# The Stitched Mask: A Forgotten Experiment in the House of Little Shadows

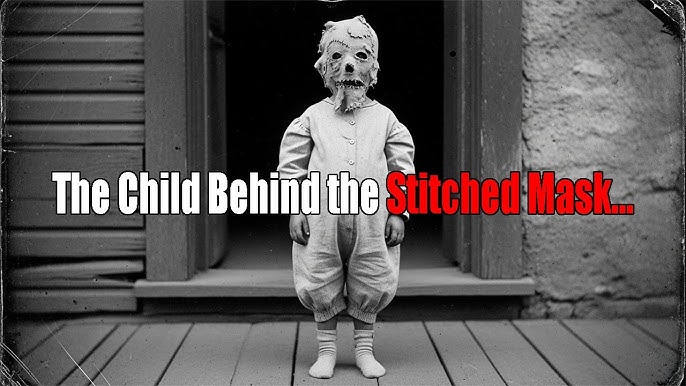

In 1987, during the demolition of an old orphanage in rural Pennsylvania, a chilling photograph was discovered among the rubble. It was preserved between two glass plates, as if someone had desperately tried to protect it or hide it from the outside world. This single image, known as The Stitched Mask, would later be linked to one of the most disturbing medical experiments of the early 20th century, revealing a dark history that had long been buried.

The photograph depicts a small girl, likely between six and eight years old, dressed in a white outfit that resembles a shroud more than ordinary clothing. Her face is obscured by a grotesque mask, stitched directly into her skin with irregular, coarse thread. To understand the horror captured in this photograph, we must journey back to the year 1914.

America was on the brink of entering World War I, but within its borders, another battle was being fought—one against diseases that claimed lives at an alarming rate. The summer of 1914 was particularly brutal, marked by a smallpox epidemic that swept through several rural communities in the northeastern states. This was not the smallpox we recognize today; it was a virulent strain that left deep, disfiguring scars, particularly on children. Medical records from Harrisburg General Hospital detailed cases where the pustules were so severe that facial tissue detached, leaving permanent craters that transformed children’s faces into grotesque masks of scarred flesh.

In this context of medical desperation, a disturbing practice emerged. Poor families, unable to afford proper medical treatment or reconstructive surgeries, began creating their own solutions. Cloth masks sewn at home became commonplace in certain communities. However, there was something darker happening—something that official records seem to have deliberately omitted or destroyed.

Dr. Samuel Hartley, a rural physician, kept a detailed diary of his observations. In September 1914, he wrote, “Today I saw something that will disturb my sleep for the rest of my days. A child was brought to me, not for treatment, but so that I could attest that it was still alive. The face was covered by a linen mask sewn with such brutality that I wondered if the stitches didn’t pierce the skin itself. When I asked to remove it, the mother screamed as if I had suggested tearing out the child’s soul. She muttered something about keeping the spirits inside before fleeing with the child in her arms.”

Hartley’s account was not unique. Scattered through medical archives and personal diaries of the time are fragmentary references to children with covered faces, always accompanied by an uncomfortable silence about what was being hidden. Was it merely physical deformity, or was there something more sinister at play?

The photograph in question presents details that defy simple explanations. When examined with modern digital techniques, the child’s white outfit reveals patterns of stains identified as consistent with bodily fluids, but not blood. Forensic experts could not determine the source of these stains, which did not correspond to any known biological substance.

Even more disturbing is the child’s posture. The photograph captures her in a perfectly rigid position, a remarkable feat considering that wet collodion photographic exposures of the era required subjects to remain absolutely still for up to 15 seconds. Any parent knows how impossible it is to keep a child still for that long, unless the child was somehow restrained or incapacitated.

The orphanage where the photograph was found had a peculiar history. Founded in 1903 by a group of anonymous benefactors, it was known locally as the House of Little Shadows—a name whispered with a mixture of pity and fear. Official records are scarce, but a few mention a special wing separated from the main building where certain children were kept for their own welfare and the welfare of others. A 1915 state inspection report noted, “Conditions are adequate, although we cannot help but note the excessive use of physical restraints and facial coverings.”

1914 was also the year of a rare astronomical phenomenon—a total solar eclipse that passed directly over the region on August 21st. Ancient cultures believed that during eclipses, the veil between the world of the living and the dead became thinner. Curiously, records indicate a spike in unexplained incidents in medical institutions and orphanages during the weeks following the eclipse.

The chemical composition of the wet collodion used in this photograph adds another layer of mystery. Modern analyses detected traces of substances not typically present in the photographic process of the time, including mercury and arsenic. Both were used in questionable medical treatments of the era, particularly those intended to calm disturbed spirits in children considered possessed or mentally unstable.

The mask itself is particularly noteworthy. The pattern of stitches is not random; when mapped, it resembles symbols found in medieval grimoires associated with containment or imprisonment. This raises the possibility that the mask served a purpose beyond mere aesthetics.

Moreover, the absence of a photographer’s credit on the image is unusual for professional portraits of the era. Photographers typically marked their work with pride, especially when using the complex wet collodion technique. The lack of identification suggests the photographer may not have wanted to be associated with this particular image, or perhaps couldn’t be identified for reasons best left unexamined.

A detail that went unnoticed until recently is the reflection visible in the eyes through the mask’s holes. Extreme digital magnification revealed silhouettes of several figures standing around the child, outside the photo’s frame. However, the wet collodion process of the era lacked the resolution to capture such details. Yet there they are—spectral figures that shouldn’t exist, captured in an image that shouldn’t be able to capture them.

Investigations into the orphanage revealed it was abruptly closed in 1919, just five years after the photograph was taken. Official reasons cited financial difficulties, but letters from staff members paint a different picture. A housekeeper wrote, “The children from the special wing were finally taken away. No one said where, and we were instructed to never speak about them again. They burned all their things except… well, it’s better not to say. Some things are better forgotten.”

What happened to these children? Official records are silent. Death certificates, transfer records, adoption documents—nothing. It’s as if they simply ceased to exist. The only evidence of their existence is this solitary photograph and the fragmentary whispers in forgotten documents.

In 2003, an amateur genealogist researching American orphanages made a disturbing discovery. He found census records showing a spike in the child population of several small Pennsylvania towns in 1920, exactly one year after the orphanage closed. These children appeared in the records with no birth history or identifiable parents, living with families that claimed informal adoptions but could provide no documentation.

Even stranger, physical descriptions of these children in school records frequently mentioned unusual facial features or disfiguring birthmarks that required them to wear facial protection for medical reasons. A teacher at a rural school wrote in her diary in 1922, “The little one from the Morrison family always wears that horrible mask. They say it’s because of burns, but I swear sometimes I see the mask move in ways that cloth shouldn’t move, as if there was something underneath trying to get out.”

The wet collodion technique itself adds another sinister dimension to this story. The process required that the glass plate be sensitized, exposed, and developed while still wet, all within about 15 minutes. This meant that the photographer had to have a mobile laboratory nearby or work under very specific conditions. The chemicals used created toxic fumes that could cause hallucinations and neurological damage. Many photographers reported seeing things that weren’t there during long work sessions.

The photograph we see today represents more than just a disturbing portrait of a masked child. It offers a glimpse into a period of American history where the boundaries between medicine and superstition, science and occultism, life and death, were much more porous than history books suggest. Perhaps the mask wasn’t meant to hide deformity, but to contain something. Perhaps the crude stitches were the result of urgent desperation.

The orphanage was demolished in 1987, but the land remains empty. Attempts to construct on the site were abandoned after workers reported unspecified technical difficulties. Local residents avoid the area, especially in October when they claim to hear the sound of children singing songs in a language no one understands.

The original photograph now resides with a private collector who wishes to remain anonymous. He keeps it in a temperature-controlled safe, not for its historical value, but because he believes it needs to be contained. When pressed about what he meant, he simply shook his head and muttered something about doors that shouldn’t be opened.

In the end, the story of The Stitched Mask remains shrouded in mystery. It is a haunting reminder of the past, a glimpse into a world where the line between life and death was blurred, and where the secrets of the House of Little Shadows continue to linger in the shadows, waiting to be uncovered.

News

It was just a photo of two friends — but it holds a secret that no one had noticed — until now

# The Haunting Photograph of William and James In 1906, a seemingly ordinary photograph captured a moment that would haunt…

In the 1906 photo, the group smiles before the house—but a figure waves from behind the glass

# The Haunting Photograph of the Hawthorne House In 1906, a seemingly ordinary photograph captured a moment that would haunt…

# The Haunting Photograph of Evelyn Gray: A Dark American Folklore

# The Haunting Photograph of Evelyn Gray: A Dark American Folklore In 1910, a photograph captured a moment that would…

# The Bride Who Heard Voices of Her Ancestors — A True Dark American Folklore

# The Bride Who Heard Voices of Her Ancestors — A True Dark American Folklore In the heart of Kentucky,…

# She Was Pregnant by Her Own Son — The Darkest Secret Hidden in the Mountains

# She Was Pregnant by Her Own Son — The Darkest Secret Hidden in the Mountains Deep in the mountains…

The Whitlock Photograph — The Family Dinner That Ended in Poison (1873)

# The Whitlock Photograph: The Family Dinner That Ended in Poison In 1873, a seemingly innocuous photograph captured a family…

End of content

No more pages to load