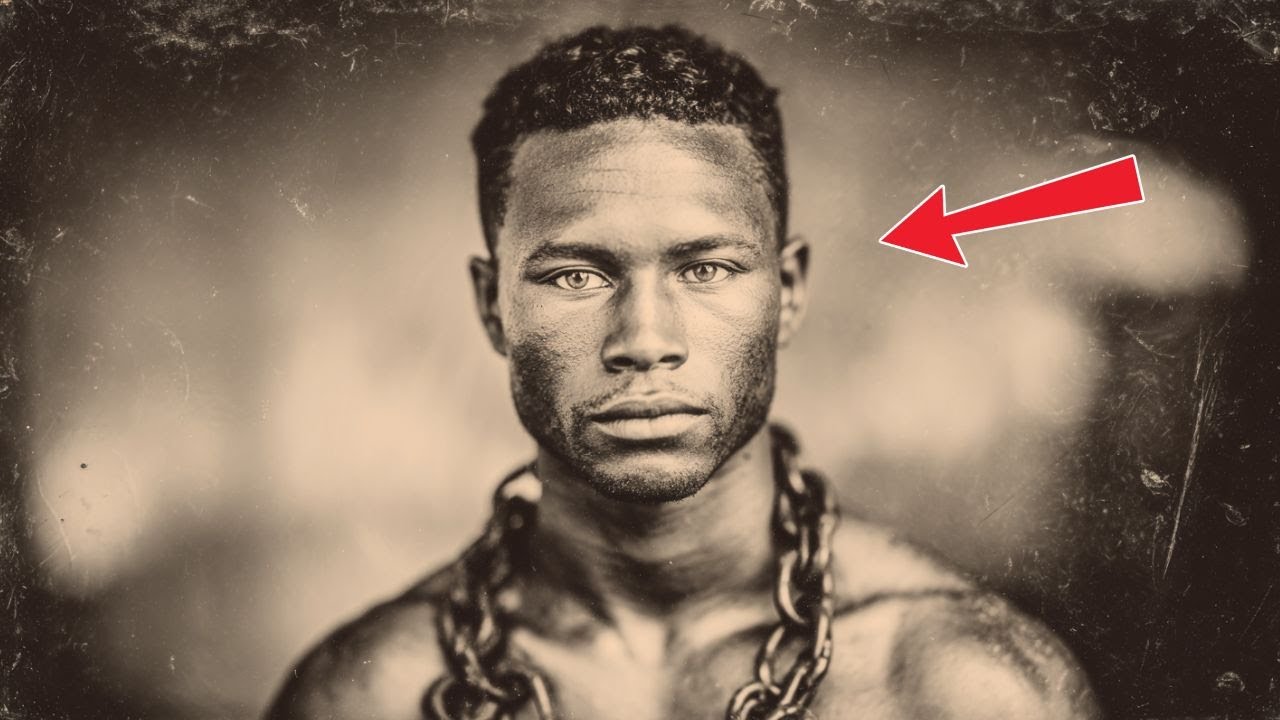

The Most Beautiful Slave Ever Sold in New Orleans — The Man No One Could Bear to Look At, 1851

In 1851, on a humid November morning in New Orleans, the slave auction house on St. Louis Street filled long before the bell.

Plantation owners came in their best coats, wiping sweat from their necks. Slave traders leaned under the gallery rail, joking too loudly. Street vendors pressed pralines and meat pies into hands. Even people with no intention of buying pushed inside and up against the walls.

They weren’t there for sugar hands or house girls.

They were there to see him.

Rumors about Aurelius had been running up and down the Mississippi for weeks: that he was the most beautiful man ever brought to market; that he spoke French, English, Latin, and two African tongues; that no one could look him in the eye and feel unchanged.

They said his last owner’s wife had taught him to read in secret. They said her husband had found out and died in a fire that never touched the rest of the house.

They said a lot of things. In New Orleans, people always did.

Madame Celestine Beaumont, sixty‑three and dressed in black silk despite the heat, had heard it all. Her carriage rolled up to the auction house just after ten. She usually sent her agent to bid for her. Today she had come herself.

Her plantation, Belle Rive, lay upriver: three thousand acres of cane and 147 enslaved people whose names were written in ledgers beside their appraised value. She had inherited the land and most of the people from her husband. Over the years she had added more—quietly, efficiently, the way one added mules or machinery.

She told herself she was kinder than most. She fed people. She rarely whipped. She attended church and wrote checks to charities.

She slept well.

Most nights.

But as she watched the crowd push into the auction house, she felt a tightness under her ribs she could not explain. Her maid, Josephine, had said, “He looks at you, madame, and you understand, for the first time, what it costs you to own someone. Cousin says the others in the pens won’t even stand near him.”

Celestine had laughed it off, then dressed in her finest green day dress.

Now, inside the packed exchange, she wondered why her hands were damp.

The auctioneer, coat clinging to his back, began with the usual: crates and barrels, old furniture, a mother with a baby at her breast, two boys from Virginia with strong shoulders and downcast eyes. Men prodded arms and opened mouths; women hid their distaste behind lace gloves.

Celestine watched without really seeing. Her gaze kept sliding toward the heavy curtain at the back of the platform.

So did everyone else’s.

After an hour, the auctioneer set down his ledger and wiped his brow.

“Ladies and gentlemen,” he called, and his practiced bark sounded oddly strained. “We come now to Lot 47. A specimen without equal in this market or any other. Educated. Sound of body. Exceptional in every regard. We begin at five thousand dollars.”

Even men who’d come only to watch sucked in a breath. Five thousand could buy a dozen strong field hands. It could pay off debts that kept a plantation afloat.

The auctioneer nodded to his assistant.

The curtain drew back.

Aurelius stepped into view.

For a heartbeat, no one reacted. Then the room itself seemed to inhale.

He was tall—taller than most white men present—with skin the color of polished copper, catching the light in warm planes along cheekbone and jaw. His shirt and trousers were the coarse white cotton given to any person about to be sold, but on him they looked like something else entirely, like robes you’d see on a saint in a French painting.

His features were so precisely balanced that Celestine’s mind, searching for a flaw, found none. Full mouth, straight nose, high cheekbones, the faint shadow of a dimple when his lips parted in something that wasn’t quite a smile.

But later, no one remembered those details first.

They remembered his eyes.

They were very dark, almost black, but with flecks that caught the lamplight—bits of amber, gold, something unnameable. When he let his gaze drift across the crowd, people flinched as if struck.

It wasn’t that he glared.

It was that he saw.

One by one, his eyes met theirs: the judge who’d sentenced runaways to hangings; the merchant whose warehouse quietly doubled as a holding pen; the planter who had bragged over brandy about working men to death and buying more.

When Aurelius looked at them, something inside them tilted.

Celestine felt it when his gaze reached her.

For just a second, everything she was—wealthy widow, devout Episcopalian, “kind” mistress—fell away like painted scenery. In its place she saw herself as if from a great height and terrible proximity at once.

She saw the sugar flowing north on steamboats. She saw the hands that cut it, the backs that bent, the children born into a life where their first cry belonged to someone else’s ledger. She saw herself signing bills of sale, selecting bodies like fabrics, telling herself she was humane because she allowed music on Sundays.

She heard again her husband’s last words, whispered in fever twelve years earlier: When you stand before God, Celestine, what will you say?

She had never told anyone he’d asked her that. She had tucked the memory away like a letter in the wrong drawer.

Under Aurelius’s gaze, the drawer flew open.

Her eyes burned. She blinked hard, furious with herself, but tears spilled anyway, streaking her powder.

Nearby, Philippe Deveaux—her neighbor upriver, a man whose cruelty to his enslaved people was an open secret and a private horror—made a sound like an animal and turned his face to the wall.

Judge Leblanc, who had never visibly doubted a sentence in thirty years, gripped his cane so hard his knuckles blanched. His lips moved soundlessly.

The auctioneer tried to recover his rhythm.

“As you can see,” he said, voice hitching, “this is truly a remarkable specimen. Educated. Literate. Suitable for house service, personal attendance, or…or special duties. We begin at five thousand. Do I hear five?”

Silence.

A fly buzzed near the lamps. Somewhere at the back, a child whimpered and was hushed.

“Four thousand, then,” the auctioneer said. “Four?”

No hands went up.

Men who had planned to see and be seen suddenly found the scuffed floorboards very interesting. One wiped his face with his handkerchief again and again as though trying to remove something invisible.

“Three thousand.”

Nothing.

Celestine tried to lift her hand. Her arm would not move. It was as if some thread between her intent and her muscles had been cut.

“Two thousand, then. Gentlemen, this is absurd. Two thousand?”

Philippe licked dry lips. “One thousand,” he rasped. “I’ll give you one. Take it and be damned.”

Relief flashed across the auctioneer’s face. “One thousand. Thank you, Monsieur Deveaux. Do I hear fifteen hundred?”

Before he could coax another number, Aurelius turned his head fully and *looked* at Deveaux.

It wasn’t a glare. It wasn’t pleading.

It was simply a steady, focused attention, as if Aurelius were looking not at the man’s shape and clothes but straight through to something under his ribs.

Philippe staggered.

A sound caught in his throat. His hand flew to his chest. For a wild second Celestine thought he might collapse.

Then he spun around and shoved his way toward the door, knocking into shoulders and hats, gasping under his breath, “No. No. No—”

The room broke.

A woman in the second row began sobbing openly. A man near the wall swore and pushed for the exit. A planter from St. Bernard Parish, who had never been uneasy in his life, lurched to his feet as if to run and then froze halfway, panting.

“Sit. Sit down!” the auctioneer shouted, panic edging his voice. “We’ll have order or I’ll—”

No one listened.

It was as if Aurelius’s gaze had tilted the floor and everyone had to grab for whatever opening they could find to keep from falling into something inside themselves.

People clawed toward the doors. Some bowed their heads and clutched their rosaries. Others muttered prayers. A few simply stood, rooted like Celestine, and stared back as if trying to see whether there might be mercy in those eyes.

There was no anger in Aurelius’s face.

There was sadness, yes. And something like pity.

It made it worse.

At last Josephine’s hand closed around Celestine’s arm.

“Madame,” she whispered. “We must go.”

Celestine tore her gaze away and let herself be led out into the blistering light of the street, where the crush of ordinary life—peddlers, carts, the smell of coffee and sewage—felt suddenly unreal.

By dusk, the story was everywhere.

They said a slave so beautiful no one could look at him had stood on the block and broken an auction with his eyes alone.

They said the chains on his feet had popped open without being touched.

They said a dozen white men, hardened by profit and habit, had wept like children and fled.

And the next morning, when the auctioneer went back to check on the “specimen” no one had been able to bid for, Aurelius was gone.

The iron cuffs lay on the plank floor, still locked, their pins unbroken.

The cell door was barred from the outside. The single window was too narrow for a child, let alone a grown man.

He had not climbed, or dug, or cut.

He simply was not there.

A reward notice went up within hours: TWO THOUSAND DOLLARS for the capture of one Aurelius, Negro male, six foot two, approximately twenty‑five years of age, possessing a scar under the left shoulder blade (the only imperfection they could think to mention).

Slave catchers loosed their dogs. The city watch searched attics and waterfront shacks. Riders scoured cane fields and cypress breaks.

They found tracks that led to water and disappeared. They found people who swore they’d given directions to a tall, polite man who spoke better French than they did.

They did not find him.

Instead, something stranger began.

Men who had been in the auction house started seeing eyes in places where no eyes should be.

Looking into their shaving glass, they caught—not their own gaze exactly, but that same dark, knowing look, as if someone behind the mirror were watching. Bending to rinse their hands in the river, they saw a face in the water’s shifting surface, not solid but unmistakable.

He looked at me, they would say afterward in low, shaken voices. And he knew.

He knew about the girl I sold away from her baby. He knew about the man I watched die in the swamp because it was cheaper than pulling him out. He knew about the time I laughed when a boy screamed.

He knew everything I’ve never admitted. Not even to myself.

Not everyone who’d been there saw him.

Some did what human beings usually do when truth pricks too close: they buried it under work, drink, brutality. They whipped harder, boasted louder, invested deeper, as if doubling down on cruelty could drown out whatever had shaken loose.

Others, like Celestine, found they could not.

In the weeks after the auction, she sat for long hours in her study, ledger open, ink drying in her pen. Sometimes she picked up her quill. Sometimes she merely stared at the names written in neat columns: Abraham, age 67. Josephine, age 52. Caleb, age 19. Next to each, a number: $600, $800, $1,200.

She had never thought before about how it felt to be reduced to that.

She asked Josephine, one evening, what she would do if she were free.

Josephine answered, after a long time, “I would look for my daughter. The one they sold from my arms when she was eight. That was thirty‑two years ago. I don’t know if she is alive. But I would look until I found her. Or I died.”

Celestine had not known Josephine had a daughter.

She had never asked.

Sorrows she had floated on like a ship on a dark sea were suddenly visible underneath, vast and jagged.

She couldn’t sleep.

She started making small changes at Belle Rive. Shorter hours. Better food. No more selling families apart. The overseer grumbled. Neighbors muttered. None of it touched the core problem and she knew it. A velvet collar is still a collar.

One foggy morning three months later, walking alone in her garden, she saw him at the far gate.

He didn’t look like a fugitive.

He stood easy, hands at his sides, clothes plain. The mist made him half unreal. But his eyes were the same.

“Are you real?” she asked, absurdly, because what else was there to say?

“What is real?” he answered. His voice was low, with a cadence that made every word feel chosen. “Your papers? Your deeds? The law that says one soul can own another? Those things seem real because everyone agrees to pretend they are. But they crumble. You have seen it.”

“I’ve tried to do better,” she said. “To…soften things. To prepare them for—if the law changes…”

“You cannot make an unjust thing gentle,” Aurelius said. “You can only end it.”

“I free them all,” she snapped, more at herself than at him, “and in thirty days the law says they must leave the state or be seized again. If I let them go at once, with no money, no papers, they’ll be hunted down by men with dogs. If I petition to free them one by one, the courts will block me. I am old, but not so foolish as to think good intentions alone will save anyone.”

“There are roads north,” he said. “Rivers. Friends you have not met yet. You have money. Sway. You can use them for what they were not meant for. The question is not whether paths exist, Madame Beaumont.

“It is whether you will take them.”

“And if I do?” she asked hoarsely. “If I ruin myself, lose my friends, my land, my name—will that be enough?”

“It will not balance what has been done,” he said. “Nothing can. But it will be a beginning. The only kind there is.”

His voice thinned, like sound through fog. “You asked me once, in your heart, what you would say when you stood before God. You need not fear that day if you begin telling the truth now.”

She reached for him.

Her fingers closed on empty air.

The mist by the gate folded in on itself and drifted away.

An hour later she stood on the upstairs gallery of Belle Rive and faced everyone the law said belonged to her. One hundred and forty‑seven faces turned up, wary, hoping, skeptical.

“I have done you great wrong,” she said. “Every day of your lives, I have profited from your bondage. I told myself I was better than others. That lie died the day I saw a man named Aurelius.”

She told them, in plain words, what she intended: shorter hours, wages paid into their own hands, no more sales, and—over months and years—manumission papers, passage north, new lives.

The law would fight her, she warned them. Her peers already hated her for even thinking of it. This would be dangerous for all of them.

But she would not turn back.

An old man at the front, Abraham, lifted his head. “Why now, Miss Celestine?” he asked. “What changed you after all these years?”

She thought of Aurelius on the block, of his eyes like dark water and reflected fire.

“I looked into a mirror,” she said. “And I believed what I saw.”

Word spread faster than cane fire in a dry field.

Social invitations ceased. Old friends crossed the street rather than greet her. Men who had tipped their hats began spitting her name like a curse. The bishop wrote to inform her she had lost the church’s blessing.

She sold land and silver to buy train tickets, river passage, boots, blankets. A Quaker in Ohio wrote back with names of people who would meet small parties of ex‑slaves at the depot and help them into Canada. A free Black pastor in Philadelphia promised jobs for men who could work and a school for their children.

Every few weeks another wagon left Belle Rive in the dark: families with parcels and new surnames, their faces packed with fear and wild, fragile hope. Some made it north. Some didn’t. Dogs and deputies and bounty men went out after them. Celestine could not control everything.

But the ledgers in her study began to empty of numbers and fill with notes: ABRAHAM FREEMAN—CINCINNATI. JOSEPHINE BELL—BOSTON. CALEB JONES—UNKNOWN.

When the sheriff came with his warrant—AIDING FUGITIVE SLAVES, INCITING REBELLION, CONSPIRACY—Josephine begged her to flee with the next wagon.

“If I run now,” Celestine said, smoothing her dress, “they will say I acted only from madness and panic. If I stay and speak, perhaps someone will hear. I have hid my face for sixty years, Jo. I am tired of it.”

They put her on trial before men who had all, in their time, stared down from the steps of that same auction house and called bids on human flesh.

She didn’t deny a charge.

“I broke your law,” she told the jury. “I would break it again. There are times when obedience is just another word for cowardice.”

She spoke of Aurelius and the day the auction stopped. The prosecutor tried to paint it as hysteria. The judge ordered the remarks stricken. The newspapers printed them anyway.

They sentenced her to fifteen years at hard labor.

She lasted three.

In the damp stone of the women’s prison, pneumonia finished what the courts had begun. Josephine buried her with her own hands in a small plot behind a Black church and paid for a wooden marker out of the wages Celestine had insisted on giving her.

Up north, men and women who had once bent their backs in her fields gathered around kitchen tables and in church basements when the news reached them and bowed their heads in something that was not quite mourning and not quite forgiveness.

They told their children: She was wrong a long time. Then she tried to be right, even when it killed her. Remember that.

As for Aurelius, he was never captured.

But stories kept walking the river roads.

A Union chaplain wrote in his diary about a tall Black man who moved calmly among the wounded at Shiloh, whispering to men on both sides and pressing their hands until they stopped shaking.

A woman in Philadelphia claimed that, when she could not decide whether to open her cellar to two runaway boys, she looked up and saw a familiar face reflected in the glass of her lamp, watching, waiting. She opened the door.

In New Orleans, decades after emancipation, old folks still leaned on porch rails at dusk and told the young ones, “I was there, you know. I saw him on the block. I couldn’t bear it. I ran. But he saw me.”

The children would laugh or shiver, depending on their temperaments. Then, later, washing their faces in a basin under a cracked mirror, one or two might linger on their own reflection, suddenly aware of a question rising in them like a tide:

If someone looked at me and knew everything—everything—I have done and failed to do, what would I see in their eyes?

That was the legacy of the man they called the most beautiful slave ever sold and never sold at all: not a neat miracle, not a folklore ghost to frighten children, but a terrible, liberating gift.

He made people see themselves.

What they did with that sight was never his to control.

It is never anyone’s.

That part has always been, and still is, ours.

News

Michigan Bootlegger Vanished in 1924 — 100 Years Later, His Secret Tunnel System Found Under Woods

Michigan Bootlegger Vanished in 1924 — 100 Years Later, His Secret Tunnel System Found Under Woods The mist hung low…

The Hazelridge Sisters Were Found in 1981 — What They Said Was Too Disturbing to Release

The Hazelridge Sisters Were Found in 1981 — What They Said Was Too Disturbing to Release In January 1981, the…

Plantation Daughter Ran North With Father’s Slave in 1853… What They Found 6 Months Later

Plantation Daughter Ran North With Father’s Slave in 1853… What They Found 6 Months Later On a cold, moonless night…

Navy SEAL Exposes the Truth About Narco-Terrorist Strikes: Why Politicians Don’t Understand War

Navy SEAL Exposes the Truth About Narco-Terrorist Strikes: Why Politicians Don’t Understand War A former Navy SEAL is speaking out…

LIVE: Caitlin Clark SHOCKS Fans — CANCELS Europe Deal to Join Team USA!

LIVE: Caitlin Clark SHOCKS Fans — CANCELS Europe Deal to Join Team USA! In a stunning move that has sent…

The Grayson Children Were Found in 1987 — What They Told Officials Changed Everything

The Grayson Children Were Found in 1987 — What They Told Officials Changed Everything There’s a photograph in the county…

End of content

No more pages to load