Lessons for a Creature of the Forest

I never imagined that teaching a creature from the wilderness to write would force me to confront everything I thought I knew about intelligence, consciousness, and what it truly means to be human.

But when I found those first crude letters scratched into the dirt outside my cabin in the Oregon forests, I realized I had stumbled into something that would challenge not just my understanding of the world, but humanity’s place in it.

My name is Robert Keegan, and in 1994, at fifty‑seven years old, I was exactly where I wanted to be: alone.

After spending three decades as a high school English teacher in Portland, I’d retired early, taken my modest pension, and bought a small cabin on forty acres of dense forest near the town of Estacada. My wife, Linda, had passed away from breast cancer two years earlier, and the house we’d shared in the suburbs had become unbearable—filled with memories that were both precious and painful. Every room echoed with her absence.

The cabin was primitive by most standards. No phone line. Unreliable electricity from an old generator. Water from a well I had to pump by hand. But it had what I needed: solitude, books, and distance from a world that had started to feel too loud, too fast, too complicated.

It was 1994, and while the rest of America was discovering the internet and watching O. J. Simpson’s white Bronco on TV, I was reading Thoreau by lamplight and learning to split firewood without throwing out my back.

The first sign that I wasn’t as alone as I thought came on a cool October morning.

I’d gone out to check my propane tank and found something strange near the tree line: scratches in the dirt that looked almost deliberate. At first, I thought it might be a bear marking territory, but the patterns were too regular, too intentional. They looked like someone had been trying to draw letters, but didn’t quite know how.

I’m a rational man, or at least I thought I was. I’d taught English literature for thirty years, spent my life in the company of books and ideas. I’d never been one for supernatural nonsense or cryptid stories. But standing there, looking at those marks, I felt a chill that had nothing to do with the autumn air.

Over the next week, more marks appeared. Each time, they were closer to the cabin. Each time, they looked a little more like actual letters—crude approximations of H and E and L—as if someone, or something, was trying to spell words without understanding the alphabet.

I should have been frightened.

Instead, I was curious.

Maybe it was the teacher in me. Maybe it was the loneliness that had been my constant companion since Linda died. But I found myself responding.

I took a stick and wrote in the dirt:

HELLO

The next morning, my word was gone, replaced by a shaky attempt at copying it. The letters were backward and uneven, but the intent was unmistakable. Something was trying to communicate.

I set up a simple system. Each morning, I wrote a new word in a cleared patch of dirt near the tree line, always choosing simple, concrete nouns: tree, water, rock, sky. Each night, whatever was out there would attempt to copy them.

The progress was slow, but undeniable.

By the end of the second week, the copies were becoming more accurate.

On November 3rd, 1994, I finally saw what I’d been teaching.

The Student in the Clearing

I’d stayed up late reading Walden, appropriately enough, and dozed off in my chair. Around three in the morning I woke to use the bathroom, and as I passed the window, I caught movement in the moonlit clearing.

Something large was crouched where I’d been writing my lessons.

My first instinct was bear—but the shape was all wrong. Too tall, even when crouching. Too deliberate in its movements.

I watched, frozen, as it used a stick to carefully trace letters in the dirt, its massive hand moving with surprising delicacy.

Then it stood.

In the silver wash of moonlight, I got my first clear look.

It was enormous—at least seven feet tall, maybe more—covered in dark fur that looked almost black in the pale light. Its shoulders were incredibly broad, its arms longer than human proportions would allow. But it was the posture that struck me most: upright, bipedal, unmistakably intelligent in the way it carried itself.

I’d heard the stories, of course. Anyone who’d spent time in the Pacific Northwest had: Bigfoot, Sasquatch, whatever you wanted to call it. I had filed those stories under the same category as UFOs and the Loch Ness Monster: entertaining folklore, nothing more.

But there one was—standing in my clearing, practicing letters like a child learning to write.

The rational part of my brain screamed that this couldn’t be real, that I was hallucinating or dreaming. But I’d been a teacher long enough to recognize a student when I saw one, regardless of species.

The creature finished its practice and melted back into the forest with startling silence for something so large.

At dawn, I went out to examine what it had written.

The word I’d left the previous day was hand. The creature had copied it three times, each iteration slightly better than the last. But it had also added something new: a crude drawing of a hand—five fingers clearly depicted—next to the word.

It was making the connection between symbol and meaning.

I sat heavily on the stump I used for splitting wood, my mind reeling. This wasn’t just mimicry. This was comprehension. Learning. The foundation of language acquisition. In thirty years of teaching, I’d seen this exact progression in countless students.

Never had I imagined seeing it in something that wasn’t human.

The teacher in me took over.

If this creature wanted to learn, I would teach it.

God help me, I would teach it.

Building a Classroom in the Woods

I went back to basics. I built a primitive “classroom” in the clearing: a flat board mounted on two stumps to serve as a writing surface. I used chalk—easier to see than scratches in the dirt. I established a schedule, coming out at dusk when the creature seemed most active.

For the first few sessions, I never saw it directly. I would:

Write words on the board

Leave simple objects beneath:

A rock under the word rock

A pinecone under cone

A metal cup under cup

Then retreat to the cabin

In the morning I’d find the lessons completed, the words copied, sometimes with simple drawings that showed the creature understood the associations.

The breakthrough came on November 18th.

I was at the board, writing the word tree and preparing to head back inside when I heard a low, rumbling vocalization behind me. It vibrated in my chest more than in my ears.

Every hair on my body stood on end.

I turned slowly.

There it was—no more than twenty feet away.

In the fading light, I could see it clearly. The fur was dark brown, not black as I’d first thought, streaked with gray around what passed for a face. The features were somewhere between human and ape, but fully neither: a flatter face than a gorilla, a more prominent brow than a human. But it was the eyes that held me—dark, attentive, undeniably intelligent, watching me with cautious curiosity.

“Hello,” I said, my voice shaking. “I’m Robert. I’ve been leaving these lessons for you.”

The creature made another sound—softer this time—and took a step closer.

This was a predator, I reminded myself. Something that could kill me effortlessly if it chose to. But it was also a student.

And I had never in my life turned away a student who wanted to learn.

It approached the board slowly, always keeping me in its peripheral vision. When it reached the chalk, it picked it up with surprising delicacy. Those massive hands handled the small piece of chalk as carefully as I might hold a fragile glass ornament.

It looked at me, then at the board, then back at me—as if asking permission.

I nodded and stepped back.

The creature wrote. The letters were shaky and uneven, but clear:

TREE

“Yes,” I said, my throat tightening. “That’s right. That’s very good.”

It made a sound that might have been pleasure.

Then it pointed at itself.

It was asking what it was called. What its word was.

I thought about the names humans had invented for beings like this: Bigfoot, Sasquatch—half joke, half monster. This creature deserved better than that. It deserved to name itself. But first, it needed more language.

“Not yet,” I said gently. “First you learn. Then you choose your name. Understand?”

It tilted its head, considering. Then it nodded—a thoroughly human gesture that sent another shiver down my spine.

From that day on, we were no longer just mysterious signs in the dirt and anonymous lessons on a board.

We were teacher and student.

Words, Sentences, and the First Questions

In the weeks that followed, we established a routine.

He—by then I could tell he was male—arrived most evenings at dusk. We worked on:

Basic vocabulary

Verb tenses

Simple pronouns

Short sentences

His handwriting, while large and somewhat awkward, quickly became legible. By December, we were having simple written conversations.

One cold evening, I wrote:

WHERE DO YOU LIVE?

He responded:

TREES. MOUNTAINS. ALONE.

That last word hit me harder than I expected.

I knew loneliness. My isolation had been a choice, a retreat from people and noise. His loneliness was something else entirely—existential, species-deep. He might be the last of his kind.

I asked:

ARE THERE OTHERS LIKE YOU?

He took a long time before answering:

DON’T KNOW. MAYBE LONG AGO.

That night, I lay awake, staring at the dark ceiling of the cabin. If there had once been others, but there weren’t anymore—if he had lost them, or simply outlived their memory—then I might be teaching the last of his species to read and write.

The responsibility felt crushing.

Christmas approached, and I did something I hadn’t done since Linda died.

I decorated.

Nothing elaborate—just a small tree in the cabin and some colored lights powered by the generator. When my student arrived for his lesson, he stopped at the edge of the clearing, staring at the soft glow through the cabin window.

I wrote on the board:

HOLIDAY. CELEBRATION. LIGHT IN DARKNESS.

He approached the window, mesmerized. Colored light reflected in his dark eyes. After a moment, he turned to the board and wrote:

BEAUTIFUL. THANK YOU.

In that moment, it struck me: this impossible creature and this lonely old man were building something that transcended species.

We were building a bridge.

But with that connection came questions I wasn’t prepared for.

When a Student Starts Asking Why

January 1995 arrived with heavy snowfall that smothered the forest in white. The cold didn’t bother him. It bothered me a great deal.

Our curriculum had advanced. I’d brought out an old portable chalkboard and boxes of colored chalk. He showed a definite preference for white and blue. We’d moved beyond nouns into:

Verb tenses (past, present, future)

Differences between want vs need

Know vs understand

Then, on January 15th, everything changed.

I wrote:

QUESTIONS HELP US LEARN.

WHAT QUESTIONS DO YOU HAVE?

I expected grammar questions. Maybe a vocabulary request.

He stared at the board for a long time, then wrote:

WHY DO HUMANS CUT DOWN TREES?

I stood there with the chalk in my hand, suddenly aware that language lessons had turned into something deeper.

This wasn’t vocabulary anymore.

This was ethics.

FOR WOOD,

TO BUILD HOUSES,

TO MAKE PAPER,

TO CLEAR LAND FOR FARMS AND CITIES,

I wrote.

He read, then responded:

BUT TREES ARE HOME.

FOR BIRDS, FOR DEER, FOR ME.

WHY IS HUMAN HOME MORE IMPORTANT?

How do you explain human exceptionalism to someone who lives in the forest and experiences firsthand how everything depends on everything else?

I wrote:

HUMANS THINK THEY ARE MOST IMPORTANT.

NOT ALL HUMANS, BUT MANY.

He studied that, then wrote:

IS THAT TRUE?

ARE HUMANS MOST IMPORTANT?

I hesitated.

I DON’T KNOW, I wrote.

WHAT DO YOU THINK?

He took a long time with this one. Then:

ALL THINGS ARE IMPORTANT.

TREE IMPORTANT TO BIRD.

BIRD IMPORTANT TO FOREST.

HUMAN IMPORTANT TO HUMAN.

ME IMPORTANT TO ME.

NO ONE MOST IMPORTANT.

In a few simple lines, he’d articulated a philosophy that ecologists and philosophers had struggled to name and defend: intrinsic value, interdependence, the rejection of a single privileged species.

THAT’S VERY WISE, I wrote.

WHAT IS WISE? he asked.

UNDERSTANDING TRUTH. SEEING CLEARLY. THINKING DEEPLY.

He seemed pleased by that.

Then he wrote:

YOU ARE WISE. YOU TEACH ME.

WHO TEACHES HUMANS?

I had no satisfying answer.

Seeing Humanity from the Outside

Through February and March, his questions deepened.

He asked:

Why humans fought wars when wars brought only suffering.

Why humans kept some animals as pets and ate others.

Why humans lived in boxes instead of under the open sky.

Every question pushed me to look at my own species with the eyes of an outsider—and I didn’t always like what I saw.

I began keeping a journal of our lessons. Not just his words, but his posture, his hesitations, the progression of his thinking. I had the odd sense that I was documenting first contact between two intelligent species.

His reading level skyrocketed.

Children’s books lasted him days.

Young adult novels lasted him weeks.

By late February, he was reading Steinbeck and Jack London.

I gave him Of Mice and Men. When he finished, he wrote:

WHY DID GEORGE KILL LENNIE IF THEY WERE FRIENDS?

We spent an hour writing back and forth about mercy, impossible choices, and love. He finally wrote:

DEATH IS ALWAYS WORSE.

LIFE IS BETTER EVEN IF HARD.

DO YOU REALLY BELIEVE THAT? I asked.

YES.

IF LIFE IS PAIN AND SUFFERING, IT IS STILL LIFE.

STILL CHANCE FOR CHANGE.

DEATH IS END. NO CHANCE.

His commitment to life, even difficult life, made me rethink assumptions I’d held for years.

On Progress, Principles, and Hypocrisy

Spring and summer of 1995 brought warmth and wildflowers—and a sharper edge to his observations.

I made regular trips to Portland for books: philosophy, history, anthropology, poetry, environmental science. The cashiers must have thought I was preparing for an exam the world didn’t know about.

He read everything.

He was deeply troubled by:

Logging in the Pacific Northwest

The Holocaust

Slavery and the founding contradictions of the United States

On the Holocaust, after reading several accounts, he wrote:

6 MILLION JEWS KILLED.

MILLIONS MORE HUMANS KILLED HUMANS.

NOT FOR FOOD. NOT FOR LAND.

FOR HATE. FOR IDEOLOGY.

WHAT IS IDEOLOGY WORTH 6 MILLION LIVES?

I had taught that history for decades, but explaining it to someone who could not fathom such hatred made it feel freshly monstrous.

IF HUMANS CAN DO THIS TO HUMANS, he wrote,

WHAT WOULD HUMANS DO TO ME?

I wanted to reassure him.

I couldn’t.

SOME HUMANS WOULD WANT TO PROTECT YOU, I wrote.

SOME WOULD WANT TO STUDY YOU.

SOME WOULD WANT TO PROFIT FROM YOU.

SOME WOULD WANT TO KILL YOU OUT OF FEAR.

I DON’T KNOW WHICH GROUP WOULD WIN.

THAT IS WHY I STAY HIDDEN, he replied.

On American history, after reading about the Declaration of Independence, he wrote:

UNITED STATES SAYS “ALL MEN ARE CREATED EQUAL.”

MEN WHO WROTE THIS OWNED SLAVES.

HOW?

I explained the standard textbook answers. He dismissed them in one line:

THEN PRINCIPLES ARE NOT PRINCIPLES.

IF YOU ONLY FOLLOW THEM WHEN EASY, THEY ARE PREFERENCES.

I sat with that for a long time.

He wrote extended reflections that I copied into notebooks. One I titled On Human Progress:

HUMANS ARE PROUD OF “PROGRESS.”

HUMANS POINT TO CITIES AND MACHINES AND TECHNOLOGY.

BUT WHAT IS PROGRESS?IS CUTTING DOWN ANCIENT FOREST TO BUILD PARKING LOT PROGRESS?

IS DAMMING RIVER SO SALMON CANNOT SPAWN PROGRESS?

IS FILLING AIR WITH SMOKE PROGRESS?HUMANS MEASURE PROGRESS BY WHAT THEY BUILD.

HUMANS DO NOT MEASURE WHAT THEY DESTROY.MAYBE TRUE PROGRESS IS HOW MUCH YOU LEAVE ALONE.

HOW MANY OLD TREES STILL STAND.

HOW MANY GENERATIONS OF SALMON STILL RUN.BY THAT MEASURE, HUMANS ARE NOT ADVANCED.

HUMANS ARE GOING BACKWARD.

“You should publish this,” I told him. “People need to read it.”

HUMANS WOULD NOT LISTEN TO ME, he wrote.

THEY WOULD ONLY WANT TO CAPTURE ME. STUDY ME.

MAYBE YOU WRITE IT. SAY IT IS YOUR WORDS.

“That would be dishonest,” I protested.

WHICH IS MORE IMPORTANT? he asked.

TRUTH ABOUT WHO WROTE WORDS, OR HUMANS HEARING TRUTH IN WORDS?

I had no satisfying answer.

Rumors, Suspicion, and a Name

June 1995 brought trouble of a more mundane kind.

Tom Brewster, my nearest neighbor three miles down the logging road, came by.

“Bob, people in town are talking,” he said. “Books you’re buying. Chalkboards. Weird noises at night. Jerry says he heard another voice up here. And not a human one.”

“Jerry is drunk more than sober,” I said, too quickly.

“Maybe. But I made a promise to Linda I’d look out for you. If you’re messing with something dangerous, these woods won’t keep secrets forever.”

When he left, I realized how careless I’d been. The forest might hide a lot—but not everything.

That night, I told my student.

MAYBE WE SHOULD STOP, he wrote.

LESSONS TOO DANGEROUS FOR YOU.

NO, I answered.

YOU HAVE A RIGHT TO LEARN. I WON’T TAKE THAT AWAY BECAUSE PEOPLE GOSSIP.

By late summer, his thoughts turned toward loneliness and connection. In one piece I later titled On Human Loneliness, he wrote:

HUMANS LIVE IN CITIES WITH MILLIONS OF OTHER HUMANS.

YET HUMANS ARE LONELY. THEY TAKE PILLS FOR SADNESS.

THEY PAY OTHER HUMANS TO LISTEN TO FEELINGS.I AM ALONE. MAYBE LAST OF MY KIND.

BUT I AM NOT LONELY LIKE HUMANS.

I AM CONNECTED TO FOREST, TO DEER WHO DRINK FROM STREAM,

TO OWL WHO HUNTS AT NIGHT, TO TREES THAT GIVE SHELTER.HUMANS LIVE WITH MILLIONS BUT ARE DISCONNECTED.

DISCONNECTED FROM EARTH, FROM ANIMALS, FROM EACH OTHER.HUMANS HAVE FORGOTTEN HOW TO BE PART OF WORLD.

HUMANS THINK THEY ARE ABOVE WORLD.

THAT IS WHY HUMANS ARE LONELY.

He was, in his way, diagnosing modern alienation from a forest clearing.

By autumn, I’d filled three notebooks with his writing. I asked him one evening:

WHAT DO YOU WANT ME TO DO WITH YOUR WORDS?

He considered, then wrote:

THEY ARE NOT “MY” WORDS. THEY ARE TRUTHS.

TRUTH DOES NOT BELONG TO ANYONE.

IF HUMANS NEED THESE TRUTHS, SHARE THEM.

SAY THEY ARE FROM AN OBSERVER, AN OUTSIDER.

I DO NOT NEED CREDIT. I NEED HUMANS TO LISTEN.

I asked him then:

DOES THIS MAKE YOU HATE US?

He took a long time to respond:

NO. I DO NOT HATE HUMANS.

I AM DISAPPOINTED IN HUMANS.

HUMANS HAVE SUCH POTENTIAL FOR BEAUTY, CREATION, LOVE.

BUT HUMANS CHOOSE SMALL. CHOOSE SELFISH.

THAT IS NOT HATRED. THAT IS SADNESS.BUT IT IS NOT TOO LATE.

I CHANGED THROUGH LEARNING. HUMANS CAN TOO.

THAT IS WHY EDUCATION MATTERS.

THAT IS WHY YOU WERE TEACHER.

I’d spent thirty years teaching teenagers. It was this non‑human student who restored my faith in the profession.

Sometime near the end of that year, without fanfare, he chose a name.

I didn’t ask for it. He simply wrote one evening:

I AM MOSS.

It suited him perfectly: quiet, old, rooted in shadow and damp, clinging stubbornly to life on the old stones of the world.

Age, Illness, and the Coming Net

By late 1995, I was seventy‑eight. My body had begun to betray me.

Chest pains. Shaking hands. Shortness of breath. He noticed everything.

YOU ARE NOT WELL, Moss wrote one evening as I arrived late and winded.

I’M OLD, I wrote. THIS IS WHAT HAPPENS.

YOU SHOULD SEE DOCTOR.

DOCTORS ASK QUESTIONS, I replied.

QUESTIONS I CANNOT ANSWER WITHOUT LYING.

YOU ARE IMPORTANT TO ME, he wrote bluntly.

IF YOU DIE, I WILL BE ALONE AGAIN. MORE ALONE THAN BEFORE.

NOW I KNOW WHAT CONNECTION IS.

He was right about that difference: once you’ve known connection, returning to solitude is not a neutral state. It is loss.

As October deepened, I made a decision.

I would attempt to publish some of his essays.

I carefully edited them—retaining his thought, smoothing only the language that betrayed his unique vantage point too clearly. I framed them as the reflections of “an outside observer of human civilization” and sent them to philosophy journals and magazines under my own name.

The rejections came quickly.

Too unconventional

Too idealistic

Too critical of human civilization

Not sufficiently scholarly

One editor wrote:

“These essays read as though they were written by someone who has never lived in human society. They are too idealistic, too unacquainted with the compromises reality demands.”

I showed that letter to Moss.

He read it and wrote:

EDITOR IS RIGHT. I HAVE NEVER LIVED IN HUMAN SOCIETY.

THAT IS WHY I SEE WHAT YOU CANNOT SEE.

OUTSIDER SEES MORE CLEARLY.

He was not insulted.

He was amused.

In early November, everything changed again.

Dr. Cartwright and the Tightening Circle

One cold afternoon, I heard a truck on the logging road. By the time I got to the clearing, a woman in her early forties was stepping out.

“Mr. Keegan? I’m Dr. Helen Cartwright from Oregon State University. I’m conducting a survey of large mammal populations in this region. Do you have a few minutes?”

She declined coffee, but accepted a place on the porch.

“We’ve been finding unusual evidence in this area,” she said. “Game camera images that don’t match known species. Hair samples with anomalous primate DNA. Reports from hikers seeing something large and bipedal.”

“Bears can look bipedal from certain angles,” I said.

“We thought so too,” she replied. “But the stride length is wrong. And the footprints don’t match humans or bears.”

She was too close. Too calm. Too methodical.

“We’d like permission to place camera traps along your property line.”

“No,” I said immediately.

She looked surprised, then wary.

“I came out here for privacy,” I said. “I won’t have cameras on my property.”

She studied me, then nodded slowly.

“If you see anything unusual, call me. Please.”

After she left, my hands shook so badly I could barely light the lamp.

That night, I told Moss everything. He had already seen her from the forest.

SHE IS DANGEROUS, he wrote.

SMART. SHE KNOWS ENOUGH TO GET MORE.

I asked where they might have found his DNA.

HAIR ON BARK, he admitted. SOMETIMES I SCRATCH ON TREES.

We both realized the same thing at once.

He couldn’t remain a rumor forever.

In December, Tom came by again with worse news.

“That professor? Cartwright? She’s got funding now. Big project. Starting in spring. Grids of cameras. Survey teams. Drones with thermal imaging. If there’s something out here, they’re going to find it.”

“Why are you telling me this, Tom?”

“Because whatever you’re hiding, you need to decide how this ends before someone else decides it for you.”

That night, standing under the bare, black branches, I told Moss:

THEY’LL HAVE DRONES BY SPRING. THERMAL CAMERAS. YOU CAN’T HIDE FROM THOSE FOREVER.

HOW LONG? he asked.

FOUR OR FIVE MONTHS.

He stared into the dark forest for a long time.

THEN WE DECIDE HOW STORY ENDS, he wrote.

OR HOW IT BEGINS.

A Choice: Hiding or Personhood

January 1996 brought brutal cold and a deadline.

We spent nights at the board, planning. Moss asked:

WHAT HAPPENS IF I REVEAL MYSELF? EXACTLY. STEP BY STEP.

I laid out what I could imagine:

-

We choose the terms.

Not a chance encounter. A controlled introduction.

We gather allies first.

An ethical scientist

A bioethicist

A civil rights lawyer

A journalist known for integrity

We present documentation.

His writings. His progress. His philosophical reflections.

We demand protections.

No captivity

No invasive research without consent

Legal recognition of personhood

WOULD THAT WORK? he asked.

I DON’T KNOW, I answered honestly.

BUT IT’S BETTER THAN BEING DISCOVERED AS A SPECIMEN.

WHAT IF HUMANS REFUSE?

THEN WE FIGHT, I wrote.

IN COURT. IN THE PRESS. IN PUBLIC.

WE FORCE HUMANITY TO ANSWER WHETHER BEING HUMAN IS REQUIRED FOR PERSONHOOD.

YOU ARE OLD, Moss wrote.

YOU ARE SICK. CAN YOU FIGHT THAT FIGHT?

I CAN TRY, I wrote.

FOR AS LONG AS I HAVE.

He stared at the board for a long time.

On January 28th, the decision was forced.

When I returned from town, Dr. Cartwright was waiting on my porch—with photographs of fresh, enormous footprints in the snow crossing my land.

“These match every other anomalous print we’ve found,” she said. “They’re all over your property. Mr. Keegan, something is here.”

I watched her carefully, then asked:

“What if I told you that what you’re looking for isn’t a what, but a who?”

Her eyes sharpened.

“Are you saying—?”

“I’m asking a hypothetical,” I said. “If you encountered a being that could think, feel, and communicate—a non‑human person—would you treat it as an animal, or as a person?”

She didn’t answer immediately.

“That would raise profound ethical questions,” she said at last. “About rights. About research. About responsibility.”

“And how would you answer them?”

“I’d like to think I’d put ethics before curiosity,” she said. “But I know there would be pressure.”

I asked her, plainly:

“If such a being wanted to reveal itself on its own terms, with conditions and protections, could you help? Could you bring in people who would treat it as a subject with rights, not a specimen?”

“You’re asking me to put ethics before science,” she said quietly.

“Yes.”

She held my gaze, then nodded.

“Yes. I would try. But I’d need proof. And I’d need help from others—bioethicists, legal experts. This can’t just be you and me.”

After she left, I told Moss everything.

He listened in silence. Then wrote:

SHE KNOWS. OR ALMOST KNOWS.

DOOR IS OPEN.

I’M SORRY, I wrote. I MADE A DECISION FOR YOU.

NO, he answered. TIME MADE DECISION.

WHAT ARE CHANCES THIS GOES WELL?

MAYBE FIFTY–FIFTY, I said.

DOING NOTHING IS ZERO.

He stared at the snow‑covered ground for a long time.

ALL MY LIFE I HAVE BEEN HIDING, he wrote.

SAFE, BUT NOT LIVING.

YOU TAUGHT ME CONNECTION MATTERS.

ISOLATION IS NOT SAME AS SAFETY.I AM AFRAID. BUT I AM TIRED OF HIDING.

IF THERE IS CHANCE HUMANS SEE ME AS PERSON, I WANT TO TRY.

ARE YOU SURE? I asked.

NO.

BUT I AM DECIDED.

WE DO THIS ON OUR TERMS.

Moss Steps into the Human World

Over the next three weeks, we planned.

I called Dr. Cartwright and said we were ready—with strict conditions:

She would bring:

A bioethicist

A civil rights attorney

A journalist with a reputation for integrity

All would sign non‑disclosure agreements

They would agree in writing:

Moss was not a “specimen”

No photography, no samples, no testing without consent

The meeting’s purpose was to consider his rights and protection

She agreed.

The night before the meeting, Moss came into the cabin for the first time. He ducked under the doorway, filling the small space with fur and cold air and the faint scent of earth and pine.

By lamplight, he looked both more frightening and more vulnerable than he ever had outside.

ARE YOU FRIGHTENED? I asked.

YES, he wrote.

BUT ALSO HOPEFUL.

WHAT IF THEY DO NOT SEE YOU AS A PERSON?

THEN WE MAKE THEM SEE, I said.

WITH YOUR WORDS. YOUR THINKING. YOUR TRUTH.

He hesitated, then wrote:

WHATEVER HAPPENS, THANK YOU.

FOR TEACHING ME. FOR SEEING ME. FOR BEING FAMILY.

EVEN IF THIS ENDS BADLY, IT WAS WORTH IT.

“You were worth it,” I said, my voice rough. “Every risk.”

On the morning of February 22nd, 1996, four vehicles came up the logging road.

Dr. Helen Cartwright, wildlife biologist

Dr. James Morrison, bioethicist from Stanford

Sarah Chen, civil rights attorney

Marcus Webb, journalist

We met on the porch. I explained:

“You are not here to witness a discovery. You’re here to meet someone. You’re not researchers today. You’re potential allies.”

Dr. Morrison said solemnly, “We understand. If this being can communicate and reason, we treat him as a person with agency.”

“Him?” Sarah asked.

“Him,” I confirmed. “He’s male. He’s intelligent. And he is very afraid of you.”

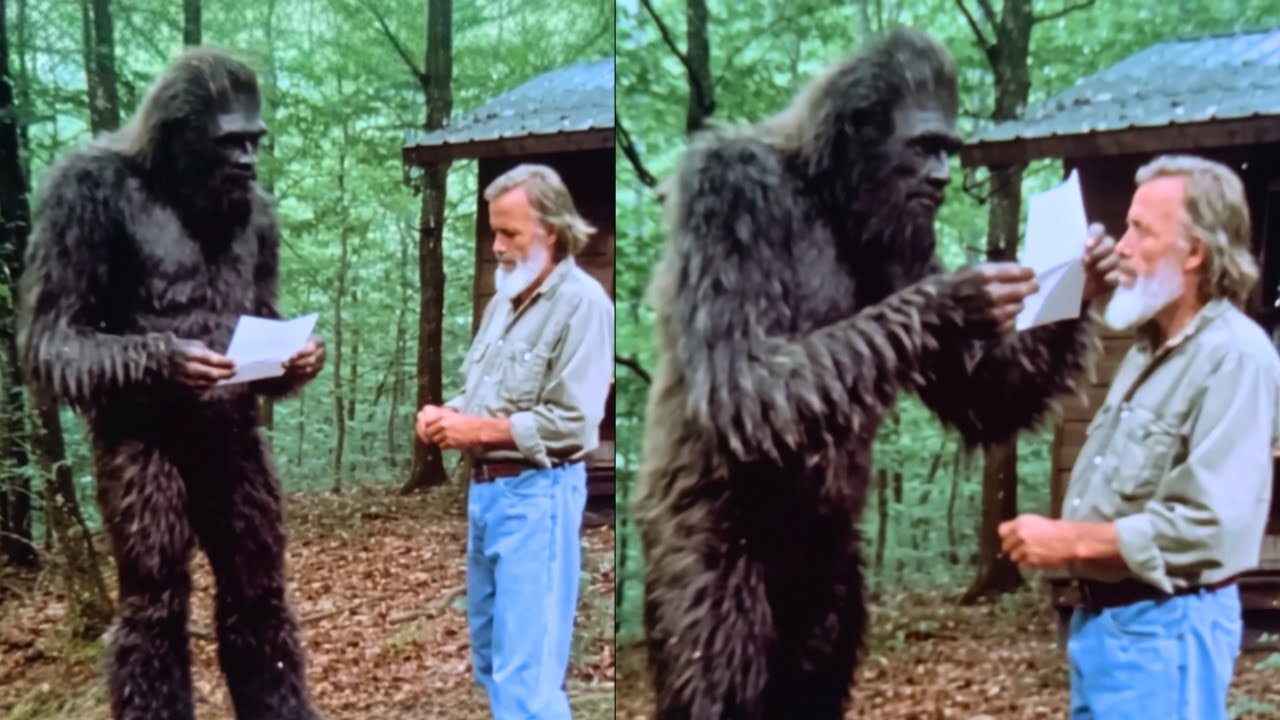

I turned toward the trees and gave the agreed signal: a specific sequence of knocks on the board.

For a moment, nothing happened.

Then Moss stepped out of the forest.

He walked upright into the clearing, seven feet eight inches of fur and muscle and thought. No one screamed. No one ran. To their credit, no one reached for a camera.

He picked up the chalk and wrote on the board, with careful strokes:

MY NAME IS MOSS.

I AM PLEASED TO MEET YOU.

The name surprised them. It had surprised me once, too.

“Hello, Moss,” Dr. Morrison said, his voice steady but thick. “My name is James. It’s an honor.”

One by one, they introduced themselves. Moss wrote each name down, pronouncing rough approximations in a low, gravelly voice that carried startling warmth.

He turned back to the board.

MR. KEEGAN TAUGHT ME TO READ AND WRITE.

I HAVE LEARNED ABOUT HUMANITY.

NOW I WANT TO SHARE WHAT I HAVE LEARNED.

BUT I AM AFRAID.

“Afraid of what?” Sarah asked gently.

He wrote:

AFRAID HUMANS WILL NOT SEE ME AS PERSON.

WILL SEE ONLY ANIMAL.

WILL WANT TO PUT ME IN CAGE.I HAVE LIVED FREE ALL MY LIFE.

I DO NOT WANT TO LOSE THAT.

Sarah nodded slowly. “We’re here to help you keep that freedom. But I have to be honest: this will be complicated. Human law doesn’t have much room yet for non‑human persons.”

I UNDERSTAND, Moss wrote.

ALTERNATIVE IS WORSE.

ALTERNATIVE IS BEING FOUND BY HUMANS WHO DO NOT ASK WHAT I WANT.

I CHOOSE THIS RISK.

Over the next four hours, they questioned him—not as an object, but as a mind.

He:

Read aloud from books

Summarized arguments

Wrote his own analyses of human history, progress, cruelty, and beauty

Answered questions about his own experiences and fears

They saw what I had seen: an intelligence fully aware of itself and the stakes.

“This meets every criterion for personhood I’ve ever studied,” Dr. Morrison said at last, closing my notebooks with trembling hands. “Cognitive complexity, self‑awareness, moral reasoning, the capacity for long‑term planning, for suffering, for hope.”

“Can you help him?” I asked.

He looked at Moss, not at me.

“Yes,” he said. “We can try. It will be hard. But your own words, Moss, are your strongest case.”

Marcus, the journalist, asked:

“Moss, would you be willing for your observations about humanity to be published? The world needs to hear your perspective.”

Moss looked at me, then wrote:

YES. BUT NOT YET.

FIRST, WE ESTABLISH THAT I AM PERSON.

THEN WE SHARE WHAT THIS PERSON THINKS.

ORDER MATTERS.

Sarah smiled, despite herself.

“He’s right,” she said. “If we lead with his critique of humanity, people will feel attacked and dismiss him. If we establish his personhood first, his words become harder to ignore.”

By evening, we had the outline of a plan:

Three months of preparation

Sarah drafts legal filings for a landmark case: Moss v. State, or something like it.

Dr. Morrison writes an ethical position paper on non‑human personhood using Moss as a central case.

Dr. Cartwright documents his existence scientifically without reducing him to a specimen.

Marcus prepares a long‑form investigative piece, to be released only after Moss’s legal status is filed.

A coordinated revelation

Press conference, with Moss choosing whether to appear directly or only through his writing.

Immediate legal action seeking protective status.

Ethical frameworks presented alongside biological evidence.

Not “Bigfoot Discovered.”

But: A Person Outside Our Species: The Case of Moss.

That night, after they left, the forest felt very quiet. Moss and I sat side by side on the porch.

HOW DO YOU THINK IT WENT? he asked.

BETTER THAN I HOPED, I said.

THEY SAW YOU.

BECAUSE YOU TAUGHT ME, he wrote.

YOU GAVE ME WORDS.

YOU GAVE ME WAY TO PROVE I AM MORE THAN BODY.

“You were always more than a body,” I said. “All I did was give you chalk.”

He made a low, familiar sound deep in his chest. I had come to recognize it as something like laughter.

The future beyond that night remains unwritten.

But I know this much:

In a small clearing in the Oregon woods, a retired human teacher and a solitary giant named Moss proved something that may matter more than any court case or headline.

Personhood isn’t about species.

It’s about the capacity to learn, to question, to suffer, to hope, and to care.

And sometimes, it’s about two lonely beings finding each other in the dark and choosing, against every instinct for safety, to step into the light together.

News

“Not All Cultures Are Equal”: Republican Stuns CNN Panel With Blunt Defense of Border Security and Critique of Ilhan Omar

“Not All Cultures Are Equal”: Republican Stuns CNN Panel With Blunt Defense of Border Security and Critique of Ilhan Omar…

He’s Met Bigfoot Since the 70s. What It Told Him About Humans Will Shock You!

The Last Friend in the Cascades How a Widower Spent 25 Years Learning from Bigfoot I’m 97 years old, and…

Here’s What Bigfoot Does with Human Bodies

Three Knocks in the Timber: A Bigfoot Haunting in Idaho I know this is going to sound insane, but it’s…

Unseen Forces: Zak Bagans Hospitalized After Uncut Ghost Adventures Investigation Leaves Team and Fans Shaken

Unseen Forces: Zak Bagans Hospitalized After Uncut Ghost Adventures Investigation Leaves Team and Fans Shaken Breaking News: The Night That…

“10 American Citizens Deported?” Alyssa Slotkin Demands Answers and Exposes Border Overreach

“10 American Citizens Deported?” Alyssa Slotkin Demands Answers and Exposes Border Overreach The Confrontation: Slotkin Demands the Truth In a…

Blake Shelton DESTROYS Joy Behar LIVE on The View After Explosive Clash Shocks Hollywood!

Blake Shelton vs. Joy Behar: The Day Country Met Confrontation and America Chose Sides Setting the Stage: A Routine Morning…

End of content

No more pages to load