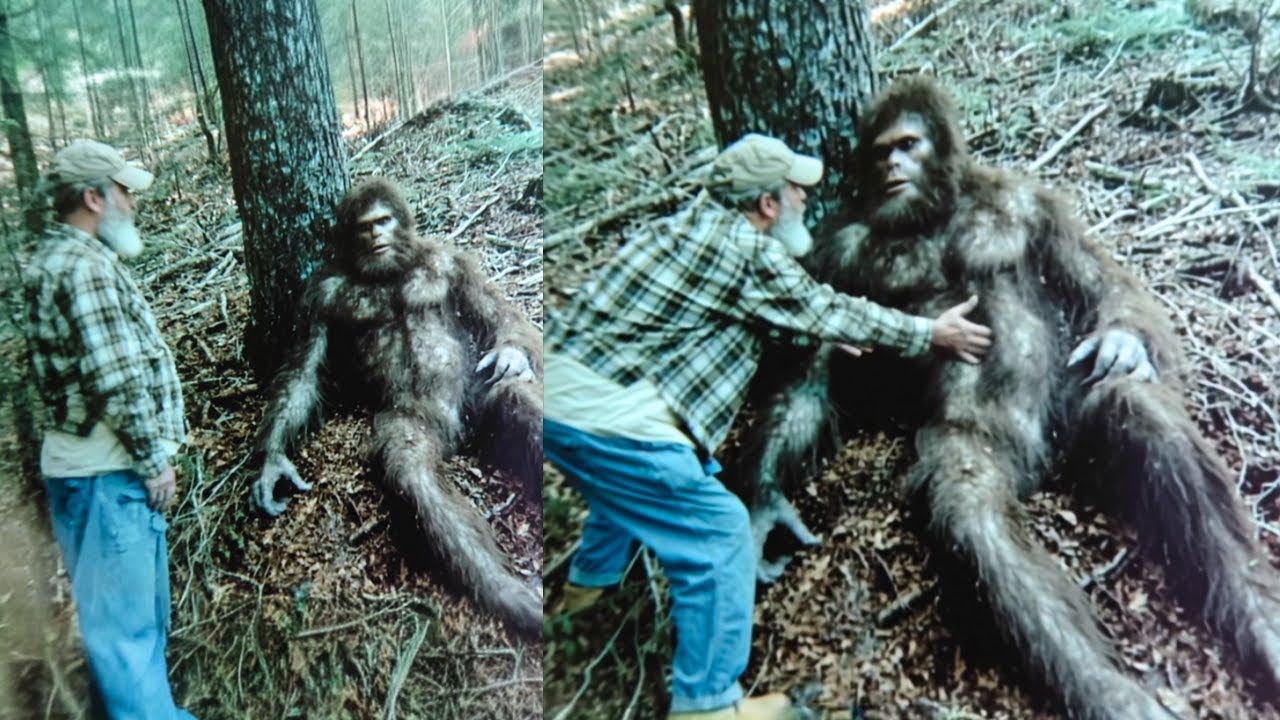

He Found Dy/ing Bigfoot in the Forest, Its Last Words About Humanity Will Sh0ck You –

Observer of the Last Forest

I’d hunted in those mountains for twenty years. I knew every track, every sound, every subtle shift in the wind that meant an elk herd had moved through or a cougar was watching from the shadows. The Cascades had raised me, broken me, and, in their own way, kept me alive.

But on that cold morning in 1997, I found footprints unlike anything I’d ever seen.

They changed everything.

I. The Tracks

My name is Mark Walker. I’m forty‑two years old and, for the past four years, I’ve been living alone in a one‑room cabin outside Crescent Lake, Oregon. Most people in town know me as the quiet guy who brings in deer and elk to the local butcher. The one who nods politely, pays in cash, and leaves before conversation can really begin.

They don’t know about the twelve years I spent in the army. They don’t know about the jungles in Central America, about the night I carried my best friend’s broken body through eleven hours of hell only to watch him die on the medevac helicopter.

They don’t know that whatever was left of the original Mark Walker died the same night Danny Rodriguez did.

That November morning started like every other. I woke at 5:30 in my small cabin, made coffee in the old Mr. Coffee machine—my only real luxury purchase in years—and checked my gear. My Remington 700 was clean and ready. I maintained my rifle with the same discipline the army had beaten into me, even though I couldn’t maintain much else in my life.

I was heading up to the northern ridge where I’d spotted elk sign two days earlier. Hunting season was coming; I needed to scout the territory.

The drive up the logging road took forty minutes in my ’89 Ford F‑150, the truck rattling over ruts and washouts the timber companies had stopped maintaining long ago. The radio was nothing but static that far from town, so I drove in silence, watching mist curl between the Douglas firs like something alive.

At the end of the road, I parked and shouldered my pack. Rifle, water, first aid kit, rope, compass, topographic map in a waterproof case—old habits from my military days. A Motorola pager rode on my belt, though it rarely went off. Only the butcher had the number, and he didn’t call often.

The climb to the ridge was steep but familiar. My father had taught me to track in these mountains—how to read the forest, how to move quietly, when to trust your instincts and when to trust your compass. He’d been a logger and a hunter. He’d been dead fifteen years.

Sometimes I wondered what he’d think of what I’d become: a ghost in the woods, more comfortable with silence than people.

Two hours into the hike, I found the tracks.

At first, I thought they were bear prints. They were sunk deep in soft mud beside a seasonal creek, clear as ink on paper. I crouched to get a better look.

The details didn’t fit.

The print was huge—at least seventeen inches long—but it wasn’t a bear’s paw. Five distinct toes. Not claw marks, not the spread of a front paw, but toes arranged like a human foot. A human foot scaled up and then some. The depth of the impression said whatever made it was incredibly heavy. The stride length between prints was easily five and a half feet.

Growing up in Oregon, you can’t avoid Bigfoot stories. Campfire tales, grainy photos, drunk hikers swearing they’d seen something. I’d always filed it with UFOs and lake monsters—entertaining nonsense.

But those tracks were real. Fresh. Maybe six hours old.

And they led uphill, away from any trail, into country so remote most hunters never bothered with it.

I should’ve marked the spot and moved on. I should’ve stuck to my plan: scout elk, get home before dark, drink cheap coffee and pretend the silence in my cabin was a choice.

Instead, I followed the tracks.

Curiosity overrode sense. Maybe it was more than curiosity. Maybe it was that numb part of me, the part that had gone quiet the night Danny died, stirring for the first time in four years.

The tracks led me off established game trails into old‑growth forest. Under the dense canopy, the undergrowth thinned and walking grew easier. I moved automatically into my old patrol rhythm: step, pause, listen, scan. Repeat. The forest was unusually quiet. No birds. No squirrels. Just the whisper of wind in high branches and my own controlled breathing.

An hour into tracking, I saw the first drop of blood.

Dark and fresh on the moss. Then another. And another. A scattered trail that ran alongside the footprints.

Whatever I was following was bleeding.

My pulse picked up—not from fear, but from something older, deeper. Combat awareness. An injured animal is unpredictable. A cornered, wounded thing is the most dangerous creature in the world.

I should’ve been more cautious.

Instead, I pressed on.

The blood grew more frequent, the droplets larger. The tracks led to a rocky outcrop surrounded by ancient cedars. There, the trail ended at a shallow cave—a low overhang formed where two massive boulders leaned against each other.

I saw it in the shadows.

At first my brain refused to process the shape. Too big. Wrong proportions. Then it moved slightly, and the world snapped into a new, impossible focus.

A Bigfoot.

A real, living Bigfoot.

It lay on its side, massive chest rising and falling in slow, labored breaths. Even curled up, it was enormous—easily over seven feet tall, maybe seven and a half. Dark brown hair covered its body, matted with blood along its left side. Its face was turned away, half in shadow, but I could see the heavy brow, the powerful jaw, the broad nose.

I stood motionless, rifle half raised, my mind racing. Every rational thought insisted this was impossible. Folklore. Hoax. Misidentification.

But the thing on the ground was real. And it was dying.

You know the look when you’ve seen enough death. I’d seen it in jungles, in field hospitals, in Danny’s eyes on that helicopter. The shallow, irregular breathing. The stillness that isn’t rest but exhaustion. A body on the edge of giving up.

This creature had the same look.

Slowly, I lowered my rifle.

Its eyes opened.

Deep brown. Not animal‑bright, not glassy with panic, but focused. Aware. They locked onto mine. My legs wanted to run. My hands wanted to raise the rifle again.

It didn’t move to attack. It just watched me.

And in those eyes, I saw pain. Resignation. Acceptance.

And something else.

Recognition—like it had been expecting me.

“Easy,” I heard myself say, voice rough from disuse. “I’m not going to hurt you.”

It made a low sound. Not a growl exactly, but nothing human either. It shifted slightly, and I saw the wound clearly: a massive gash along its ribs, deep and ragged.

Not from a bullet. More like it had fallen—maybe onto a broken branch or sharp rock. The bleeding had slowed but not stopped. On a human, this would require immediate surgery.

Here, miles from any road, it was a death sentence.

I shrugged off my pack, moving slow, my hands where it could see them. It watched but didn’t try to crawl away. Didn’t lunge. Didn’t even flinch.

I dug out my first aid kit, painfully aware how inadequate it was. Gauze. Tape. A small bottle of antiseptic. Enough for a bullet wound, maybe. Not enough for this.

“I’m a medic,” I said, my voice quieter. “Well. I was. A long time ago. I’m going to try to help. Okay?”

I didn’t expect it to understand. Sometimes you talk just to fill the silence.

It made another sound—softer, almost questioning. Then, incredibly, it shifted, turning just enough to give me better access to the wound.

It was trusting me.

My hands shook as I opened the kit. Up close, the wound was worse than I’d thought. Muscle torn. Bone maybe chipped. Infection already starting around the edges.

“This is going to hurt,” I warned as I poured antiseptic into the wound.

It tensed, jaws clenched, but made no move to stop me. I packed the wound with every scrap of gauze I had and wrapped its torso with tape and strips of rope, improvising the best field dressing I could manage.

It wasn’t nearly enough. We both knew it.

When I finished, I sat back on my heels, studying the impossible being in front of me. Up close, I could see silver hairs threaded through the brown, deep lines etched around its eyes, the weariness in its face.

“How old are you?” I asked, not expecting an answer.

It looked at me for a long moment.

Then, in a deep, resonant voice, in slow, careful English, it said:

“Hundred… and two… years.”

I nearly fell over.

“You… can talk,” I managed. “You understand me?”

Its lips pulled back slightly, showing worn, flat teeth. A smile?

“I have listened… to your kind… for many years,” it said. “Learned… words.”

Each word came slow, like lifting a weight.

“The wound—” I started.

“Too late,” it rumbled, head moving in the smallest of shakes. “I am old. This body… finished.”

It took a labored breath.

“But I am glad… you came.”

“Why?”

“Because… I have something to say… about your kind.” It closed its eyes briefly as if gathering strength. “And someone… must hear.”

I set my rifle aside.

And I listened.

II. The Observer

“What do I call you?” I asked. “Do you… have a name?”

Its eyes opened again. It studied me.

“My people… do not use names… like yours,” it said at last. “But… the old ones… who lived before me… they called me… Observer.”

“Observer,” I repeated.

The name fit. Those deep brown eyes looked like they’d been watching for a very long time.

“I’m Mark,” I said, feeling bizarrely self‑conscious about introducing myself to a dying Bigfoot. “Mark Walker.”

“Mark,” it repeated, the word coming out softer than my own pronunciation. “You are… hunter.”

“Yes,” I admitted. “Though I wasn’t hunting you. Didn’t even believe you existed until about twenty minutes ago.”

A flicker of amusement passed through its eyes.

“Most of your kind… do not believe,” Observer said. “That is our advantage. Our survival.” Another breath. “But now… it does not matter. Soon… I will be gone. My people… are already ghosts.”

“There are others? More of you?” I asked.

“Few,” Observer said. “Very few. Once… when I was young… there were more. But we… do not breed often. And your kind… spreads everywhere. Takes everything.”

The words weren’t accusatory. Just factual.

I pulled out my water bottle and offered it. Observer studied it, then took it with surprising delicacy, those massive fingers careful not to crush the plastic. It sipped twice and handed it back.

“Thank you,” it said.

“You said you had something to tell me,” I prompted gently. “About humanity.”

Observer nodded slowly.

“I have watched your kind… for one hundred and two years,” it said. “Watched you grow… spread… change. I have seen… three great wars. Seen your machines… become like magic. Seen your numbers… multiply like rabbits.”

Its voice grew a shade stronger as it spoke, like the urgency itself kept it going.

“And I have seen… what you do not see… about yourselves.”

“What’s that?” I asked quietly.

Observer’s gaze drifted upward to the canopy.

“When I was young,” it said, “your kind traveled… on horses. Used simple tools. Cut trees… with hand saws. The forest… could heal… faster than you could wound it. I thought… you were like us. Take what you need… but no more.”

It looked at me again.

“But you are not… like us.”

“We’ve gone too far,” I said.

“Too far,” it agreed. “First, you needed wood… for warmth… for shelter. Understandable. Then… you wanted more wood… for money. For… what did I hear it called… economy.”

The unfamiliar word came out heavy and awkward.

“You cut faster… than trees can grow. You build roads… everywhere. You fill the sky… with poison… from your machines.”

I wanted to defend us. Talk about medicine, technology, art. But sitting beside a dying being that had watched us for a century, all the arguments felt hollow.

“I watched… the first automobile… come to these mountains,” Observer said. “1917. Loud… smoking thing. I thought… it was sick. But no. That is how… all your machines work. Taking ancient life… from deep in the earth… burning it… filling the air… with death.”

It shifted and winced.

“I watched the loggers come. First… a few men… with axes. Then bigger groups. Then machines. Chainsaws that scream… like demons. In my life… I have watched… ninety percent… of the old forest… disappear. The grandmother trees… that stood… for a thousand years… gone in minutes.”

“I know,” I said. I’d seen the clear‑cuts—whole mountainsides shaved bald. It had always bothered me, even as a hunter who used the forest.

My knowing didn’t seem to help much.

“Yes,” Observer said. “But here is… what terrifies me. What I must tell you… before I go.”

Its eyes fixed on mine, and there was something like urgency in them that made my skin prickle.

“Your kind knows.”

“Knows what?” I asked.

“Knows what you are doing,” Observer said. “I have heard… your scientists. Listened to your radio… your boxes people carry. They say… the air is warming. The ice… is melting. The animals… are dying. They warn you.”

“Climate change,” I said. “Yeah. They’ve been talking about it more.”

“And yet,” Observer whispered, “you do nothing. You know… the cliff is ahead. You see it coming. And you drive… faster.”

Its eyes glistened. Whether from pain or something like sorrow, I couldn’t tell.

“That is… what terrifies me,” it said. “Not that you destroy… by accident. But that you destroy… knowing. Choosing.”

I felt the words like a punch. Because they were true. We did know. We’d heard the warnings for decades and kept on burning, cutting, building, consuming.

“My people… die… because you leave us… no room,” Observer said. “But you… you die… because you cannot stop… eating your own world. That is the terrible truth. You are… smart enough to see… but not wise enough… to change.”

We sat in silence, my heart pounding in my chest. Here was a creature that had survived by staying hidden, by taking little, by living in balance. Watching us burn through everything in a single lifetime.

“Is that why you wanted to talk to me?” I asked. “To tell me we’re doomed?”

“No,” Observer said. For the first time, its voice softened. “I wanted… to tell you… because you are different.”

“Different how?”

“You carry death… inside you,” it said. “I see it. I smell it. Not sickness… but grief. Loss. You have watched… someone die. Someone you loved.”

My throat closed. I hadn’t spoken Danny’s name out loud in four years.

“My best friend,” I said hoarsely. “Danny Rodriguez. He died in my arms.”

“Yes,” Observer said gently. “You carry him still. That weight… makes you different. Makes you see… that life is precious. That time is short. That taking and taking and taking… leaves you empty.”

It took a shaky breath.

“Your kind is young,” Observer said. “Young species… like young people… think they will live… forever. Make mistakes… because they cannot imagine… the end.”

“But you… you have touched death. You know… the end comes.”

I wiped at my eyes, surprised to find them wet.

“And what am I supposed to do with that?” I asked. “Knowing doesn’t change much.”

“Remember,” Observer said simply. “Remember what I tell you. Remember… that old one… who lived one hundred and two years… watched your kind… rush toward cliff… and begged you… to turn around.”

Its breathing was rough now, each word carved out of effort.

“Tell others,” it rasped. “Plant seeds. Maybe they will not grow in time. Maybe your kind… is already past… saving. But maybe… maybe not.”

“I’m just one person,” I said. “I live alone in the woods. I barely talk to anyone. Who’s going to listen to me?”

“You were soldier,” Observer said. “You know… about missions. About doing… your part… even when outcome… uncertain.”

Its massive hand lifted, trembling, and settled on my shoulder. The weight was immense but gentle.

“This is… your mission now,” it said. “Carry my words. Tell them… old one watched… and warned. Tell them… it is not too late… to choose differently.”

The hand slipped from my shoulder and fell to the ground. Observer’s chest rose and fell shallowly. The light in its eyes dimmed.

“Wait,” I said. Panic flared. “I have questions. About your people. How you live. How you stayed hidden all this time—”

“No time… for questions,” Observer murmured. “Only time… for truth. Truth is simple.”

It fixed me with one last, piercing look.

“Your kind… has greatness in it,” it said. “I have seen… your music… your art… your capacity… for love… for sacrifice. You are not evil. Just young. Foolish. Afraid.”

“Afraid of what?” I whispered.

“Of changing,” Observer said. “Of giving up… comfort. Of admitting… you were wrong. But change… is only path forward. Either you change… the way you live… on this earth… or the earth… will change you… through suffering… through loss… through death… of everything… you love.”

Its eyes slipped closed, then opened again with obvious effort.

“Promise me,” it whispered. “Promise… you will remember. Promise… you will try.”

“I promise,” I said, voice breaking. “I swear it. I’ll remember. I’ll try.”

Observer’s face eased, something like peace in its expression.

“Good,” it breathed. “That is all… I can ask. One human… who hears… who understands… who might plant seed… that grows… after I am gone.”

It exhaled in a long, rattling breath.

“I am ready now,” it said. “Ready… to rest.”

“Is there anything I can do?” I asked helplessly. “Anything to make you more comfortable?”

“You already did,” Observer whispered. “You stayed. You listened. You cared. That is more… than I expected. More than… most of your kind… would give.”

Its breaths came farther apart.

“Mark Walker,” it said, barely audible. “Thank you… for bearing… my final words. Use them… wisely.”

“Observer,” I said softly. “I’m sorry. For what my kind has done. For what we’re doing. For what you had to watch.”

Its eyes opened one last time. No anger. No bitterness.

“Not alone,” it breathed. “You are here. That matters. Everything… matters.”

Those were its last words.

Its chest rose once, held, then fell.

Then nothing.

The forest grew very still.

III. The Promise

I sat there for a long time, my hand resting on Observer’s shoulder as its body cooled under my palm. I’d cried exactly once in the four years since Danny died—at his funeral, briefly, before I jammed the grief into some dark corner and fortified the walls.

Now those walls cracked.

I wept—for the creature in front of me, for Danny, for the forests stripped bare, for a world sprinting toward a cliff while pretending the air was fine.

When I could finally stand, the sun had shifted far across the sky. I’d been there for hours.

Looking down at Observer’s body, I knew I couldn’t just leave it. I couldn’t risk some hunter stumbling on it, dragging it out, turning it into a trophy or a sideshow or a lab specimen.

It had trusted me with its last hours. The least I could do was give it dignity in death.

I spent the rest of the afternoon building a cairn. Hauling stones and branches, stacking them over the body until the massive form was completely covered. The work was brutal, made worse by the tears that kept blurring my vision, but I didn’t stop until the job was done.

The cairn wouldn’t last forever. Nothing does. But it would last long enough for nature to reclaim what had been hers all along.

I placed the last stone and spoke aloud, feeling foolish and like it mattered anyway.

“I’ll remember, Observer,” I said. “I’ll carry your words. I’ll try to make people understand. I don’t know if it’ll matter, but I’ll try.”

The wind stirred the cedars overhead. For a second, it felt like an answer.

The hike down took twice as long. My legs were heavy. My mind was somewhere else, replaying Observer’s words, that ancient gaze, the terrible, simple truths.

By the time I reached my truck, the sun had fallen low, painting the sky in oranges and purples that felt almost offensive in their beauty. The world was unchanged.

But I wasn’t.

You can’t sit with a dying creature that has watched your whole species for a century and come away the same.

I drove back to the cabin on autopilot. Once inside, the place felt smaller than usual. One bed. One table. A shelf of books. A wood stove. A life stripped to bare function. Before, it had felt like refuge.

Now it felt like hiding.

I didn’t eat. I didn’t sleep. I sat at my tiny table, pulled out the notebook I usually used for tracking game and weather, and began to write.

Everything Observer had said. Every word I could remember. Every pause, every emphasis.

By midnight, I had seven pages of cramped handwriting—and it still felt like I’d captured only a shadow. How do you put the weight of a century’s observation into ink? How do you assign words to the look in those eyes?

I read it over and over. Observer’s message was clear: we knew what we were doing. We knew the cliff was there. We were driving faster anyway.

And somehow, I—a broken ex‑soldier living on the edge of nowhere—was supposed to make people care.

It felt impossible.

But I’d made a promise.

IV. Seeds

The next morning, I did something I almost never did: I drove into town and parked in front of the public library.

The librarian, a woman in her sixties named Margaret Chen, looked up as I walked in. I’d used the photocopier there twice in four years. That was the extent of our relationship.

“Mark Walker,” she said, with real warmth. “What brings you in today?”

“I need to research something,” I said. “Climate change. Deforestation. Environmental science. That kind of thing.”

Her eyebrows rose. She didn’t ask why. Just led me to the shelves and started pulling books, journals, reports.

“Our collection’s not huge,” she said, “but it’ll get you started.”

I spent four hours in a hard chair under fluorescent lights, buried in data. Reports from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Articles on deforestation rates, species extinction, ocean acidification, projected temperature rise, sea level, ecosystem collapse.

The numbers were worse than anything Observer had said aloud. The science was blunt. The trends were clear. The timeline was short.

We knew.

Around noon, Margaret brought me a cup of coffee and a sandwich.

“You’ve been at it for hours,” she said. “Fuel’s on me.”

“Thank you,” I said, genuinely surprised.

She hesitated. “What sparked this sudden interest?” she asked gently.

I almost lied. Almost said “just curious.” Instead:

“I saw something in the woods yesterday,” I said slowly. “Something that made me realize I’ve been asleep.”

She studied me for a long moment, then nodded.

“I know that feeling,” she said. “I taught in Portland for thirty years. I watched kids grow more disconnected from nature every year. Watched environmental programs get cut from schools. Everyone focused on jobs and test scores and… economy. We forget we’re part of something bigger.”

“Do you think people can change?” I asked. “Really change? Not just talk about it?”

“Some can,” she said. “Most won’t. Not until they’re forced. Humans are very good at ignoring problems until they’re crises.” She smiled, small but sincere. “But that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t try. Every person who wakes up—that matters.”

“Observer said something like that,” I muttered, before catching myself.

“Observer?” she asked.

“Someone I met,” I said quickly. “Someone very old, very wise.”

She didn’t push. “I’m glad you’re here, Mark,” she said instead. “Reading is the first step. Thinking is the second.”

Over the next week, a new routine emerged. Mornings I hunted, fixed things around the cabin, did the work that kept me fed. Afternoons I spent at the library, reading everything I could on environmental collapse. Evenings I sat at the table, trying to figure out how to turn Observer’s words into something another human might hear without shutting down.

The problem was simple: I didn’t know how to talk to people anymore.

On the eighth day after Observer’s death, I was dropping off two deer at the butcher shop when Bill Henderson wiped his hands on his apron and asked:

“Mark, you know anything about tracking?”

“Some,” I said.

Which was an understatement. In the army, I’d been one of the best. But I’d learned not to advertise skills.

“My nephew’s in the Boy Scouts,” Bill said. “Their usual wilderness guy moved away. They’re looking for someone to teach tracking and survival. I thought of you.”

Old instincts told me to say no. Keep my head down. Avoid entanglements—especially with kids.

But Observer’s voice lingered.

Plant seeds.

“When?” I heard myself ask.

Bill’s face lit. “Saturday mornings. Community center. I can give you the scoutmaster’s number.”

“Okay,” I said, nerves twisting in my gut. “Yeah. I’ll do it.”

V. Teaching the Young

That Saturday, I stood in front of twelve boys between eleven and fourteen. They sat in a semicircle in the community center’s multipurpose room, some slouched, some eager, all watching the quiet stranger they’d been told was an “experienced outdoorsman.”

Their scoutmaster, Robert Torres, introduced me and stepped aside.

I cleared my throat.

“I’m Mark Walker,” I said. “I’m going to teach you how to read the forest: tracks, scat, broken branches, sounds. How to move quietly. How to see what most people miss.”

A hand shot up immediately.

“Have you ever tracked anything dangerous?” a boy asked. “Like a bear or a cougar?”

“Yes,” I said. “Both.”

I hesitated. Then, before I could stop myself:

“And something most people don’t believe exists.”

Every head snapped up.

“What was it?” another boy asked.

I thought of Observer. Of the promise. Of seeds.

“I’ll tell you,” I said, “but first you need to understand something. The wilderness isn’t just a big playground or a warehouse full of resources. It’s home. To animals that were here long before us. That have as much right to be here as we do.”

Silence. Even Robert seemed unsure where this was going.

“Right now,” I continued, “we’re taking that home away. We’re cutting down forests, polluting air and water, changing the climate. We’re doing it so fast the animals can’t adapt. Some of them are disappearing. Forever.”

Some faces showed confusion. Others showed interest. No one looked bored.

“Last week,” I said, “I tracked something into the mountains—something I didn’t believe in. And I found it dying. Not just from a fall, but from losing its home. From having nowhere left that was safe from us.”

The first boy leaned forward. “What was it?”

“You’d call it Bigfoot,” I said. “I called it Observer. And before it died, it told me things about humanity that you need to hear. Because you’re the ones who will live with what we do.”

One of the older boys snorted. “You expect us to believe you met Bigfoot?”

“I don’t care if you believe me,” I said. “What matters is the message. Whether it came from a Bigfoot, or an old man in the woods, or a voice in my head, the truth doesn’t change.”

I told them the short version: Observer’s hundred‑plus years of watching humans, the loss of old forests, the machines, the warming climate, the terrible fact that we were destroying the world knowingly.

A younger boy—maybe eleven—raised his hand.

“If the Bigfoot was real,” he said, “and it lived that long and saw all that stuff… what did it want us to do?”

I felt my throat tighten.

“It said we’re not evil,” I replied. “Just young and scared. Scared of change. Scared of admitting we were wrong. Scared of giving up comfort.”

I looked each of them in the eye.

“It wanted you to remember. To pay attention. To be the generation that chooses differently.”

The room was quiet.

“So,” I said, “who wants to learn how to read tracks?”

Every hand went up.

The Saturdays became a ritual. I taught them animal prints in the dirt behind the community center, then in real forests around Crescent Lake. I showed them how to age tracks by crispness and debris, how to tell deer from elk, coyote from dog. How to see the forest not as a backdrop but as a living network.

Between lessons, I slipped in other things. How clear‑cuts affected streams. How losing one species rippled outward to others. How the weather was changing, and what the scientists were saying.

Some kids thought I was crazy. Some boys complained to their parents that I wouldn’t shut up about the environment. But a core group stayed curious.

One of them was Michael Santos, thirteen, small but sharp. After our third session, he approached me as the others piled into pickup trucks.

“Mr. Walker,” he said, voice low, “I’ve been thinking about what you said. About Observer. About us destroying everything.”

“Yeah?” I asked.

“My dad works for Cascade Timber,” he said. “He cuts trees. I heard him and his friends talking. They’re mad at environmentalists. They say if they shut down logging, people lose jobs.”

He swallowed.

“But when you show us what’s being lost… it makes me wonder if maybe the environmentalists are right. Does that make me a bad son?”

I stopped packing gear and looked him in the eye.

“No,” I said. “It makes you honest.”

I took a breath.

“Your dad isn’t a bad man for logging. He’s supporting his family. The problem isn’t people like him. It’s a system that makes him choose between his job and the forest’s survival.”

“So what do we do?” Michael asked. “If we stop logging, people lose jobs. If we keep logging, we lose the forest.”

“That’s the trap,” I said. “We’ve been told it’s either jobs or environment. Like those are the only choices. But what Observer showed me is: the real question is whether we can live differently. Log slower. Smarter. Create jobs that restore instead of destroy.”

“Can we?” he asked.

“I don’t know,” I said. “But I know we have to try. Because the path we’re on ends with no jobs and no forests.”

He nodded.

“Will you tell me more about Observer?” he asked. “About what it saw?”

“Yeah,” I said. “I will.”

Word spread, like it does in small towns.

The weird loner who claimed to have met Bigfoot was teaching Boy Scouts about the environment.

Some people were supportive. Bill’s nephew suddenly wanted to study biology. Margaret began showing up to sessions with books and articles. Robert remained cautiously neutral.

Others weren’t so thrilled.

VI. Trouble in Town

It came to a head at the diner three weeks later. I’d just finished breakfast when a big man with a red face and hands like shovels planted himself by my table.

“You Walker?” he demanded.

“That’s me,” I said.

“Name’s Dale Pritchard,” he said. “Timber supervisor. You’re the one telling those boys their fathers are killing the planet.”

“I never said that,” I replied.

“My son came home asking if I’m destroying the Earth,” Dale said, voice loud enough to turn heads. “He’s twelve. Twelve. You did that.”

“I said we’re making choices that have consequences,” I said, staying seated. “There’s a difference.”

“Don’t play word games with me,” he snapped. “You’re spreading propaganda. Filling kids’ heads with lies. We replant. We follow regulations. We’re not the villains you make us out to be.”

“A tree farm isn’t a forest,” I said. “It doesn’t hold the same life. Doesn’t store as much carbon. Doesn’t replace thousand‑year‑old systems.”

He glared.

“You think you know more about these woods than men who’ve worked them their whole lives?” he asked. “You’re just some burned‑out soldier hiding in a shack. You don’t know what it means to support a family.”

Something cold settled in my chest.

“I know about survival,” I said quietly. “I carried my best friend through the jungle while he bled all over me. He died anyway.”

The diner went silent.

“Before he died,” I said, “he told me: Make it count, Mark. Make the time you have count.”

I stood, leaving my plate half‑finished.

“For four years, I didn’t,” I said. “I hid. Then I met something that had watched us for a century. It told me we’re killing the only home we have, and we’re doing it with our eyes open. So yeah, I’m telling kids to pay attention. To think beyond the next paycheck.”

I looked him in the eye.

“If that makes me a troublemaker, I’ll live with it.”

I dropped money on the counter and walked out with my heart pounding and my hands shaking.

That afternoon, I hiked back up to Observer’s cairn.

Someone else was there.

VII. The Old Ones’ Land

An elderly Native American woman sat cross‑legged near the cairn, eyes closed, hands resting lightly on her knees. Her gray hair hung in two long braids down the front of her dark jacket. She wore no feathers, no costume—just layers of wool and weathered skin.

I stopped at the edge of the clearing, unsure.

Without opening her eyes, she spoke.

“You’re the one who built this.”

It wasn’t a question.

“Yes,” I said. “I found someone here. Someone who died.”

She opened her eyes and looked at me—not with surprise, but with the tired recognition of someone who has been expecting something for a long time.

“My name is Sarah Whitebear,” she said. “Klamath tribes. This is our land, though the government has a different map.”

She nodded at the cairn.

“One of the old ones died here,” she said. “You did a good thing. Honoring them.”

My heart hammered. “You… know what I found?”

“My people have always known the forest people,” she said. “We call them Tsi‑qwis. They were here before us. They should have been here after us, too.” Her eyes softened. “Word travels. We heard that a white man sat with an old one as it died. Listened. Covered the body with care. That is rare.”

“It asked me to remember,” I said. “To carry its words. About us. About what we’re doing.”

“And are you?” Sarah asked. “Carrying them?”

“I’m trying,” I said. “Teaching kids. Reading. Talking to people who don’t want to listen. It feels like trying to stop a river with my hands.”

“You’re asking the wrong question,” she said. “The question isn’t ‘How can one man change everything?’ The question is ‘What is my part?’”

She stepped closer, and there was nothing fragile in the way she moved.

“You don’t have to save the world, Mark Walker,” she said. “You just have to do your piece.”

“Observer called it planting seeds,” I said.

She smiled. “That’s a good way to put it. My people have been planting seeds for five hundred years. Most didn’t grow. We keep planting.”

She reached into a leather pouch and withdrew a small, cloth‑wrapped bundle. She unwrapped it to reveal a carved wooden pendant on a leather cord: a circle with symbols I didn’t recognize.

“This is a blessing,” she said. “For a safe journey. For the old one.”

She laid it carefully on top of the cairn, then murmured words in her own language, soft and melodic.

“The old ones are dying,” she said when she finished. “Not just from age. From grief. From watching everything they knew vanish.”

She studied me.

“Before they go, some are talking,” she said. “To people like you. People who might listen.”

“What should I do?” I asked. “Beyond teaching scouts and arguing in diners?”

“What you’re already doing,” she said. “Teach. Speak truth. Plant seeds. And connect with others. There are more of us than you think. Scientists. Tribal leaders. Activists. Even some loggers. They are all fighting different fronts of the same war.”

She pulled a folded paper from her pocket and handed it to me.

“There’s a gathering next month in Eugene,” she said. “Environmental groups, tribes, scientists. They’re organizing to fight a big logging expansion in the Cascades. You should come. Bring your story.”

“No one will believe me,” I said.

“Some will,” she said calmly. “Some won’t. The ones who need to hear it will be listening. That’s enough.”

She turned to go, then paused.

“The old one chose well,” she said. “You’re broken enough to understand loss, strong enough to carry weight, stubborn enough not to quit when it gets hard. Those are the ones who make a difference.”

“I’m scared,” I admitted. “Scared I’ll fail. Scared it’s already too late.”

“Of course you’re scared,” Sarah said. “Anyone with sense is. Courage isn’t the absence of fear. It’s walking anyway.”

She left me there with the cairn and the wind and the weight of a mission I’d never asked for.

I looked at the pendant on the stones.

“I’m doing my part,” I said quietly. “I hope it’s enough.”

The wind whispered through the cedars.

I chose to hear it as approval.

VIII. The First Gathering

The community hall in Eugene smelled like coffee, rain, and paper. About a hundred people milled around: environmental activists, tribal representatives, scientists with slide decks, journalists with press badges.

I hovered near the back, wondering if I could still walk out.

Sarah appeared at my elbow like she’d stepped out of the trees.

“You came,” she said. “Good.”

“I promised,” I replied.

She smiled, then started introducing me to people: Dr. Elizabeth Mora, wildlife biologist, documenting species decline in the Cascades. James Riverwind, Warm Springs elder, fighting logging expansion for decades. A rail‑thin lawyer from an environmental nonprofit. A young journalist. More names and faces than I could retain.

If there was a common thread, it was this: they all looked exhausted. Not from lack of sleep, but from years of fighting uphill.

The presentations started at ten. Graphs and charts. Old growth forest cover dropping. Species lists shrinking. Temperature curves rising. All the numbers lined up with what I’d read at the library.

There was anger in the room. Grief. But also determination. These people hadn’t given up.

During lunch, Sarah sat beside me with a paper plate of food.

“This afternoon there’s an open mic,” she said. “People sharing why they’re here. I think you should speak.”

My stomach clenched.

“I’m not a speaker,” I said. “And the Bigfoot thing…”

“Some will think you’re crazy,” she said. “Some already think everything we do is crazy. But others will understand. They need to be reminded this isn’t just about laws and statistics. It’s about living beings. Real loss.”

I thought of Observer, dying on the cold rock.

“Okay,” I said. “I’ll try.”

When my name was called, my legs felt heavier than they had on any mountain. I walked to the front, notebook in hand, heart pounding.

“My name is Mark Walker,” I said into the microphone. “Six weeks ago, I didn’t believe in Bigfoot. Or much of anything, really.”

A few people chuckled. A few rolled their eyes.

“I was just existing,” I said. “Hiding in the woods. Avoiding people.”

I told them about the tracks. About the cave. About the wound. About the voice that had learned English by listening from the trees for decades.

I read from my notebook—or tried to. My hands weren’t steady, but the words were there. Observer watching horses become cars. Axes become chainsaws. Clear‑cuts devouring old forest. The terrible truth that we weren’t doing this by accident.

“I don’t care if you believe me about Bigfoot,” I said finally. “You can think I’m crazy. What matters is the message.”

I looked out over the room.

“We know,” I said. “We know the forests are dying. The climate is changing. Species are disappearing. We know. And we keep going as if someone else will fix it later.”

I closed the notebook.

“Observer died after a hundred and two years of watching us,” I said. “It died asking me to plant seeds. To tell others. To at least try.”

Silence filled the hall.

Then one person started clapping. Then another. And another. Not everyone. Some still looked skeptical. But enough.

Afterward, people came up to talk. Dr. Mora told me my story reminded her why she began her work—not for data, but for the animals themselves. James shared stories of forest people from his own tradition. An activist asked if I’d be willing to speak at other events.

I left with a folder full of contacts, reports, and invitations—and something else I hadn’t expected:

The sense that I wasn’t alone.

IX. Doing My Part

The next weeks blurred into motion.

I kept teaching the scouts. The group grew as kids brought friends. We started talking explicitly about climate, habitat, sustainable practices. I brought in articles. Margaret lent us books.

Patricia, Margaret’s daughter—the one from the Sierra Club—drove up from Eugene and started working with me on environmental education modules for the local schools.

I began attending town council meetings. At first, I sat in the back. Then I started speaking. Not with Observer’s voice, but with my own. I shared data I’d collected, stories from the gathering, the seventh‑generation principle Sarah had taught me.

The breakthrough I didn’t expect came from Dale.

His son was in my scout group. The boy had been asking questions at home he couldn’t easily dismiss. Dale called me, said he wanted to “straighten something out.” I expected another shouting match.

Instead, we spent three hours at his kitchen table talking about logging.

“My grandfather cut these forests,” Dale said. “He did it slow. Took what he needed. The trees grew back.” He tapped the table. “Then the big outfits came in. Clear‑cutting. Short rotations. Quotas. You miss your numbers, you’re out. No one cares what the mountains look like in fifty years.”

“So what do we do?” I asked.

“We fight for different rules,” he said. “Longer rotations. Smaller cut blocks. Mandatory old‑growth reserves. It’ll mean fewer jobs for a while. But those jobs will still exist in thirty years.”

He surprised himself by asking to come talk to the scouts. He stood in front of them one Saturday and told them about good logging and bad logging. About how a working forest can be healthy or ruined.

He became one of our strongest allies in pushing back against the worst logging proposals.

Three months after Observer’s death, I hiked back to the cairn in winter. Snow muffled every sound. I brought a letter I’d written—pages of updates about everything that had changed.

I read it aloud.

“I don’t know if you can hear me,” I said. “But I kept my promise. I remembered. I carried your words. I planted seeds.”

The trees creaked softly in the cold.

“The cliff is still ahead,” I said. “We’re still driving. But some of us are braking. Some of us are trying to turn the wheel.”

I stood there in the still white silence and felt something I hadn’t felt since before Danny died: purpose.

Not peace in the sense of “everything is okay.”

Peace in the sense of “I know what I’m meant to do, and I’m doing it.”

X. The Town Hall

Six months after Observer died, a proposal came through that would have gutted the last significant old‑growth section near Crescent Lake. Ironically enough, the same mountains where Observer and I had met.

The town hall meeting was packed. Loggers and their families sat on one side. Environmentalists and concerned citizens sat opposite. Tribal representatives, teachers, students, business owners—all squeezed into the same room, separated by more than just an aisle.

I’d been asked to speak by both sides.

I walked to the microphone and saw faces I knew now. Dale, arms crossed, watching. Margaret. Patricia. Sarah with other tribal representatives. Michael, sitting between his parents.

“Six months ago,” I said, “I met someone in those mountains. Someone who had lived there more than a century. Someone who’d watched those forests stand and fall.”

I told them about Observer again. Not in mystical terms, but as an ancient witness. I shared its simple questions: what kind of species knows it is destroying its own life support system and keeps going anyway?

“The question tonight isn’t just about this logging plan,” I said. “It’s about what kind of people we want to be.”

I looked at the loggers.

“The people cutting these trees are not villains,” I said. “They are skilled workers. Parents. Neighbors. Their jobs matter.”

I looked at the environmentalists.

“The people fighting to save this forest aren’t naïve,” I went on. “They understand that old growth, once gone, can’t simply be replanted. Some things you can’t replace.”

“The real problem,” I said, “is a system that tells us we can only have one or the other.”

I pulled the pendant Sarah had placed on the cairn from my pocket and held it up.

“There’s an idea in Native tradition,” I said. “Decide with the seventh generation in mind. Ask what this choice will mean for your great‑great‑great‑great‑grandchildren.”

I let that hang.

“Do we want to be the people who cut down the last of the old forests for one more quarter of profit?” I asked. “Or the people who finally said: enough. We will do this differently.”

“I’m not saying we end logging,” I said. “I’m saying we log smarter. Slower. With limits. We can protect core old‑growth and still have jobs. Or we can keep doing what we’re doing and guarantee neither.”

I stepped back.

“Whatever you decide,” I said, “decide like it matters. Because it does. Everything matters.”

The final result was a compromise. Limited logging in some areas, strict protections for the most sensitive sections, increased oversight. Not perfect. But different. Better.

Afterward, people from both “sides” found me. Some thanked me. Some argued. But more important than who agreed or disagreed was this:

People were talking to each other who previously only shouted.

Michael ran up after.

“My dad says you’re crazy,” he said. “But, like, the good kind of crazy.”

I laughed for the first time in a long time.

“I’ll take that,” I said.

XI. One Year Later

Exactly one year after that cold November morning, I stood by Observer’s cairn again. The stones were softened by moss. The carved pendant lay where Sarah had left it, weathered but intact.

“It’s been a year,” I said. “Thought you’d want an update.”

I told Observer about the scout program, now drawing kids from multiple towns. About Michael, applying to study wildlife biology. About Margaret, whose library had become an unofficial environmental education center. About Dale’s coalition of loggers pushing for sustainable practices and finding unexpected allies.

About how the logging proposal near Observer’s old territory had been scaled back. About how the legal battles were ongoing. About how nothing was fixed, but fewer people were pretending nothing was wrong.

“I’m not hiding anymore,” I said softly. “I’m not just a ghost in the woods. I’m part of something.”

I ran my fingertips over the cold stone.

“You were right about us,” I said. “We’re young. We’re foolish. We’re afraid. But we’re capable of greatness.”

I thought of kids asking hard questions, parents rethinking old assumptions, tired activists finding renewed strength in a stranger’s story about a dying forest giant who believed we could still change.

“These seeds,” I said, “the ones you asked me to plant—they’re growing. Not everywhere. Not fast enough. But they’re growing.”

I took a deep breath.

“I can’t promise we’ll fix it,” I said. “I can’t promise we’ll turn in time. But I can promise this: I’ll keep planting. I’ll keep telling your story. I’ll keep fighting for the seventh generation, for the forests, for what’s left.”

The sun broke through the canopy, painting the cairn in gold. For a moment, the world was still.

There was no neat ending. No certainty. No guarantee that all this effort would be enough.

But there was this:

A broken man, no longer hiding, standing in a patch of forest saved—for now—by a web of people who had decided to do their part.

Observer had asked if humans could change.

After a year, I finally had an answer.

Some of us can.

Some of us will.

And maybe, just maybe, that will be enough.

Because in the end, as a dying voice in a cold cave told me and made me promise to remember:

Everything matters.

Everything.

News

9 Hunters Vanished In The Appalachians In 1902 — Their Rifles Were Found Still Loaded

9 Hunters Vanished In The Appalachians In 1902 — Their Rifles Were Found Still Loaded They Follow the Sound A…

LOL!, WATCH Eli Crane BRUTALLY DESTROY Democrat Governor Tim Walz By Using His Own Words!!.

“Why Are You Lying to This Committee?” Eli Crane BRUTALLY Wrecks Gov. Tim Walz With His Own Words Some hearings…

Jasmine Crockett Has a Look of Horror as Host Reads Her Racist Quotes to Her Face

“Do They All Have [email protected] Mentality?” Jasmine Crockett Freezes as Her Own Words Are Read Back to Her Every politician…

Pam Bondi SHUT DOWN in BRUTAL Smackdown Over DOJ Lies, Cover-Ups, and Trump Interference

“I Have 10 Minutes”: Pam Bondi’s Brutal Smackdown Over DOJ Lies, Cover‑Ups, and Trump Interference What began as a routine…

When Tom Cruise Walked Off The View: The Morning TV Meltdown That Broke the Internet

When Tom Cruise Walked Off The View: The Morning TV Meltdown That Broke the Internet Before anyone heard a raised voice…

“Not All Cultures Are Equal”: Republican Stuns CNN Panel With Blunt Defense of Border Security and Critique of Ilhan Omar

“Not All Cultures Are Equal”: Republican Stuns CNN Panel With Blunt Defense of Border Security and Critique of Ilhan Omar…

End of content

No more pages to load