Why Giants Vanished After 1800 — The Mudflood Cover-up

The Doorways That Remembered

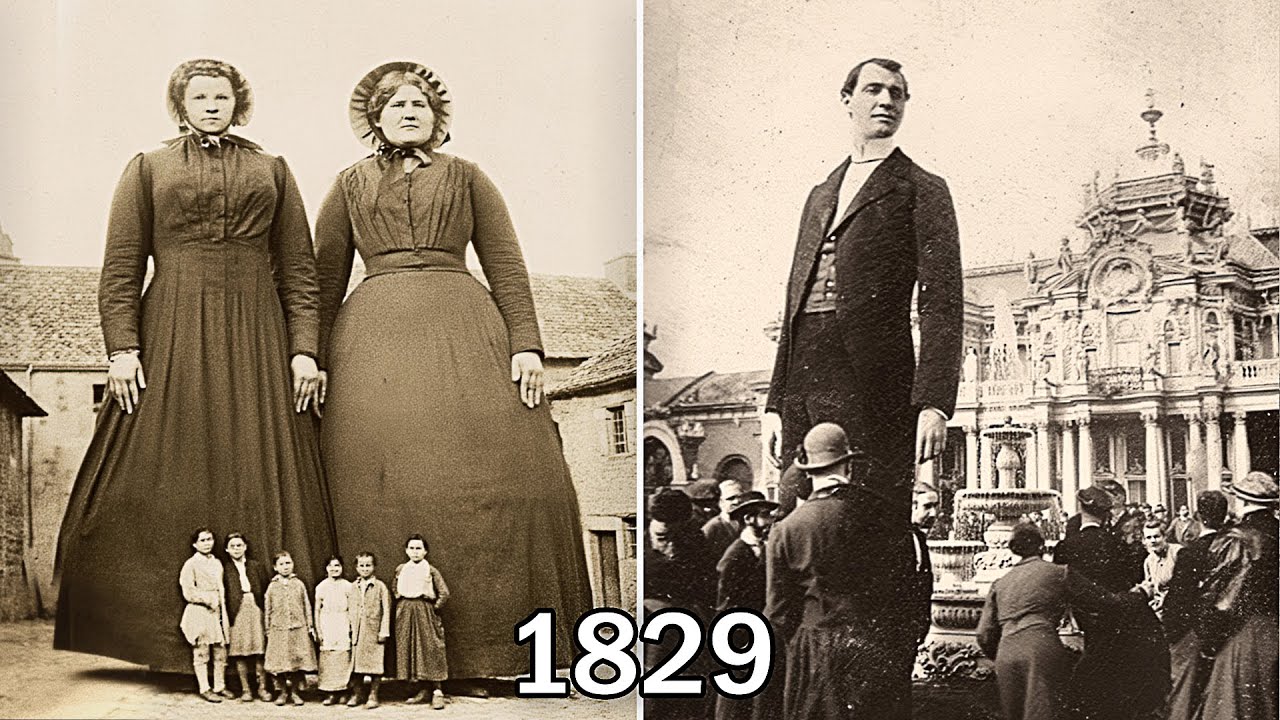

The first time Mara Vance saw a “giant,” she didn’t believe it was a giant at all. She believed it was what she’d been trained to believe: a trick of lens, a staged curiosity, a Victorian carnival exaggeration pinned to paper and marketed as truth. The kind of thing that thrived in the margins of history—where fact and spectacle shook hands and pretended they were friends.

But the photograph wasn’t a carnival portrait. It wasn’t labeled with flamboyant ink or framed by velvet curtains. It was a plain albumen print tucked in a municipal archive box that smelled like dust and old glue. The caption, typed on a fading strip of paper, was boring to the point of cruelty:

“Waterworks Crew, East Gate Station, 1878.”

Seven men stood in front of a brick building with an arched doorway. Six looked ordinary. The seventh looked… wrong.

Not monstrous. Not grotesque. Just tall—tall in a way that made Mara’s eyes try to correct it, as if the brain could fix the world by insistence. The man’s shoulders sat near the midpoint of the arch. His hands, relaxed at his sides, were the size of spades. His face held no pride at being remarkable. He wore the same work shirt as the others. The same grime. The same exhausted neutrality of someone who’d rather be home.

Mara leaned closer. The doorway wasn’t just large—it was designed large. The brickwork was careful. The stone threshold was worn like it had been walked across for decades. If it was a stage set, it was an absurdly expensive one.

She pulled out her notebook and wrote, without meaning to make it sound like a confession:

If he’s a trick, the building has to be in on it.

That night, she told herself she’d forget it.

Two days later, she requested every photograph in the archive tagged with any of the following: waterworks, rail crews, foundries, municipal halls, orphanages, hospitals, barracks, and “new construction.” It was a wide net, the kind researchers cast when they’re pretending they aren’t hunting one specific animal.

By the end of the week, her desk looked like a small paper storm had settled on it. And the storm had a pattern.

There were more tall figures than there should have been—too many to be dismissed as rare medical outliers. In group shots. In street scenes. In factory yards. Not posed like attractions, but placed like neighbors. Men and women who were tall enough that doorways looked apologetic around them, tall enough that stair risers seemed designed for a longer stride.

And then, with the clean brutality of a line drawn by someone with power and a ruler, the tall figures stopped appearing.

Not gradually. Not with a tapering of frequency. They vanished from the photographic record as if a switch had been flipped.

Mara had studied wars. She knew how bodies disappeared in wars. She knew how famine and plague and forced migration tore holes in populations and left records like scars—spikes in mortality logs, panicked letters, mass graves, bitter songs.

This disappearance left no scar she could easily name.

It left a smoothness. A silence.

And silence, Mara had learned, often meant someone had been paid—or threatened—to keep it.

I. The Basement Windows

Mara’s job title at Halden University was crisp and respectable: associate professor of nineteenth-century urban development. It sounded like clean shoes and tidy footnotes. In reality, it meant crawling through municipal basements with a headlamp, photographing foundation stones while spiders expressed their opinions.

The city of Larkhaven—her current research site—was proud of its “Old Quarter,” a loop of grand stone buildings with domes and pillars and ornamental ironwork that looked slightly too ambitious for a coastal town that had once relied on fishing and timber.

Tour guides called the architecture “neo-classical,” because that label solved questions the way a rug solves dust: by covering it.

Mara had walked those streets a thousand times. She had admired the buildings the way anyone admired old things: with affection and a gentle assumption that they were comprehensible.

Now she couldn’t stop staring at the windows.

Half-buried windows.

Windows that began at sidewalk level and extended down into shadow, as if the building had tried to inhale the street and gotten stuck.

In front of the Old Quarter courthouse, Mara crouched and traced the stone lip where glass met masonry. The frame was too elegant for a basement. The molding had been carved with care. This wasn’t a storage cellar window. It had been meant for light.

The street didn’t match the building.

She stood and looked along the facade. The main entrance doors were enormous—double doors within a monumental arch. They weren’t just tall. They were tall in the same precise way the arched doorway in the crew photograph had been tall: not ostentatious, not wasteful, but functional.

As if someone once needed to pass through them without bowing.

Her phone buzzed. A message from Cal Mercer, the city engineer who had agreed—after three weeks of polite resistance—to show her the old infrastructure maps.

Cal: You free? I can do 20 minutes in the basement of East Gate Station before my next meeting. Bring boots. And maybe a tetanus shot.

Mara typed back: On my way.

East Gate Station was where she’d found the photograph. In the present day it housed a cheerful museum with interactive displays about clean water and civic pride. Families brought children there to press buttons and watch miniature pumps run.

The basement tour wasn’t on the brochure.

Cal met her at a staff door and led her down a narrow staircase. The air cooled. The museum’s bright chatter faded into a damp hush. In the basement corridor, pipes ran like thick veins. The walls were rough stone, older than the brick upstairs.

Cal stopped beside a heavy metal hatch set into the floor.

“This,” he said, “is why I don’t sleep.”

He pulled the hatch open. A smell rose—wet earth, old minerals, and something faintly metallic, like pennies.

Below was a cavity that looked like the mouth of a tunnel. Mara crouched and shined her headlamp in.

A corridor extended into darkness. Its ceiling was high enough that Cal could stand in it. But the corridor wasn’t built for Cal. Its proportions were… generous. The floor was worn smooth by traffic. The side walls had grooves at shoulder height, like rails or handholds.

And along the right wall, every few feet, were metal mounts—brackets designed to hold something heavy. Something long.

“Old conduit?” Mara asked.

Cal shrugged. “No record. The city’s archive says this was sealed after the Flood Year.”

“The flood,” Mara repeated.

Everyone in Larkhaven knew the story: in 1889, after weeks of rain, the river swelled and the lower district was inundated with mud and debris. There were photographs of wagons half-buried, men digging out storefronts, a mayor posing with a shovel for morale.

A disaster. A civic trauma.

But Mara had read enough firsthand accounts to notice something odd. The flood was described like a single event, yet the consequences looked like a deliberate change in ground level. Streets were raised. First floors became basements. New sidewalks were laid over old thresholds.

People talked about rebuilding, but the “rebuild” often looked like adaptation—like survivors had inherited an environment already half-changed.

Mara looked back at the tunnel.

“How far does it go?” she asked.

Cal’s mouth tightened. “We don’t know. It’s not on modern schematics. If my team found this during a project, we’d call it a hazard and fill it. Easier.”

“Easier,” Mara echoed.

Cal looked at her, and for a moment she saw the strain beneath his professionalism—the city engineer caught between curiosity and liability.

“You’re not the first person to ask questions,” he said quietly. “You’re just the first with tenure.”

Mara smiled despite herself. “So there have been others.”

“A guy came by five years ago,” Cal said. “Said he was an independent researcher. Claimed these tunnels connected to ‘old world’ systems. Said the buildings were machines.”

“And you believed him?”

Cal paused. “I believed he was annoying. But sometimes annoying people are the only ones paying attention.”

Mara leaned closer to the hatch. In the beam of her headlamp, something glinted on the wall—an embossed plate, green with age.

She climbed down two steps and brushed grime off the plate with her glove. Letters emerged, in a serif script so formal it felt like a bow.

HALDEN & CO. REGULATOR CHAMBER AUTHORIZED OPERATORS ONLY

Regulator. Not conduit. Not storage. Chamber.

“Authorized operators,” Mara murmured, and the words felt like an invitation and a warning.

Cal cleared his throat. “Ten minutes, Professor.”

Mara climbed back up. But she didn’t stop thinking about the word operators all day.

Not builders. Not owners. Operators.

Someone had built systems meant to be run.

And someone had stopped running them.

II. The Glass Plates

Mara’s colleague in the photography department was a man named Jonah Sato, a quiet technician with an uncanny talent for looking at an image and immediately sensing what had been changed.

When Mara asked if he could help her compare an original glass plate to a printed version from a local history book, Jonah didn’t ask why.

He only said, “Bring gloves. And don’t drop history.”

They met in the university’s imaging lab, where light was controlled like a ritual. Mara placed the glass plate—borrowed under strict conditions from the Larkhaven archive—on the table.

The image was the same waterworks crew. Jonah scanned it at high resolution, then pulled up the published version from the book, aligned the two, and toggled between them.

At first glance, the difference was subtle. The published version looked cleaner. The contrast was higher. The crop was tighter.

Then Jonah drew a rectangle around the tall worker.

“There,” he said.

Mara leaned in. The published version had been cropped so the top of the arched doorway was cut off. Without the full arch, the scale cues vanished. The tall worker looked merely tall—impressive, but plausible. The doorway looked like a normal door.

Mara’s stomach sank.

“That’s not restoration,” she said. “That’s concealment.”

Jonah’s eyes flicked to her. “Or editorial choice,” he offered, but without conviction.

Mara pulled out another set: a railroad crew photo, the tall figures clustered near a railcar. Published versions existed in a regional magazine.

Jonah scanned, aligned, toggled.

The tall figures were not removed. They were… adjusted. The magazine version had subtle warping around their legs and torso, as if someone had used early digital tools to compress proportions. It wasn’t perfect, but it was good enough for a casual glance.

Mara felt heat rise behind her eyes.

“Someone did this on purpose,” she said.

Jonah nodded slowly. “The question is whether it was one person or many people making the same choice because they think the truth looks embarrassing.”

Mara stared at the screen. The tall worker’s face, in the original, was plainly bored. In the edited version, he seemed slightly hunched, less commanding.

The edit wasn’t just visual. It was psychological.

It took something unsettling and made it manageable.

Jonah pulled up metadata from the magazine’s digital archive. “These edits were done in the early 2000s,” he said. “Not Victorian, not nineteenth-century. Recent.”

“Which means,” Mara said, “someone is still sweeping.”

Jonah glanced at her, then at the door, as if the hallway might be listening.

“Careful,” he said. “If you publish something that implies a coordinated erasure, you’ll attract people who love conspiracies. And people who love lawsuits.”

Mara almost laughed. “I’m a historian. Lawsuits are just alternative peer review.”

Jonah’s mouth twitched, the closest he came to humor.

He saved the comparison files to an encrypted drive and handed it to her like it was a fragile animal.

“Don’t lose it,” he said. “It’s the kind of thing that disappears twice.”

III. The Oversized World

Mara began to walk the Old Quarter with different eyes.

She measured thresholds. She counted stair risers. She photographed handrails that sat a few inches higher than standard. She examined door handles that were set too high for comfortable reach.

Individually, each detail could be explained: an architect’s flourish, a city’s vanity, a style imported from grander places.

Collectively, the details suggested something else.

A world scaled slightly above modern human norms.

Not absurdly above. Not fantasy. Just… enough to make ordinary people feel like guests in a place built for someone else.

In the central library, Mara found a staircase in a restricted wing, blocked by a velvet rope. The stairs led down, not up, into a sealed corridor labeled ARCHIVE—NO PUBLIC ACCESS.

A young staffer named Elise—whose enthusiasm for old paper made her instantly likable—agreed to walk Mara through the inventory list.

“We have maps, ledgers, and some diaries from the Flood Year,” Elise said. “But most personal records got wet. Mud is… not kind.”

Mara waited. “I heard there are sealed rooms.”

Elise hesitated. “There are… structural voids. The building settled when the street level changed.”

“How many?”

Elise gave her a look. “You sound like you want to go in them.”

“I want to know what’s in them,” Mara said, which was technically true.

Elise lowered her voice. “There’s a rumor,” she said. “That the library used to have a lower floor that was filled in. Not collapsed—filled. Like someone decided it shouldn’t exist.”

Mara’s throat tightened. “Who decided?”

Elise shrugged helplessly. “The city, I suppose. Or whoever had shovels and authority.”

That afternoon, Mara requested building permits from the 1890s and early 1900s. She found repeated references to “raising street grade,” “infilling,” “remediating subgrade spaces,” “sealing” and “stabilization.”

All rational. All civic.

But no one wrote: We buried the ground floor because the old one belonged to a different world.

Mara didn’t yet know what she believed about the tall figures. She didn’t have the luxury of certainty. But the architecture didn’t feel like a rumor.

It felt like memory carved into stone.

IV. The Man with the Coal-Stained Hands

The first person to speak openly to Mara about the tall ones—without giggling, without dismissing her, without leaning immediately into sensational mythology—was an eighty-two-year-old man named Lionel Greaves, who lived in a small house behind the old foundry.

Mara met him because she was following a paper trail: a set of foundry employment rolls that included several workers listed with unusually high “uniform measurements.” Not heights—measurements. Shoulder width. Sleeve length. Boot size.

When Mara knocked, Lionel opened the door and examined her with a gaze that was both tired and sharp.

“You the professor?” he asked.

“Yes,” Mara said. “Mara Vance.”

He grunted as if names were optional and stepped aside.

Inside, the house smelled of black tea and coal dust that had seeped into the walls over decades. A small living room held a fireplace, an old armchair, and a shelf of binders stuffed with paper.

Lionel gestured for her to sit, then lowered himself into the armchair with a hiss of joints.

“You’re looking for the long men,” he said, as casually as if he were discussing weather.

Mara’s pen froze over her notebook. “You know about them.”

“I know my grandfather knew them,” Lionel said. “And I know the city prefers people don’t talk about them because it makes tourists nervous in the wrong way.”

Mara swallowed. “What did your grandfather say?”

Lionel reached for a binder, flipped it open, and pulled out a folded letter with careful hands.

“He wrote this in 1903,” Lionel said. “He was a foundry clerk. Not a dreamer. He liked numbers and hated lies.”

Mara took the letter. The handwriting was neat, compressed, and dense, like someone trying to make the page hold more truth than it wanted.

She read silently. The letter described the foundry before the Flood Year. It described shifts where “the tall fellows” worked the overhead rigs with ease, where they adjusted valves and regulators that ordinary men needed ladders to reach. It described how their hands were steady, how they moved with practiced familiarity, as if the machines were extensions of their bodies.

Then the letter changed tone.

It described the months after the mud.

The foundry’s lower level was “gone under.” The regulators were inaccessible. The tall fellows—who should have been valuable, even essential—were absent.

Not dead. Not reported as casualties. Not mentioned in the usual lists of injured or missing. Just… not present.

The clerk wrote:

“It is as if they were never hired, though I signed their papers with my own hand.”

Mara’s fingers tightened around the letter.

“Your grandfather never said where they went?” she asked.

Lionel’s eyes looked far away. “He said men in uniforms came,” Lionel replied. “Not city police. Not army. Something in between. They closed streets. They gave orders. They told people the mud was poison and nobody should go near the old tunnels.”

Mara felt her skin prickle. “Uniforms,” she repeated. “In 1889.”

Lionel nodded. “And he said the tall fellows went with them. Not marching like prisoners. Walking like… like it had been decided already.”

“Decided by who?”

Lionel’s laugh was dry. “That’s your problem, professor.”

Mara stared at the letter again, at the line about papers signed by hand. It was the kind of detail a clerk would anchor to when reality became slippery. A signature. Ink. Proof.

“And you believe him,” Mara said.

“I believe he believed it,” Lionel replied. “And I believe the city buried more than basements. It buried questions.”

Mara lifted her gaze to Lionel. “Why keep the letter?”

Lionel shrugged. “Because someone will come along who can read it without laughing. And because I don’t like being told I didn’t see what my family saw.”

He leaned forward slightly.

“Don’t make it about monsters,” he said. “If you make it about monsters, people will stop listening. Make it about work. About systems. About who got erased when the city decided to rewrite itself.”

Mara nodded slowly. The advice landed like a hand on her shoulder.

Outside, the afternoon light slanted through the window, making dust glitter in the air like tiny, indifferent stars.

V. The Flood Year That Didn’t End

Mara had avoided dramatizing the flood. Disasters invited lazy storytelling: before and after, innocence and ruin, chaos and heroism. But the records refused to behave.

Newspapers from 1889 reported the flood as a catastrophe, then moved on to other headlines within weeks. Yet municipal meeting notes from the following years kept returning to phrases like continuing sediment, recurring deposition, and persistent subgrade instability.

That was odd.

Mud from a flood dried. It was shoveled. It became a memory and a stain. It didn’t keep behaving like a living thing for years.

Mara visited the riverbank on a gray morning when the tide was low. The mud flats spread like a dull mirror. She crouched and dug her fingers into the silt.

It was dense and fine, almost silky. Not the gritty mix of normal flood debris. It clung to her glove like paste. It felt… manufactured.

She heard footsteps behind her and turned. Cal Mercer stood a few paces away, hands in his coat pockets.

“You’re poking the river,” he said.

“I’m poking history,” Mara replied.

Cal came closer and looked out at the flats. “You know what bothers me?” he said. “The city talks about the flood like it was a storm. But if you look at the grade-change projects, it’s like someone used the flood as an excuse to do a massive redesign.”

Mara watched him carefully. “Why would they?”

Cal’s jaw shifted. “Because raising streets solves problems. Pipes freeze less. Sewers flow better. It’s modern. It’s progress.”

“And the cost?”

Cal exhaled. “The cost is you bury whatever was there.”

Mara looked back at the mud. “And if what was there was a network of old chambers and regulators…”

Cal’s eyes narrowed. “Then burying it is easier than explaining it.”

Mara stood and brushed mud from her glove. “Do you think the tunnels connect to the Old Quarter buildings?”

Cal hesitated. “I think there are more voids beneath this city than anyone admits. And I think the city is sitting on a layer of something that doesn’t behave like normal soil.”

Mara’s mind churned. She imagined a city built on systems—water, air, heat, perhaps electricity—systems integrated into architecture like organs. She imagined operators trained to run those systems.

Then she imagined those operators removed.

Not by disease. Not by war.

By decision.

A gull cried overhead. Mara looked up at the sky and felt the absurd, human urge to ask it questions. The gull, mercifully, did not answer.

VI. The Doorway in the Museum

A week later, the museum at East Gate Station hosted a school tour. Mara arrived early, wearing the polite expression of a citizen who was absolutely not planning to trespass.

She waited until a staff member unlocked a side corridor to retrieve supplies. When the door swung open, Mara slipped into the hallway like a ghost with a grant proposal.

The corridor led to a storage room with shelving and cleaning equipment. At the back was a door that didn’t match the rest—older wood reinforced with iron straps, and a frame of stone that looked like it belonged in a cathedral.

It was too tall. Too thick.

It was, in Mara’s mind, a door that remembered different hands pushing it open.

The lock was modern. The hinge pins were old.

Mara didn’t have lockpicks. She wasn’t that kind of academic, despite what her students suspected. Instead, she photographed the doorframe and noticed something carved into the stone at shoulder height.

Not a decorative flourish—a symbol. A small, simple mark like an engineer’s stamp.

She traced it with her finger. The groove was worn, touched by many hands.

Behind her, a voice said, “You’re not supposed to be back here.”

Mara froze. She turned slowly.

A museum staffer stood at the corridor entrance, a young man with a lanyard and a suspicious frown.

“I’m conducting research,” Mara said, lifting her university ID like a shield.

The staffer’s eyes flicked to it, then back to her face. “Research happens with appointments,” he said.

“I tried,” Mara replied. “Your director said no.”

The staffer’s mouth tightened. “Then it’s no.”

Mara took a breath. “I’m not trying to steal anything,” she said. “I’m trying to understand why parts of this building were sealed.”

The staffer’s gaze shifted to the tall door behind her. For a moment, his expression softened into something like fear.

“They say it goes down,” he said quietly.

Mara kept her voice calm. “Who says?”

He swallowed. “Old staff. They said there are rooms that don’t show up on the map. And they said—” He stopped, as if the next words were too ridiculous to be spoken aloud.

Mara waited.

“They said the door was made for people who weren’t us,” he finished.

The phrase hung between them like a damp sheet.

Mara said, gently, “I’ve seen photographs.”

The staffer looked at her sharply. “Then you know why they don’t want you back here.”

Mara held his gaze. “Tell me,” she said.

He looked away. “Because the second you start asking about the tall ones, you attract the wrong crowd,” he said. “People who don’t want answers. People who want to be special for knowing secrets.”

“And the other reason?” Mara asked.

He hesitated. Then, in a low voice: “Because some people think the tall ones weren’t just tall. They think they were… necessary.”

Mara’s heart thumped. “Necessary for what?”

The staffer shook his head, as if refusing the thought itself. “For the building,” he said.

Then he straightened, put the professional mask back on, and said loudly, “You need to leave, ma’am.”

Mara nodded, stepped past him, and walked out with her phone full of images and her mind full of the word necessary.

Outside, children spilled off buses in bright jackets, chattering about pumps and water wheels. Their teachers shepherded them toward the entrance where the ordinary doors welcomed them without complaint.

Mara looked back at the museum’s stone facade. The oversized archway stood above the normal entrance like a mouth closed around a secret.

VII. The People Who Stayed Quiet

Mara didn’t publish immediately. That was the first rule of dangerous research: don’t announce your discoveries until you understand what might happen when you do.

Instead, she interviewed.

She spoke to archivists, engineers, old families. She learned how to ask questions without using the words that made people roll their eyes.

She stopped saying “giants.” She started saying “anomalous heights in early photographs” and “architectural scale mismatches” and “infrastructure discontinuities.” It was less dramatic and more effective.

She found three recurring responses.

-

Polite dismissal: “Interesting, but likely a lens distortion.”

Nervous humor: “Maybe they ate too much porridge back then.”

Careful silence: a pause, a glance, and a change of subject.

The third group was the most revealing.

One woman, a retired nurse, told Mara about hospital logs from the 1880s that listed “unusual patients” with measurements that didn’t fit the standard beds. She said the logs were “misplaced” after renovations.

A former city clerk told Mara that some census pages were missing for specific wards—always the wards closest to the Old Quarter.

A mason who specialized in restoration admitted, over coffee, that he’d seen sealed doorways behind newer brickwork. He said the stone lintels were too high for the visible floors.

“Like a door to nowhere,” he said.

“Or a door to somewhere we don’t use,” Mara replied.

He didn’t smile.

Mara began to see the city itself as a palimpsest—new writing laid over old, not fully hiding what came before. The buildings were polite about it, as buildings often are. They carried the weight of altered ground levels without complaint. They let humans rename their rooms, paint over their symbols, and pretend the proportions were merely aesthetic.

But the doors remembered.

The buried windows remembered.

And in a box in Lionel Greaves’s house, a clerk’s ink remembered signing papers for workers who later became impossible.

VIII. The Chamber

On an evening when fog rolled in from the sea and the city’s streetlamps glowed like distant candles, Mara returned to East Gate Station with Cal Mercer.

Cal hadn’t wanted to come. He’d argued about liability and common sense and how he had a mortgage. Mara had listened, nodded, and then handed him a printout of the embossed plate from the tunnel:

REGULATOR CHAMBER — AUTHORIZED OPERATORS ONLY

Cal had stared at it for a long time, then said, “I hate you.”

“I get that a lot,” Mara replied.

They entered through the staff door again. Cal used his keycard and codes. Mara carried a backpack with headlamps, gloves, a camera, a small laser measurer, and—because she’d watched enough documentaries to respect cliché—two bottles of water and a first-aid kit.

In the basement corridor, Cal opened the hatch.

“Fifteen minutes,” he warned.

Mara climbed down first. The air in the tunnel was colder than the basement, as if the earth itself held its breath.

They walked single file. The corridor walls were stone, fitted with a precision that felt strangely modern. The ceiling arched gently. The floor was flat and worn.

After fifty yards, they reached a metal door set into the stone. It was enormous.

Not a city maintenance door. Not a modern security door. An old door—thick, riveted, and framed by a stone arch that echoed the ones above ground.

Cal shined his light around the edges. “No hinges,” he murmured. “Sliding?”

Mara traced the grooves in the floor. “Like it was meant to be moved easily,” she said. “By someone strong.”

Cal looked at her. “Or by a mechanism.”

They found a wheel set into the wall—an iron handwheel with spokes thick as Mara’s wrist. It sat too high for comfortable reach. Cal had to stretch to grasp it.

Mara didn’t tell him she’d noticed. She just watched.

Cal turned the wheel. It resisted, then moved with a groan that echoed down the corridor like a waking animal. Somewhere inside the stone, gears answered.

The metal door shuddered, then slid sideways with slow, reluctant grace.

A chamber opened before them.

Mara’s light swept across a vast room, circular, with walls lined by metal conduits that rose and vanished into the ceiling. The ceiling itself was high—higher than any basement had a right to be. In the center stood a structure like a pedestal, ringed with brass fittings and glass cylinders. The glass was dark with age.

The chamber felt less like a storage space and more like a heart.

Cal stepped in, breathing shallowly. “This isn’t on any map,” he whispered.

Mara moved closer to the central pedestal. On its surface were engraved markings—not ornate, not decorative. Functional. Labels.

INPUT

FLOW

HARMONIC

GROUND

Cal followed her gaze. “Harmonic,” he repeated. “Like sound?”

Mara didn’t answer immediately. Her mind ran through possibilities like a hand flipping index cards.

Energy systems. Pressure systems. Resonance. Regulation.

A building that wasn’t just shelter.

A building that did something.

She circled the pedestal and found a series of levers mounted higher than her head. The levers were worn smooth at the grip points. They had been used, repeatedly, by hands that reached them easily.

Mara swallowed.

Cal’s voice trembled, angry and awed at once. “Who built this?” he demanded softly, as if he expected the chamber to reply.

Mara pointed her light upward. Along the walls were platforms—catwalks, perhaps—set at a height that seemed designed for someone to step onto without climbing ladders.

There were no ladders.

Cal saw it too. His face went pale.

“They didn’t need ladders,” he said.

The words landed with the weight of inevitability.

Mara’s chest tightened. The chamber didn’t prove “giants” as myth portrayed them. It didn’t confirm a secret empire or a fantastical origin story. But it did something more dangerous to a careful mind:

It made a different past feel not only possible, but practical.

Operators. Not legends.

Workers. Not monsters.

People whose bodies fit this space the way Mara’s fit a modern doorway.

Cal backed away. “We should go,” he said.

Mara nodded reluctantly. She photographed everything she could in a few frantic minutes. Then she saw it: a plaque on the wall, half-covered by mineral deposits.

She scraped gently with her glove, revealing an emblem—simple, stamped, official.

Beneath it, a single sentence:

MAINTENANCE TRANSFERRED — 1891

Cal stared. “Transferred to who?”

Mara didn’t speak. Her mind supplied answers she didn’t yet have the courage to say.

When they reached the hatch again, Cal slammed it shut with more force than necessary, as if sealing the chamber could seal the implications.

They stood in the basement corridor, breathing hard.

Cal looked at Mara. “If this gets out,” he said, “the city will go nuclear.”

Mara’s voice was steady, but her hands shook. “Then it already matters.”

IX. The Story That Fights Back

Mara spent the next month writing a paper that tried to do the impossible: describe the evidence without turning it into a circus.

She focused on:

documented changes in street grade and building infill after the Flood Year

sealed substructures not present in modern schematics

photographic anomalies and subsequent editorial “normalization”

employment rolls with nonstandard measurement notes

the existence of a functional-looking regulator chamber with dated maintenance transfer

She avoided claiming a hidden empire. She avoided grand conclusions about global coordination. She did not use the word “Tartaria,” not because she feared it, but because she refused to let her work be swallowed by a prepackaged narrative.

She wrote instead:

“The built environment suggests adaptation to lost infrastructure and potentially lost operational knowledge. The absence of certain bodies from later documentation may reflect social, institutional, or editorial processes rather than biological disappearance alone.”

It was cautious. It was academic.

It was also, she realized, not enough.

Because the moment she submitted her draft to a journal, her inbox changed. Messages arrived from strangers with subject lines like YOU’RE CLOSE and STOP DIGGING and MY GRANDMOTHER KNEW THEM.

One message was a single sentence:

“The doorways were not oversized. You got smaller.”

Mara stared at it for a long time, her mouth dry.

She imagined a historian’s nightmare: not that the past was unknown, but that it was known and deliberately withheld.

She imagined a catastrophe that could be used as cover—not necessarily engineered, but exploited. In chaos, people accept new stories. They accept omissions. They accept silence because silence feels safer than uncertainty.

She thought of children at the museum, pressing buttons to make miniature pumps run.

She thought of levers in a buried chamber that no one touched anymore.

And she thought of the tall worker in the 1878 photograph, bored in the way only someone doing normal work can be bored.

Not posing for myth. Just standing there, existing, before someone decided that existence was inconvenient.

X. What the Doors Ask of Us

On the morning Mara presented her findings at a small symposium—carefully framed, evidence-forward, no sensational claims—she watched faces in the audience.

Some looked intrigued. Some looked amused. Some looked angry, as if her questions were an accusation.

Afterward, an elderly woman approached her with slow certainty. She wore a coat too warm for the season, and her eyes were clear.

“My father was a carpenter,” the woman said. “He taught me something. He said you can tell who a building was made for by what it forgives.”

Mara blinked. “What it forgives?”

The woman nodded. “A good house forgives a child running too fast. A good staircase forgives an old knee. A good doorway forgives a man carrying furniture.”

She leaned closer.

“Those old buildings,” she whispered, “don’t forgive us. We bump into their handles. We crane our necks under their arches. We make their lower windows into basements because we don’t want to admit they used to be rooms.”

Mara’s throat tightened. “Why would anyone hide that?”

The woman’s mouth thinned. “Because it suggests we inherited something we didn’t build,” she said. “And people who claim power don’t like admitting inheritance. They like claiming authorship.”

Then the woman patted Mara’s arm and walked away, leaving Mara with that word—forgives—ringing in her mind like a bell.

That evening, Mara returned alone to the Old Quarter courthouse. The street was empty. The stone facade loomed, solemn and patient.

She stood before the monumental entrance and looked up at the archway. She imagined it in 1878, in 1889, in 1891. She imagined footsteps passing through that were longer-strided, shoulders higher, hands larger. She imagined their laughter, their fatigue, their ordinary arguments about pay and weather and the taste of tea.

And she imagined the moment they were told to go.

Not as prisoners, perhaps. Not with chains. Maybe with paperwork. Maybe with promises. Maybe with threats that didn’t need to be spoken aloud because power has a way of making obedience feel like the only sensible option.

Mara put her palm against the stone. It was cold, even in summer. The city’s hum was distant.

She realized something that made her feel both smaller and steadier:

The mystery wasn’t just about where they went.

It was about what a society chooses to remember.

If tall workers could be edited into normal proportions, if rooms could be filled and renamed, if entire layers of a city could be buried and then called “basements” with a straight face—then history was not only a record.

History was a negotiation.

And sometimes, a theft.

Mara stepped back and looked once more at the oversized doors.

They did not open for her. They did not need to. They had already done their work.

They had reminded her that the past is not a finished story. It’s a structure we walk through every day—often without noticing the parts that don’t fit us.

And once you notice a doorway that doesn’t fit, you start wondering who it was built for.

And what it cost to make us forget.

News

He Took a Baby DOGMAN Home. His Family Thought It Was Normal, Until One Day…

He Took a Baby DOGMAN Home. His Family Thought It Was Normal, Until One Day… The Pup That Spoke Three…

I Found My Missing Wife Living With a Bigfoot in a Remote Cave – What She Told Me Changed Everything

I Found My Missing Wife Living With a Bigfoot in a Remote Cave – What She Told Me Changed Everything…

My Parents Hid Twin DOGMEN for 20 Years, Then Everything Went Terrifyingly Wrong…

My Parents Hid Twin DOGMEN for 20 Years, Then Everything Went Terrifyingly Wrong… The Children of the Timberline Twenty Years…

Man Saved 2 Small Bigfoots from Rushing River, Then He Realized Why They Were Fleeing – Story

Man Saved 2 Small Bigfoots from Rushing River, Then He Realized Why They Were Fleeing – Story RIVER OF BONES,…

A Farmer’s War Dog Fought 3 Werewolves to Protect His Family — But He Didn’t Survive

A Farmer’s War Dog Fought 3 Werewolves to Protect His Family — But He Didn’t Survive Gunner’s Last Stand The…

Police Discovered a VILE Creature Caught on Camera — What Happened Next Shocked Everyone!

Police Discovered a VILE Creature Caught on Camera — What Happened Next Shocked Everyone! THE QUIET CARTOGRAPHY OF MONSTERS The…

End of content

No more pages to load