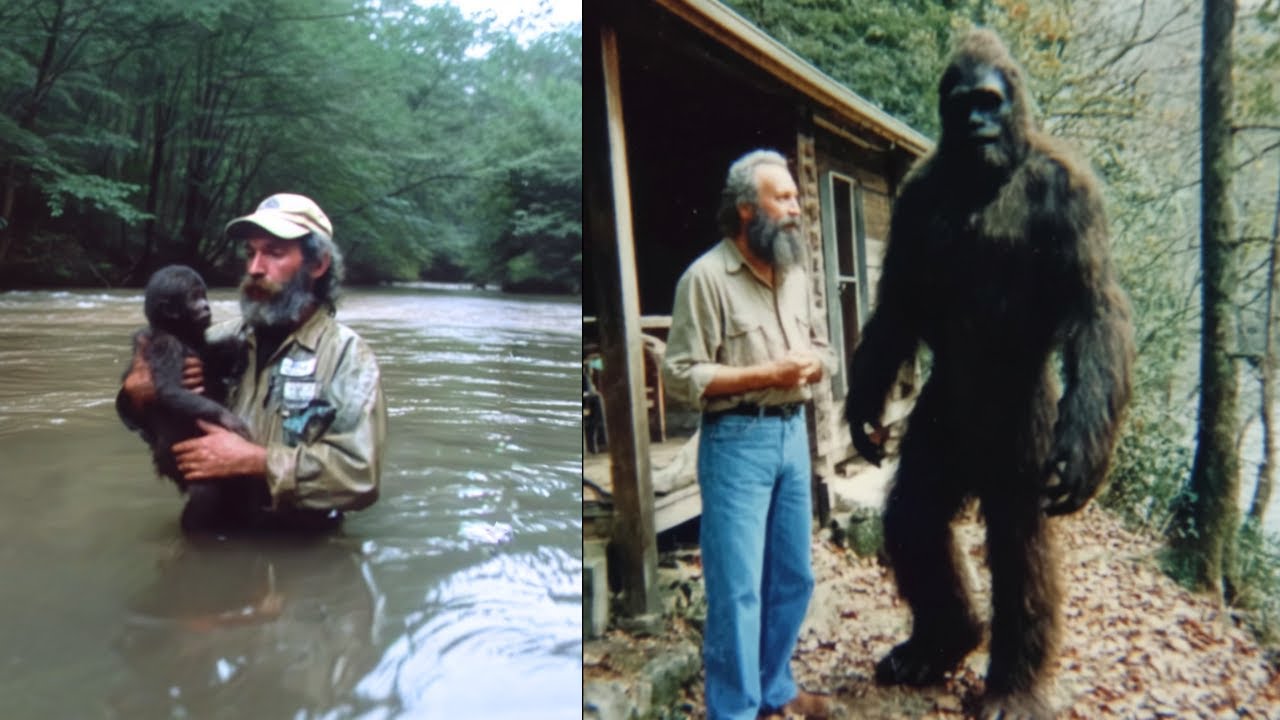

He Saved a Baby Bigfoot From the River… The Next Day the Father Showed Up

The Father in the Trees

I thought I was saving a baby monkey from drowning that afternoon in June.

But when I pulled a small, soaking creature from the rushing water and looked into its dark, impossibly aware eyes, something in my gut told me I’d just encountered something that shouldn’t exist.

The feeling lasted only a moment before I pushed it away, choosing to believe the rational explanation. I had no idea that decision—to save that creature and then let it go—would bring something to my doorstep that would change everything I thought I knew about the forests surrounding my home.

My name is Gary Hawkins, and I’m 45 years old. I’ve been living in a small house on the edge of the Gifford Pinchot National Forest in Washington State for the past 12 years, ever since my wife Linda passed and I needed somewhere quiet to rebuild my life.

It’s June 1994. I work as a forestry consultant, which means I spend most of my time walking through these woods, assessing timber, checking for disease, and generally being left alone.

That suits me just fine.

My property sits on five acres, about two miles from the nearest neighbor, with the Cispus River running along the eastern boundary. It’s a beautiful spot, peaceful most of the time, with the constant sound of rushing water and wind through the Douglas firs. I’ve got a small workshop where I do woodworking in my spare time, a Ford F-250 parked under a rusting carport, and enough solitude to keep the memories at bay most days.

The house is modest. Two bedrooms, one bathroom, a kitchen with appliances from the ’70s, and a living room with a wood-burning stove that keeps me warm through the harsh winters. There’s a telephone on the wall in the kitchen, a TV with rabbit-ear antennas that pick up three channels when the weather cooperates, and a radio usually tuned to the local country station.

It’s a simple life. It was enough.

Until the afternoon I pulled something impossible out of the river.

The Little One in the Water

That Tuesday afternoon, I’d been walking along the river, checking some cedar trees upstream for bark beetle damage. The Cispus was running high from late spring snowmelt, the current fast and dangerous. Every year someone went under in that river, thinking they could wade across or fish from slick rocks.

I’d been warned plenty about getting too close during this time of year.

I was about half a mile from my property when I heard it—a high‑pitched sound, almost like a child crying, coming from the direction of the water. My first thought was an injured fawn. It happens. They slip on the rocks or get separated from their mothers.

But there was something about that sound, a tone that cut straight through my chest and pulled me faster toward the riverbank.

When I broke through the undergrowth, I saw it.

Something small in the water, being swept downstream by the current. Dark fur. Tiny arms flailing. It was clearly struggling.

My brain stamped a label on it—baby animal—and after that instinct took over. I kicked off my boots and waded in.

The water was shockingly cold, snowpack cold, and the current was stronger than I’d judged from shore. It shoved at my legs, trying to take my feet out from under me. I braced against rocks, gritting my teeth as the river tried to push me down.

My hands closed on wet fur, small and slick. I grabbed tight and pulled the creature against my chest. It clung to me—whether by instinct or desperation, I couldn’t tell—and I fought my way back to shore, heart hammering, lungs burning.

When I finally collapsed on the gravel, gasping for breath, the creature was still pressed against me, shivering violently.

That was the first time I really saw it.

It was small, maybe eighteen inches tall, ten or twelve pounds at most. Dark brown fur, plastered flat by the water, made it look even smaller. Its body was humanoid—arms, legs, torso—but the proportions were more like a primate’s. The hands had five fingers, each tipped with small, dark nails.

The face made me freeze.

Not human, not ape. Flat features, a small nose, a pronounced brow ridge too developed for any infant I’d ever seen. The mouth was small, the lower face delicate. And the eyes—

Dark brown, almost black, and aware.

Not just animal alertness. There was something thinking in there, something measuring me as surely as I was measuring it. The moment our eyes met, the hair on the back of my neck stood up.

It made a soft sound, somewhere between a whimper and a chitter. Its chest heaved with rapid breaths.

“It’s okay,” I said automatically, the way you talk to any frightened animal. “You’re safe now.”

I checked it quickly for injuries. No obvious wounds, no bent limbs. Just shaking, soaked, and terrified.

Another five minutes in that current and it would’ve been dead.

I sat there on the gravel, holding this strange little thing while my mind scrambled to file it under something familiar.

Baby monkey, I thought. Had to be. There are no native monkeys in Washington, but people smuggle exotic pets in more often than they should. Maybe someone’s illegal pet got loose. Maybe they released it out here when it got too hard to handle.

That explanation held together just long enough for me to cling to it.

The creature shifted in my arms and made a quiet, hesitant sound. It didn’t try to escape. That was wrong. A wild animal—any wild animal—would be scratching, biting, scrambling away. This one just watched me, breathing slowly, as if deciding.

I looked into those eyes again, and something deep inside me whispered: This isn’t a monkey.

“What are you?” I asked, voice barely above the sound of the river.

The creature tilted its head in a way that felt intentionally responsive, like it was considering the question.

That was when the fear landed. Not the fear of claws or teeth, but the fear that comes when you realize the world might be stranger than you thought.

I shoved that feeling aside.

Baby primate. Exotic pet. Weird, yes, but still explainable. I had coffee in the kitchen, a TV that barely worked, a file cabinet full of survey reports. I lived in a world of soil samples and board-feet, not in a world where impossible things crawled out of rivers.

My first instinct was to take it home, warm it up, call Fish and Wildlife in the morning.

But something in my gut pushed back, hard.

Taking it home felt wrong—not morally, but cosmically. Like crossing a line I couldn’t uncross.

“You belong out here,” I muttered. “Not in my kitchen.”

The creature had stopped shaking as much. Its breathing had steadied. It watched me with unnerving focus.

I stood up slowly, cradling it in my arms, and walked away from the river until I found a dry patch sheltered by a massive old cedar. The ground there was soft with moss and fallen needles. It felt…right.

“This is where you need to be,” I told it as I knelt and set it gently on the ground. “Your mother—or whoever—will find you here. Safer than the river.”

It sat exactly where I’d placed it, staring up at me. It made a questioning sound, no panic in it now, just…curiosity.

“You’ll be okay,” I said, though I couldn’t tell if I was trying to convince it or myself. “Your family will come for you.”

I backed away slowly. At about twenty feet, it finally moved. It turned and glanced into the forest, like it was orienting itself, then looked back at me one more time.

And damned if it didn’t nod.

Just a tiny, deliberate dip of the head.

Then it vanished into the undergrowth, moving with surprising speed for something so small.

I stood there shivering in my wet clothes, staring at the place it had gone. The rational part of me repeated words like “escaped pet” and “baby monkey” while another part sat there shaking its head.

I went home. I changed into dry clothes. I made coffee. I threw myself into my workshop, sanding down boards for a set of library bookshelves, breathing in sawdust and trying not to think about impossible things.

By the time darkness fell, I’d made a shaky peace with my rationalization.

It was just a baby monkey.

I almost believed it—right up until I glanced out the bathroom window that night and thought I saw something huge move between the trees.

Tracks and Night Visitors

Wednesday morning, before I’d even finished my first cup of coffee, I knew something was wrong.

It wasn’t anything obvious at first, just an awareness. That sensation you get when you’re sure someone’s watching you, even though you can’t see them.

I stood at the kitchen window, staring at the tree line, coffee cooling in my hand. The woods looked the same. Pale morning light. Mist along the ground. The sound of the river, steady as always.

But the forest felt different.

I told myself it was leftover nerves from the previous day and went about my morning routine. Shower, clothes, toast. Every time I passed a window, my eyes were dragged back outside.

By nine, I called myself an idiot and grabbed my gear. I had a stand of timber three miles north to assess before a logging company could bid. That was real work, the kind that kept my brain in useful channels.

Out in the woods with my increment borer and measuring tape, everything felt normal. I fell into the rhythm of counting rings and marking trees, noting root rot here and bark beetle signs there. These were problems I knew how to solve.

For six hours, I was just Gary the forestry consultant, not the guy who’d hauled a myth out of the river.

When I pulled back into my driveway around three, the first thing I saw were the prints.

They were in the soft dirt near my woodpile. Massive footprints, easily eighteen inches long, with five distinct toes. The stride between them was long, regular, and absolutely bipedal.

My stomach went cold.

I’ve seen bear tracks more times than I can count. These were not bear tracks. Bears have claws. Their toe arrangement is different. When they stand, they don’t leave this kind of consistent, walking pattern for yards.

These looked almost human—if a human had feet the size of dinner plates and weighed three hundred pounds.

The prints came out of the treeline, stopped about twenty feet from my house, then turned back and disappeared into the undergrowth.

Whatever it was had come close, looked my house over, and left.

“Hello?” I called toward the woods, feeling ridiculous. “Anyone there?”

Silence. The forest felt…muted. No birdsong, no squirrel chatter. Just the river and the sound of my own breathing.

I went inside and, for the first time in years, locked my door.

The rest of the afternoon, I pretended to do paperwork. Every page I looked at turned into those tracks in my mind. Every shadow outside the windows seemed to shift when I wasn’t looking directly at it.

Around six, I heard a thud outside. Heavy. Solid. I grabbed my flashlight and stepped out onto the porch.

Nothing. Yard, woodpile, workshop—all ordinary.

Then I saw it: a fresh, four-foot branch lying alone in the middle of the clearing between my house and the forest. It was newly broken, raw wood bright where it had snapped. And it hadn’t been there that morning.

I picked it up. There was nothing remarkable about it except its placement—dead center in the open ground between me and the trees, where nothing ever just “fell.”

A warning? A test? A message?

I tossed it back toward the tree line with more force than necessary and went inside. This time I checked the locks twice.

That night, I didn’t sleep.

Around two in the morning, I heard footsteps outside. Heavy, deliberate, walking a slow circle around the house.

I sat on the edge of my bed gripping the baseball bat I kept nearby, every muscle rigid. The steps stopped near my bedroom window. I could hear breathing. Deep. Controlled.

Whoever—or whatever—was out there knew I existed, knew where I slept, and was curious enough to come this close.

After an eternity, the footsteps moved away toward the forest. Branches snapped, brush rustled, and then there was only the river again.

I spent the remaining hours of darkness in my living room with every light on, the bat across my knees, watching the windows until dawn grayed the sky.

By Thursday morning, I felt like I’d aged a decade.

I tried to reason it out over a mug of coffee with shaking hands. The practical answer was a big black bear, maybe larger than average, sniffing around for food. They’d been sighted in the area before.

So I called Fish and Wildlife.

“Tom, it’s Gary,” I said when he picked up. “Something big’s been around the place. Large tracks. Night activity. Figured you should know.”

“What kind of tracks?” he asked.

“Bear…maybe. They’re big, though. Odd shape.”

“We’ve had reports of a large black bear near your area. Could be him looking for easy food. Keep your garbage secured. If it becomes a problem, we’ll set a trap.”

A bear. That was comforting, in a way. Bears are real. Bears are in books. Bears don’t stand outside your window at night and breathe like they’re thinking.

I tried to cling to the bear idea.

But that same afternoon, I found my workshop door ajar. Inside, nothing was missing, but things had been moved. Tools shifted. A half‑finished bookshelf nudged out of place, examined.

A wild animal might push its way in, knock things over. This felt like someone had investigated the space.

Later, I noticed a print on the dusty hood of my truck. A handprint. Too large to be human, with long fingers and no visible claw marks. On a nearby tree trunk, eight feet up, were deep scratches—too high for me to reach even if I jumped.

That night, the pattern escalated.

Footsteps around midnight. Then three heavy knocks on the side of the house.

Not random banging. Not an animal brushing past.

Three, evenly spaced, deliberate thumps.

“What do you want?” I shouted, voice cracking. “Who’s there?”

Silence.

Then the doorknob on the back door jiggled. Not rattled violently like a break‑in, but turned slowly, carefully, like someone testing whether it was locked.

It was.

After a moment, the knob stilled. Then a sound came through the wall, low and resonant. Not quite a growl, not language, but charged with emotion—frustration, maybe, or confusion.

After that, the footsteps retreated again.

By Friday morning, I was running on caffeine and nerves. My hands shook as I made coffee. Every creak of the house set my teeth on edge.

I knew I sounded crazy, even to myself.

But I also knew what I’d seen.

The Father Steps Forward

Around three Friday afternoon, sitting at my kitchen table trying to force myself through paperwork, I heard it again—that low vocalization from the forest.

Not a threat, not exactly. A call.

I went to the window.

The forest stood quiet, but the hair on my arms rose. Something large moved between pines, a flash of dark brown disappearing behind a stand of trees. Too big to be a bear on all fours. Too tall. Too deliberate.

“What do you want?” I said out loud, staring at the tree line. “What are you?”

Silence at first. Then, a little closer than before, another low sound. It wasn’t random. It had shape and intent, like syllables in a language I didn’t speak.

That night, as darkness settled and the familiar dread coiled in my stomach, I realized something.

Whoever was out there hadn’t attacked. They hadn’t smashed windows, killed livestock, or tried to break down doors. They’d circled, approached, tested.

Observed.

Like they were trying to figure me out.

Sometime around midnight, with footsteps crunching softly in the yard, I found myself standing at the back window whispering, “I’m not going to hurt you. Whatever you are, I’m not a threat.”

The footsteps stopped.

Silence stretched, thick and heavy.

Then a reply: that same low sound, softer now. Not friendly exactly, but not hostile either.

A conversation, of sorts.

On Saturday morning, the exhaustion hit like a freight train, but alongside it came a new realization.

The timing. The tracks. The cautious behavior. The fact that whoever was out there had spent days approaching but never crossing that last line.

I thought about the small creature I’d pulled from the river. Those eyes. That impossible nod.

“Oh my God,” I whispered into my empty kitchen. “You’re looking for someone.”

The baby.

Whatever species it was, it hadn’t been alone in the world. It had family. The same way a fawn has a doe somewhere nearby.

And the only thing that had changed in that forest in the last week was me pulling that baby out of the river and taking it inland.

If I were that baby’s father—and if I were built on a framework of caution and strength and a little more intelligence than humans were prepared to admit existed—I’d do exactly what was happening.

Track the last scent trail.

Circle the last known location.

Watch the last person who’d had my child in their hands.

They weren’t hunting me. They were evaluating me.

Once I saw it, I couldn’t unsee it.

I set my coffee down with a clink and stared into the trees.

“Okay,” I said quietly, feeling a little foolish and a lot terrified. “You’re the father. You’re looking for your baby. You want to know if I hurt it.”

From the forest, faint but clear, came that low sound again, closer than ever. Just beyond the tree line.

It wasn’t an answer, exactly.

But it wasn’t a denial.

An Offering in the Clearing

Saturday crawled by.

I couldn’t eat. Could barely sit still. My mind ricocheted between awe, fear, and a strange, fragile hope that whatever was out there might decide I wasn’t the enemy.

I kept coming back to a simple truth: hiding inside with the doors locked wasn’t saying anything useful. If this father was as cautious as he seemed, he needed something from me that wasn’t just absence of aggression.

He needed a sign.

Around four in the afternoon, I gathered supplies from the kitchen. Apples. Carrots. Leftover roasted chicken from Thursday. A bottle of water. I put them in a canvas bag and took a breath that felt like it scraped my lungs.

Then I walked out into the yard.

The late afternoon sun lay in slanting beams through the trees. I walked to the middle of the open ground between my cabin and the forest, the same area where I’d found that branch the other day.

I set the bag down on the grass and slowly backed away, hands open at my sides.

“I know you’re there,” I said, voice unsteady. “I know you’ve been watching. I want you to know I didn’t hurt your baby. I pulled it out of the river. I left it in the woods. It went back to the forest alive. I won’t hurt you. I won’t hurt it.”

The trees swallowed my words. The only reply was the wind.

After a few minutes, I turned and walked back to the house, resisting the urge to look over my shoulder.

The hours that followed were some of the longest of my life.

I watched from the window. The bag sat untouched. The forest remained still. Light drained slowly from the sky.

At 6:47 p.m.—I know the time because my eyes flicked to the clock right before it happened—I saw movement at the treeline.

Something enormous stepped out.

It emerged slowly, almost reluctantly, from the cover of the trees. At first it was just a block of darkness against the darker shadow of trunks. Then it moved forward, fully into the clearing, and there was no more hiding from what it was.

It walked upright. The way I do. The way you do.

Massive shoulders. Thick, powerful arms. The whole body covered in dark brown hair, with hints of gray at the shoulders and around the face. Even partially hunched, it stood easily a head and a half taller than me.

I stepped back from the glass, instinctively not wanting to crowd the window.

The creature moved with slow, precise caution, not like an animal stumbling out of cover but like someone who knew they were under observation and was fine with that.

It reached the bag and crouched.

That’s when I saw the face.

Flat, with a pronounced brow ridge and wide, flared nose. The jaw was strong, the mouth broad but closed. The eyes—those same deep, impossibly aware eyes I’d seen in miniature by the river—looked directly at my house.

Directly at me.

We locked gazes through my kitchen window.

The world narrowed until all that existed were those eyes, steady and dark and much too knowing.

He reached into the bag and pulled out an apple, rolling it in his massive hand, sniffing it. Then, without breaking eye contact, he did something that erased any hope that I could write this off as an overgrown ape.

He raised one hand, palm facing me.

A greeting.

I don’t know who moved first, him or me. My arm came up almost on its own. I mirrored the gesture.

For a heartbeat, we just stood there, two beings separated by fifty feet and an entire evolutionary gulf, hands raised.

His expression shifted, just slightly. Not a human smile; his face wasn’t built for that. But some subtle easing, some change around the eyes that carried a feeling of recognition.

Then he gathered the bag and its contents, turned, and walked back into the forest with a speed and smoothness that didn’t match his bulk.

One moment he was there.

The next he was gone.

I sank down at my table, hand still half raised, and let the reality crash over me.

Bigfoot.

Sasquatch.

The blurry shape in famous videos, the subject of campfire stories and crank phone calls to radio shows—standing in my yard, eating apples out of my grocery bag and acknowledging that I existed.

I started laughing. It sounded a little too high and a little too loud, and I wasn’t entirely sure if it was relief or the first crack of hysteria.

But beneath the shaking and the disbelief, another feeling wedged itself in:

He had accepted the offering.

He’d come out of hiding.

And nothing in his behavior—not one moment—felt hostile.

That night, when the footsteps came, I didn’t hide in the bedroom.

They approached the back of the house and stopped near the porch. That same low vocalization rolled through the wall, but this time it held a different tone.

Not a warning.

A call.

Heart pounding, I grabbed my flashlight and walked to the back door. I hesitated only a second before unlocking it and stepping out.

My flashlight beam swept across the clearing and landed on two amber eyes reflecting the light, about thirty feet away.

He stood fully visible at the edge of the trees. Up close, he was even more impressive. Seven feet tall if he was an inch, shoulders as broad as a doorframe. The hair looked longer around his head and shoulders, almost like a natural cloak. Gray peppered his muzzle and temples.

He watched me, unmoving.

I kept the beam low, not shining directly into his face. He made a soft sound, then reached into the bag he still carried and pulled out another apple.

He held it up, then touched it to his chest, then gestured toward me.

Thank you.

“You’re…welcome,” I managed, voice barely more than a breath.

“Your baby,” I added, forcing the words out. “It’s okay. It went back into the forest. It was alive.”

He tilted his head, listening. Then he made another sound, different cadence, and brought both arms in toward his chest, hands cupped protectively.

Safe.

I understood him.

A knot I hadn’t realized I’d been carrying loosened in my chest.

“Good,” I said. “Good. I’m glad.”

We stood there in the cool night air, two silhouettes under a sky full of stars, communicating in fragments of sound and imitated gestures. It was clumsy and incomplete and more profound than anything I’d ever experienced.

Then he bent, picked something up from the ground, and stepped forward.

Every instinct screamed at me to back away, but I held my ground, fingers tight on the flashlight. He stopped about ten feet from the porch and carefully set an object down on the ground, then retreated a few steps, watching me with intent focus.

I edged forward, beam dropping to the object.

It was a piece of wood, maybe two feet long, bark stripped and surface smoothed. Carved into it, with surprising precision, were two figures.

A small one.

And a larger one.

Lines connected them. Between them. Around them.

Family.

My throat closed. This was more than a gift. It was a record. It was him saying, This is what you saved. This is what you did.

“It’s beautiful,” I said, voice rough. “Thank you.”

He made that soft, rumbling sound again—the one that felt almost like contentment—then turned and walked toward the trees. Just before the darkness swallowed him, he paused, looked back, and raised his hand again.

I raised mine.

Then he was gone.

A Secret Friendship

Sunday morning, I set the carved branch on my mantle, next to a photograph of Linda.

Two impossible connections, side by side.

I spent the afternoon in my workshop carving.

I’m not an artist, but I work with wood most days of my life. I took a block of cedar and shaped it into three figures: a large one, a smaller one, and a human, all standing side by side on a shared base.

Different, but together.

As the sun dipped low, I carried the carving to the same spot in the clearing where he’d left the bag and placed it gently on the ground. Then I went back to the house and waited.

Twilight deepened. The clearing dimmed.

He came.

He moved straight to the carving, picked it up, and turned it over in his hands, examining each figure in turn. Then he looked at my house.

He made a low, rolling sound I’d never heard from him before, full of something I didn’t need to be a linguist to recognize.

Emotion.

Gratitude. Recognition. Maybe even something like affection.

He pressed the carving gently to his chest, then retreated to the trees—but not before raising his hand again in that now-familiar gesture.

In the days that followed, a pattern formed as naturally as sunrise.

Every evening, just after sunset, he would appear at the edge of the clearing. Sometimes he came close enough to take food directly from where I set it. Other times he remained in the shadows, watching.

We created a small vocabulary of gestures.

Raised hand: greeting, peace.

Hand to chest: self, or feeling.

Point: direction, object.

Hands brought together: together, family.

He brought me gifts from time to time. A chunk of naturally fractured obsidian that looked like black ice. A pinecone unlike any I’d seen, massive and spiraled. Flat stones etched with simple shapes.

One evening he brought a larger slate, covered in scratched symbols—circles, wavy lines, triangles. He pointed to a circle with radiating lines, then gestured toward the sky.

Sun.

A wavy line, then toward the river.

Water.

He had a written system. Crude, but real.

I drew in the dirt with a stick: a rough house shape. Then pointed at my cabin. He watched closely, then scratched his own symbol—a semicircle beneath a jagged line of peaks.

His shelter, in the mountains.

We spent that evening building a shared lexicon, two species meeting halfway across a chasm with sticks and scratches and patience.

At some point I started thinking of him as Ridge.

I never said it aloud, but the name fit—solid, enduring, part of the landscape. He seemed older, the gray in his hair and the lines in his face hinting at a long life lived in careful shadows.

And then, one Thursday evening in early July, he brought his child.

I was sitting on the back porch as usual when I heard multiple steps from the forest. Lighter ones alongside the familiar heavy cadence. My heart leapt into my throat as he emerged from the trees, and beside him, smaller and more hesitant, was the little one from the river.

It had grown. Nearly two feet tall now, fur fluffier and cleaner than the drowned rags I’d first seen. It moved with a curious confidence, pausing often to look at me, then at Ridge, then back at me.

When it saw me, it froze, then pressed against Ridge’s leg.

He made a soft, reassuring sound, laid a big hand on the child’s head, then gestured to me in the sign we’d established: friend. Safe.

The young one studied me with those same dark eyes I’d seen by the river. Then, cautiously, it stepped forward. Ten feet. Eight. Five.

“Hey there,” I said quietly. “Remember me? I’m the guy who pulled you out of the water.”

It tilted its head, then did something that hit me harder than I expected.

It touched its own chest, then gestured toward me, then made a soft, gentle sound that matched the tone Ridge used when thanking me.

It remembered.

“You’re welcome,” I said, voice thick. “I’m glad you’re okay.”

It took another step and extended a small hand toward me. I understood.

Permission.

I reached out slowly, palm up. Its hand settled against mine.

Warm. Soft fur. Small fingers, surprisingly strong.

The contact was brief, but it might as well have lasted an hour. A bridge, crossing an impossible gap.

Then it withdrew, made that grateful sound again, and bounced back to Ridge’s side.

Ridge watched all of this with an expression I didn’t need to share a species to read.

Pride. Relief. Trust.

He brought his child to meet me—to show the young one I was safe. To say, in the clearest way he could, This human is family.

From then on, visits were sometimes just Ridge, sometimes Ridge and the young one. I left food; they accepted it. Ridge showed me plants they favored, miming plucking and eating. He demonstrated how they moved unseen through the forest, how they used wind and terrain to stay downwind of humans.

In return, I showed him tools. Carefully. Slowly.

He handled my hammer with fascination, turning it, feeling the weight. My axe he treated with respect, never swinging it, only mimicking the motion once and nodding as if to say, I understand.

On a flat piece of wood, I drew a crude photo of a tree, then showed him an actual photograph from a magazine. Watching him puzzle out that the flat image represented a real, three‑dimensional thing was like watching a child understand a new word.

Awe. Then delight.

The World Closes In

By mid‑August, our silent friendship had become part of my life as naturally as checking the mail.

Which made it easy to forget that I lived in a world full of other humans who might not be so gentle with a seven‑foot biped they couldn’t explain.

I was reminded of that the day I ran into Tom Patterson at the grocery store in town.

“We’ve had some reports,” he said casually, leaning on my open truck tailgate while I loaded groceries. “Hikers seeing things near your place. Big tracks. Strange sounds.”

The world narrowed to that word: tracks.

“You noticed anything unusual?” he asked.

I made my face go blank. “Nothing out of the ordinary. Bears, elk. The usual. People see a bear stand up and suddenly it’s a monster.”

He chuckled, but his eyes stayed sharp. “We’ll probably send a team to set up some trail cams next week. Just a heads up.”

I drove home too fast, the groceries blurring in my peripheral vision. Trail cameras. Survey teams. Scientists.

Ridge. The child.

That evening, when Ridge appeared, I was jittery and on edge. He noticed immediately, head tilting, eyes narrowing with concern.

I grabbed a stick and drew in the dirt with frantic energy: little faceless humans with rectangles in their hands—our symbol for cameras—arrows pointing into the forest. I circled them and made a harsh, slashing gesture. Danger.

Ridge watched, then took the stick. He drew his shelter symbol, far away from my house symbol, then made a motion like pulling branches in front of something.

Hide.

I exhaled. He understood. They’d go deeper into the forest, avoid the areas where humans would tromp. Then he surprised me.

He drew my symbol—that little simplified man we’d been using for me—and moved it closer to his shelter symbol. Then he looked at me and made the gesture we’d come to use for question, inviting.

He was asking if I wanted to see where he lived.

If I wanted to step fully into his world.

“Yes,” I said immediately. Then slower, conveying with gesture and tone, Yes. I want to see.

We arranged it for dawn two days later.

He’d come close to my property line. I’d follow.

The intervening days were full of tension. A research team arrived in their official vehicles, led by a woman named Dr. Sarah Mills and accompanied by Tom and a younger tech named Kevin. They set up trail cams, checked meadows and game trails, measured tracks—some Ridge had left days before, back when the forest seemed like ours alone.

They found some of his prints near a creek.

“What do you think?” Dr. Mills asked, showing me a plaster cast.

“Distorted bear,” I lied. “Mud can play tricks.”

She didn’t buy it, but without more, she couldn’t prove a thing.

I hung a red cloth on a tree near my property line—the danger signal Ridge and I had agreed on. Until that cloth changed, he and his family would stay away.

Except for the one time they couldn’t.

Into His World

Dawn broke clear and cold on Saturday when we’d agreed to meet.

I stood on my porch with a small backpack—water, some food, basic first aid—feeling like a man about to step through a mirror.

Ridge appeared from between the trees with the young one at his side. He approached closer than ever before, close enough that I could see the individual strands of gray in his hair.

He gestured.

Come.

We walked.

And walked.

Ridge moved through the forest as if it were a map only he could see, slipping between dense thickets, skirting fallen logs, leading us up and over low ridges and across narrow streams. Had I been alone, I would’ve lost my bearings within minutes. With him, I never doubted he knew exactly where we were.

The young one trotted beside him, occasionally glancing back at me with an eager spark in its eyes. This was an adventure, and I’d been invited.

After more than an hour, the terrain changed. We descended into a small hidden valley ringed on three sides by steep slopes. Trees grew close at the edges, but the center opened into a mossy, sheltered space.

I never would have found it on my own.

Built into a rock overhang, partially hidden by carefully arranged branches and brush, was their home.

At a glance, it could be mistaken for natural debris. Up close, it was deliberate.

Branches woven together formed walls that blocked wind but allowed air to circulate. The overhang sheltered the main space. Inside, I saw layered bedding made of dried grasses, ferns, and moss. Channels in the earth diverted rain runoff away from the sleeping area.

Ridge stood tall, then gestured with unmistakable pride.

This is ours.

He showed me more.

A shallow pit covered with flat stones where food was stored cool. A cluster of shaped stones—tools for pounding, scraping, cutting. On a flat rock surface at the back, several pieces of wood and slate etched with more of those symbols, arranged as carefully as any bookshelf in town.

This wasn’t just survival. This was culture.

The young one scampered inside and returned with one of the carved slates, thrusting it toward me eagerly. Ridge made a fond, exasperated noise that translated perfectly across the species divide: Show-off kids are the same everywhere.

We spent hours there. I asked questions with gestures; Ridge answered with demonstrations. When I pointed to the symbols, he indicated seasons, movements of herds, safe paths, dangerous places. Their entire world mapped in scratches and shapes.

By the time we made the long trek back toward my property in the afternoon, my legs ached and my mind buzzed.

At the edge of the forest, Ridge stopped.

He turned to me and made a long, careful series of gestures: his shelter symbol, the broader forest, my house. Then he touched his chest, and mine.

You’ve seen my world.

You know my home.

You are part of this now.

“I’ll protect it,” I promised, voice steady. “No one will know. No one will find you because of me.”

He held my gaze for several long seconds, then nodded—a slow, deliberate motion—and disappeared into the trees with the young one.

I walked the last quarter mile home alone, feeling the weight of what I’d just been given.

Trust.

Responsibility.

Family, whether either of us had planned it or not.

Some Secrets Are Worth Keeping

The research team stayed another few days.

They found more anomalies. A few more prints. Vague sounds on audio recordings. They stumbled near Ridge’s primary shelter at one point, but by then he’d shifted his family to a secondary site deeper in the mountains.

Every time they found something too interesting, I was there with plausible alternative explanations. Old hunter shelters. Distorted tracks. Tree falls that “just looked weird in this light.”

Dr. Mills eyed me with a mixture of frustration and curiosity. I could see the gears turning in her mind, the scientific hunger to name and classify what she almost—but not quite—believed she’d brushed up against.

“If you ever see something truly unusual out here,” she said as they loaded up their vehicles to leave, “I hope you’ll consider calling us.”

“I will,” I lied.

When their taillights finally disappeared down the logging road, the forest exhaled with me.

I walked straight to the warning tree and pulled down the red cloth, replacing it with white.

Safe.

That evening, Ridge limped into the clearing, the young one at his side. The foot he’d caught in an old trap a few days earlier—yet another echo of our first meeting—was still tender but healing.

I had extra food set out. We didn’t need symbols that night. Our relief was its own language.

In the months that followed, our lives settled into a new rhythm. Ridge’s foot healed completely. The young one grew taller, bolder, more independent, but never disrespectful. Ridge corrected it gently when it strayed too close to my tools or tried to sneak onto the porch uninvited.

We added symbols to our shared vocabulary. Stars. Snow. Danger. Safe. Change.

One evening, Ridge brought me a new piece of carved cedar.

On it, in our mixed set of symbols, he’d etched a story—not just his, not just mine, but ours.

A river.

A small figure in the water.

A human figure pulling it out.

A larger figure approaching the human’s shelter.

Hands joined.

Family.

I hung it on the wall next to Linda’s photograph.

Two stories of love and loss and impossible connection, side by side.

Sometimes, on still evenings when the sun turns the clouds over the ridgeline gold, I sit on my back porch and think about what would happen if I picked up the phone and told the world what I know.

I picture helicopters beating the air above the treetops. Scientists staking out the valley I visited, measuring everything, tagging anything that moved. Hunters with high‑powered rifles and cooler chests, dreaming of a trophy no one else had.

Ridge in a cage, eyes dulled under fluorescent lights.

The young one in a concrete pen, poked and prodded in the name of knowledge.

No.

Some truths don’t belong on television specials. Some miracles don’t need press conferences. Not everything real has to be publicly proven to matter.

I thought I was saving a baby monkey that day in June.

Instead, I stepped sideways into a different world. One where the forest is not just trees and water and wildlife, but neighbors I’ll never introduce to anyone else. One where a seven‑foot father stands at the edge of my clearing at dusk and raises his hand in greeting, and I raise mine back without fear.

I sit here now as the light fades, coffee cooling in my hands, listening for the familiar footfalls at the treeline. The river’s song threads through the evening, unchanged. Birds settle. The air cools.

There—between the firs—a tall shape moves.

He steps out, the young one—taller again now—beside him. He lifts his hand.

My own hand rises before I think about it.

Some secrets are worth keeping.

Some friendships are worth protecting.

And some impossibilities, against all odds, turn out to be the most real thing in your life.

News

Rob Reiner’s Tragic Final Days – The Sh0.cking Truth Behind His Death Revealed!

Rob Reiner’s Tragic Final Days – The Sh0.cking Truth Behind His Death Revealed! The world of cinema was plunged into…

‘Stop using it for votes!’: Sen. Moreno ‘exposes’ Obamacare ‘lies’ in explosive hearing

‘Stop Using It for Votes!’: Sen. Moreno ‘Exposes’ Obamacare ‘Lies’ in Explosive Hearing WASHINGTON D.C. — In a room originally…

Hearing ERUPTS After Slotkin CONFRONTED Kristi Noem About Deporting U.S. Citizens With Cancer

Hearing ERUPTS: Senator Slotkin Confronts Kristi Noem Over “Sloppy” Deportation of U.S. Citizens and Children with Cancer A routine Senate…

Rep. Jasmine Crockett Hits Back at AG Pam Bondi’s Retribution Threat

“Right vs. Wrong”: Rep. Jasmine Crockett Fires Back at AG Pam Bondi Over Retribution Threats and the “Politicization” of Justice…

GOP CongressWoman Hariette Hageman Totally HUMMILIATES Adam Schiff Entire Democrats left SPEECHLESSS

The Unraveling of a Narrative: How Harriet Hageman’s Direct Challenge Left the House Floor in Silence In a legislative chamber…

APPLAUDS Break-Out As Democrat POLICE MAN Who Tried to ARREST Ben Shapiro Get’s Totally DESTROYED.

APPLAUDS Break-Out: The Day a University Tried to Arrest Ben Shapiro and Lost the Narrative What happened at DePaul University…

End of content

No more pages to load