In 1988, He Asked Bigfoot About the Famous Bigfoot Video Filmed in 1967. Its Answer Will Sh0.ck You!

The Last Witness of Bluff Creek

When I finally worked up the courage to ask Bigfoot about the Patterson–Gimlin film—that grainy 1967 footage everyone’s seen—I expected denial, confusion, maybe aggression.

What I got instead was a reaction so profound, so unmistakably emotional, that it shattered every assumption I’d ever made about intelligence, memory, and what it means to lose someone you love.

The way he touched his own chest, then gestured out toward the forest with something that looked heartbreakingly like grief, told me more about that famous footage than twenty years of debate ever could.

My name is Henry Walker, and I’m thirty‑four years old in the autumn when this begins.

I live alone on a forty‑acre property about sixty miles northeast of Seattle, in the foothills of the Cascade Mountains. I moved here in 1985 after my divorce, bought the land cheap because it was too isolated for most people’s taste, and set up a small woodworking shop in the barn. I make custom furniture—tables, chairs, cabinets—and sell them through a couple of stores in Seattle and Everett.

It’s a solitary life, which, or so I used to think, suits me fine.

It’s October 1988, and the autumn colors are spectacular this year. The maples are brilliant red and orange, the oaks a deep gold, all layered against the dark green of Douglas fir and western red cedar that dominate the landscape. My property backs up against thousands of acres of national forest, which means I rarely see anyone. The nearest neighbor is three miles down a gravel road that turns to mud whenever it rains, which is often.

I’ve always been a skeptic. Ghosts, UFOs, Bigfoot—all of it struck me as wishful thinking or outright hoax. Growing up in suburban Tacoma, the wilderness was something you visited on weekends, not something you lived in. Even after moving out here, that mindset stuck. Sure, there were black bears and cougars in these mountains. But Bigfoot? Come on.

That started to change about six weeks ago, in early September.

I. The First Signs

I’d been working late in the shop, pushing to finish a rush order for six dining chairs. It was around eleven at night when I finally shut down the table saw and swept up. The shop is about fifty yards from the house, a small two‑bedroom cabin with a metal roof and a wood stove that carries me through the winter.

As I was walking back, I heard something.

Not the usual night sounds—owls, rustling leaves, distant coyotes. This was different. A low, resonant sound, almost like a very deep hum or groan. It seemed to come from the tree line about a hundred yards away, where my property meets the national forest.

I stopped and listened.

The sound came again, louder than the silence around it. A vibration more felt in my chest than heard with my ears.

“Hello?” I called out, feeling foolish immediately. “Anyone there?”

No response. After a few seconds, the normal night sounds resumed. Crickets. Wind in the trees.

I went inside, chalking it up to some odd bear or elk vocalization. But it bothered me. That sound had been too low, too steady. Not quite animal. Not quite human.

Two days later, I found the first footprint.

I’d walked out to check my firewood supply—three cords stacked near the shop, ready for winter. In the soft earth beside the woodpile was a print. Massive. At least sixteen inches long. Shaped like a human foot, but much wider, with clear impressions of five toes.

I stared at it for a long time, my mind trying to rationalize what I was seeing. A prank, had to be. Someone had carved a giant wooden foot and stamped my yard.

Except I was miles from anyone. The print was deep, suggesting something heavy had made it. And there was only one. If someone was pranking me, wouldn’t there be a trail?

I measured it with a tape: seventeen inches long, seven inches wide at the ball. The toes showed clear definition with what looked disturbingly like toe pads and even the hint of dermal ridges.

“This is crazy,” I muttered. “There’s got to be a logical explanation.”

But over the next two weeks, I found more prints. Never in a long trail, just isolated impressions here and there, always in soft earth near the forest edge. And other signs: tree branches bent at heights I couldn’t reach even with a ladder; a strange musky smell that would appear suddenly and vanish; and more of those deep, resonant vocalizations at night, always from the forest.

I started staying up later, watching the tree line from my kitchen window. I kept binoculars on the sill. I even borrowed a friend’s bulky Panasonic VHS camcorder and kept it by the door, though I felt ridiculous doing it.

The rational part of my brain insisted there had to be a mundane explanation: a bear with deformed paws, a particularly large person living rough in the national forest, teenagers from town messing with the hermit woodworker.

But the skeptic in me was starting to crack.

Because deep down, I was beginning to suspect what I was dealing with.

And that suspicion terrified and fascinated me in equal measure.

II. The First Wave

The first actual sighting happened on Monday, October 3rd, 1988.

I remember the date because it was the day my ’85 Chevy pickup had rattled all the way back from Everett, and I was already dreading a repair bill. I pulled up to the cabin around four in the afternoon. The October sun was low, throwing long shadows across the clearing. I grabbed my toolbox from the truck bed and headed for the shop, planning to get a couple of hours of work in before dinner.

That’s when I saw it.

Movement at the tree line. Large. Upright.

My first thought was bear—we have plenty of black bears. But as my eyes focused, my brain refused to cooperate with the usual explanations.

It was standing. Not reared up awkwardly on hind legs the way a bear sometimes does, but standing naturally, comfortably, like a person.

Only it wasn’t a person.

It was massive. At least seven feet tall, maybe more. Covered in dark brown fur. The body structure was humanoid—broad shoulders, long arms, bipedal stance—but the proportions were wrong. Too large. Too powerful.

We stared at each other across roughly seventy yards of open clearing.

My hand was still on the truck bed, my toolbox forgotten. My heart hammered so hard I could hear it in my ears. The creature—because what else could I call it—tilted its head, a remarkably human gesture of curiosity.

Then it raised one massive arm and made a small, controlled gesture.

A wave.

Not threatening. Not a bluff charge.

Just an acknowledgement.

I couldn’t move. Couldn’t speak. Could barely breathe. After what felt like an eternity but was probably only thirty seconds, the creature turned and walked back into the forest. Not hurrying. Not fleeing. Just leaving, moving with a grace that seemed impossible for something so large.

I stood there for another five minutes, waiting for my heart to slow and for my brain to regroup, to offer hallucination or misidentification as escape routes.

But deep in my gut, I knew.

There was a Bigfoot living in the forest behind my property, and it had just introduced itself.

That night, I couldn’t sleep. I kept replaying the encounter in my mind, analyzing every detail—the way it stood, the way it moved, that wave. Almost friendly. Almost… communicative.

I dug out a box of old magazines and paperbacks I’d been meaning to throw away. Buried in there was a dog‑eared book about unexplained phenomena I’d picked up at a garage sale years ago. I found the chapter on Bigfoot and started reading.

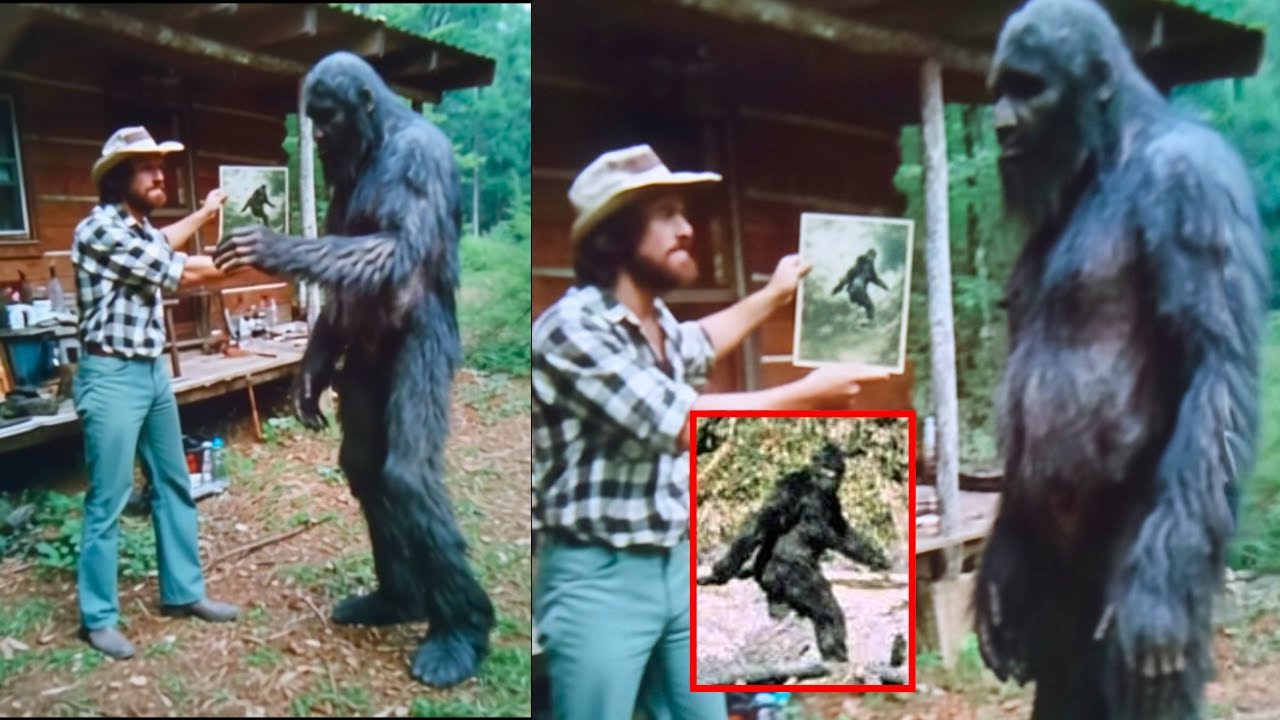

The descriptions matched what I’d seen: the height, the build, the way it moved. And there, in a grainy black‑and‑white photograph, was a still from the famous Patterson–Gimlin film shot in Northern California in October 1967.

Frame 352.

The clearest shot of the creature in the footage, mid‑stride, looking back over its shoulder at the camera.

I stared at that image for a long time. The creature in the photo looked remarkably similar to what I’d seen. Same basic body structure, same way of moving.

The film had been analyzed by experts for over twenty years. Some called it a hoax; others swore it was genuine. Looking at it now, after what I’d seen, I believed it was real.

Which raised an uncomfortable question.

Was the creature I’d seen the same one from the film?

That was impossible. The film was over twenty years old. Even if these things existed, surely there was more than one.

But what if there wasn’t?

What if I was looking at one of the last of its kind?

The thought was both thrilling and deeply, deeply sad.

III. Building a Bridge

Over the next few days, I became obsessed.

I started leaving food out.

Apples from my tree. Leftover bread. Once even some smoked salmon I’d splurged on in Everett. I’d place the offerings at the edge of the clearing near where I’d first seen the creature and watch from my kitchen window.

The food always disappeared between dusk and dawn.

I never saw him take it, but I knew he was watching. I could feel it sometimes—that prickly sensation of being observed.

On October 10th, exactly a week after the first sighting, I decided to take a risk.

At dusk, I walked out to the tree line carrying a plate of food: roast chicken, mashed potatoes, carrots. I set it on a stump about ten feet into the forest, then backed away to the middle of the clearing.

“I know you’re there,” I called out, feeling absurd but too far in to stop. “I’m not going to hurt you. I’m not going to tell anyone about you. I just… I want to understand.”

Silence.

Just evening birds and the rustle of leaves.

“I’ll be here,” I added. “Same time tomorrow. If you want to, I don’t know, communicate somehow. I’ll be here.”

I went back to the house and watched from the window.

About twenty minutes later, as full darkness settled, I saw movement. The creature emerged from deeper in the forest, approached the stump, and took the plate. It didn’t eat there—just took it and retreated.

But before disappearing, it stopped and looked directly at my house. Directly at the kitchen window where I stood.

And it nodded. Once. Deliberately.

My hands shook as the realization sank in.

It understood. Maybe not my specific words, but the intent, the offer.

That was the beginning.

We established a pattern over the next two weeks. Every evening at dusk, I’d bring food to the stump. Every evening, sometime after I’d gone back to the house, the creature would emerge and take it.

We were developing a routine. A mutual understanding. I was feeding him. He was tolerating my presence.

But I wanted more than tolerance.

I wanted communication.

On October 17th, I tried something different.

Instead of leaving the food and retreating, I sat down on the ground about twenty feet from the stump. Cross‑legged, hands visible. The plate of food sat on the stump between us like an offering at a border crossing.

Dusk bled into night. Mosquitoes did their best to drive me crazy, but I didn’t move.

After about forty minutes, I heard movement.

He emerged from the trees slower than usual, more cautious. He stopped when he saw me sitting there. We looked at each other in the fading light.

I could see his features more clearly now: dark brown fur graying around the face and shoulders; deep, dark eyes watching me with obvious evaluation.

This wasn’t just an animal.

There was thought behind those eyes. Reasoning.

Very slowly, I raised one hand in a wave—the same gesture he’d made to me two weeks before.

He tilted his head, considering.

Then he raised his own massive hand and waved back.

Careful, controlled. An almost perfect mirror.

My heart pounded, but I stayed as calm as I could. I pointed at the plate on the stump, then gestured toward him: an invitation.

He approached slowly, eyes never leaving me. At fifteen feet he stopped, reached out with one long arm, and picked up the plate without coming any closer.

Then he did something that took my breath away.

He sat down. Right there. Fifteen feet away. Cross‑legged, just as I was.

He ate while watching me. Not tense, not fully relaxed either. Just… present.

We sat like that for about twenty minutes. Me barely breathing, afraid to break whatever fragile spell was holding. Him eating methodically, occasionally glancing at me but mostly focused on the food and the quiet.

When he finished, he set the plate carefully on the ground and stood. He looked at me for a long moment, then made that low, resonant hum I’d heard from the forest before—softer now, almost gentle.

Then he turned and walked back into the trees.

I sat there for another hour after he left, mind racing.

We’d just shared a meal.

And he’d deliberately mirrored my posture, my gesture.

He was trying to build a bridge.

IV. The Camera He Already Knew

Over the following days, our encounters became more frequent. He’d sit with me most evenings now. Sometimes only a few minutes. Sometimes an hour or more.

I started bringing a notebook, documenting everything—the way he moved, the sounds he made, the gestures he used. I was slowly building a vocabulary of his body language.

On October 23rd, I brought something new: a Polaroid camera, an old Sun 600 I’d had for years.

I’d debated this for days. I wanted proof, but I was terrified of breaking the trust we’d built.

When he emerged and saw the camera in my hands, he froze.

His posture changed instantly—tense, wary. He made a short, sharp sound, almost like a warning bark.

I set the camera gently on the ground beside me and raised my hands to show they were empty.

“It’s okay,” I said softly. “It’s just a camera. It takes pictures. I won’t use it if you don’t want me to.”

He stared at the camera for a long time.

Then he approached cautiously and picked it up.

The camera looked tiny in his massive hands. He examined it from all angles, making soft humming sounds. Then he did something that shocked me.

He held it up to his face and looked through the viewfinder at me.

He understood what it was.

Or at least he understood the concept.

He set the camera down between us and backed away slightly. Then he gestured: pointed at the camera, then at himself, then made a pushing‑away motion with his hands.

No. Don’t photograph me.

“Okay,” I said out loud. “No pictures. I understand.”

He nodded.

Actually nodded.

That night, lying in bed, I couldn’t stop thinking about it.

How did he know about cameras? How long had he been observing humans? Why was he so adamant about not being photographed?

The answer seemed connected to the same thing that had been nagging at me for weeks: the Patterson–Gimlin film.

That famous 1967 footage from Bluff Creek.

The way he reacted to cameras suggested experience—maybe even trauma—with being filmed or photographed.

But how do you ask a being who doesn’t speak your language about an event that happened twenty‑one years ago?

You use pictures.

V. Asking About Bluff Creek

On October 28th, I decided to try.

It might end everything. It might scare him off permanently, destroy the fragile trust we’d built. But the question burned.

Did he know about that footage? Had he been there? Did he understand what had happened in 1967?

That afternoon, I went to the library in Everett and made photocopies—still images from the film, including frame 352 and several other angles.

That evening, he arrived at our usual spot just after sunset and sat down in his customary place, about twelve feet away. I’d noticed over the weeks that he’d been sitting closer each time.

I set out the food as usual, but kept the manila folder on my lap.

After a few minutes, I took a deep breath and pulled out the first image: frame 352, the iconic shot of the creature mid‑stride, looking back.

I held it up so he could see clearly.

The reaction was immediate and profound.

He went completely still. Every muscle tensed. He made a sound I’d never heard before—not aggressive, but pained. Mournful.

His eyes locked on the image with frightening intensity.

“I’m sorry,” I blurted, ready to put it away. “I didn’t mean to upset you.”

But he wasn’t just upset.

He leaned forward, staring at the photo. Then he reached out, gesturing for me to hand it to him.

I did.

He held the paper delicately in both hands, bringing it close to his face. His fingers traced the outline of the figure in the image.

Then he did something that made my chest tighten.

He touched the photo gently, almost reverently.

He pointed at it, held up two fingers, then pointed at his own chest, then back at the photo.

Two of us.

“You were there,” I whispered. “When this was filmed.”

He nodded slowly.

Then he made another gesture. He pointed at the figure in the photo and mimed cradling something small in his arms. Young. Then he pointed to himself and gestured taller, bigger.

The figure in the film wasn’t him.

It was someone younger. Smaller.

Someone he knew.

“That’s someone you knew,” I said, understanding dawning. “Someone younger than you.”

He made that mournful sound again and nodded.

Then, in a series of gestures, he told me the story as best he could.

He pointed at the photo, then walked his fingers along the ground—peaceful movement. Then his hands flew apart: something sudden, startling. He mimed fear—startled, running. He pointed to himself and made a searching gesture, looking all around.

Then he brought his hands together, palms empty.

Gone. Never found.

My throat tightened.

When that footage was taken in 1967, he’d been there—watching from the trees, perhaps, or nearby. The creature on film had been someone he knew. Someone younger. Possibly his offspring, or a younger member of his kind.

And when Roger Patterson and Bob Gimlin showed up with their camera, when that young one was caught on film, everything changed.

They were scattered. Separated.

And he’d never found them again.

“You’ve been looking for them,” I said quietly. “For twenty‑one years. That’s why you’re here, so far from California. You’re still searching.”

He looked at me with those dark, intelligent eyes, and I saw something I’d never expected to see in a creature like this.

Grief.

Deep, profound grief that transcended species.

He set the photo down carefully and made another gesture: two fingers held up—two of us—then just one—now only one. Then he spread his arms wide, indicating the vast forest around us.

Alone. Searching for twenty‑one years.

“I’m so sorry,” I said, and I meant it. “I can’t imagine. I’m so, so sorry.”

He picked up the photo again and stared at it for a long time. Then he touched his chest, then touched mine.

Connection.

He was sharing this with me because I was the first being in probably decades who’d shown him kindness without threat. The first one he trusted enough to reveal this pain to.

I pulled out the other images. He studied each, pointing out a blurred patch of disturbed vegetation in one frame and tapping his own chest.

There. I was there.

“You were watching from the trees,” I said. “Trying to protect them.”

He nodded, then made a gesture of helplessness—hands spread, shoulders slumped.

Couldn’t help. Too dangerous. Too many humans. Had to run.

And I understood the full tragedy of the Patterson–Gimlin film.

Yes, it was real. Yes, it captured something extraordinary.

But it also captured a catastrophe.

A family—maybe a small group—scattered by the presence of humans with cameras. A young one exposed and vulnerable. The others forced to flee, to scatter, to lose each other in the vast wilderness.

Twenty‑one years later, one of them was still looking. Still hoping. Still searching these mountains, these forests, for the one caught forever in that footage.

“Is that why you revealed yourself to me?” I asked. “Because you’re tired of searching alone?”

He looked at me for a long moment, then made a gesture encompassing weariness and resignation. Then he pointed at me, at my house, at the isolated property around us.

Alone.

“You’re alone too,” I said.

“Yeah. I am.”

He made that soft humming sound of acknowledgement. Then he gathered the photos carefully and handed them back to me. He pointed at the images, then at his eyes, then cupped his hands as if holding something fragile.

Remember. Protect. Don’t share.

“I won’t tell anyone,” I promised. “No cameras. No proof. No stories. Just between us.”

He nodded, satisfied. Then he pointed one last time at frame 352, at the forest beyond us, and made a questioning gesture.

Still looking. Still hoping.

“I hope you find them,” I said. “I really do.”

He made a soft sound that might have been gratitude. Then he walked back toward the forest, his massive form disappearing into the darkness.

At the tree line, he stopped and looked back.

Just like in the famous footage.

And I wondered if that look, that checking back, had become a habit—a reflex born from the day he’d lost someone and never stopped hoping to see them again.

That night, I spread the photos on my kitchen table and sat with the weight of what I’d learned.

The Patterson–Gimlin film wasn’t just the best evidence of Bigfoot ever recorded.

It was documentation of a tragedy.

And the only witness who truly understood it had just asked me to keep it secret.

News

Rob Reiner’s Tragic Final Days – The Sh0.cking Truth Behind His Death Revealed!

Rob Reiner’s Tragic Final Days – The Sh0.cking Truth Behind His Death Revealed! The world of cinema was plunged into…

‘Stop using it for votes!’: Sen. Moreno ‘exposes’ Obamacare ‘lies’ in explosive hearing

‘Stop Using It for Votes!’: Sen. Moreno ‘Exposes’ Obamacare ‘Lies’ in Explosive Hearing WASHINGTON D.C. — In a room originally…

Hearing ERUPTS After Slotkin CONFRONTED Kristi Noem About Deporting U.S. Citizens With Cancer

Hearing ERUPTS: Senator Slotkin Confronts Kristi Noem Over “Sloppy” Deportation of U.S. Citizens and Children with Cancer A routine Senate…

Rep. Jasmine Crockett Hits Back at AG Pam Bondi’s Retribution Threat

“Right vs. Wrong”: Rep. Jasmine Crockett Fires Back at AG Pam Bondi Over Retribution Threats and the “Politicization” of Justice…

GOP CongressWoman Hariette Hageman Totally HUMMILIATES Adam Schiff Entire Democrats left SPEECHLESSS

The Unraveling of a Narrative: How Harriet Hageman’s Direct Challenge Left the House Floor in Silence In a legislative chamber…

APPLAUDS Break-Out As Democrat POLICE MAN Who Tried to ARREST Ben Shapiro Get’s Totally DESTROYED.

APPLAUDS Break-Out: The Day a University Tried to Arrest Ben Shapiro and Lost the Narrative What happened at DePaul University…

End of content

No more pages to load