Neighbors Saw Lights Turning On Behind the Wall — Police Were Alerted

At 10:32 p.m. on February 9th, the street was soft with winter quiet—wet leaves clung flat to the curb, and cold air gathered without a wind to push it on. Maple Ridge Drive did not set out to be mysterious. It was a tidy strip of mirror-image townhouses with identical footprints and repeated habits: a porch light at 6 p.m., trash bins at 7 p.m., a garage door rolling down at 9 p.m., followed by the kind of stillness that suggested the day had done its duty. The brick walls were red and evenly mortared, and everything felt like a grid one could map against the palm—predictable lines, right angles, order.

Graham Foster had lived at 1849 Maple Ridge Drive for twelve years. He was fifty-eight now, retired from the kind of engineering that put him inside loud buildings with machines that demanded attention. He missed the noise in a way that he pretended he didn’t. He told people he enjoyed the quiet. Sometimes he did. Sometimes the quiet made him think of how a little pressure—like the weight of a train or a river behind a dam—held structures together. The stillness of Maple Ridge Drive was a lake without ripples.

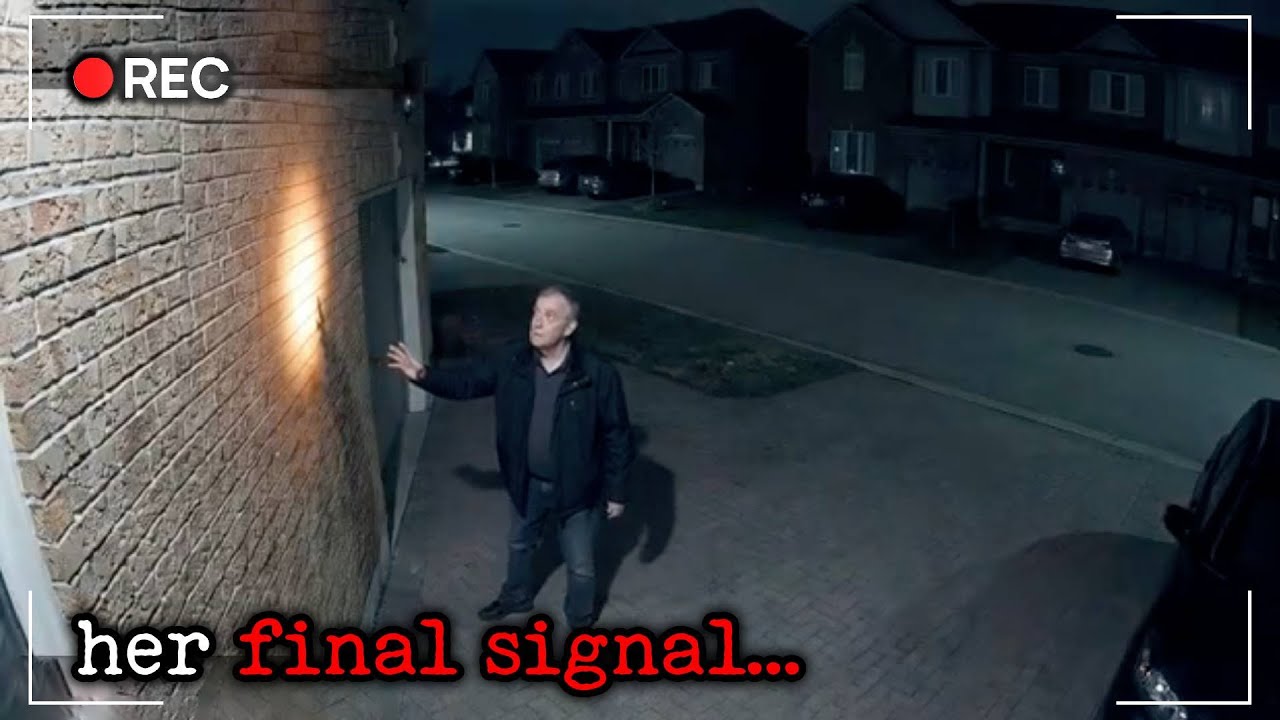

He was standing in his driveway when he saw it. He had stepped out into the night in stocking feet to breathe air he’d convinced himself would help with a persistent headache. He rubbed his temple and looked down the line of townhouses the way he often did—inventorying light fixtures, counting parked cars, mentally measuring distances as if there were some calibration to test—and his eyes brushed past the shared brick wall between his unit and his neighbor’s. And then he paused, squinted, and did not move for several beats.

There was a glow coming from behind the brick wall of 1847 Maple Ridge Drive.

Not inside the townhouse. Not through a window reflecting a lamp. Not a wandering bounce of headlights from the street beyond. It was behind the exterior brick wall—behind, like the word was a place one could go, like it had a depth, like there was space there, like something unseen had been lit.

It was faint. It flickered. It looked a little like the bobbing of a flashlight through a vent, except there was no vent. The glow pulsed, dimmed, brightened, moved sideways as if by inches.

Graham felt the crisp of cold on the backs of his hands. He also felt that sudden, blooded alert that warms a person quickly, the one that reminds you of your own animalness—how quickly a mind can slip from comfort to new appraisal of safety. He stared. He raised his eyes, scanning along the brick, hunting for the source, for a principle of reflection. Maybe the streetlight across the way, maybe—maybe the little world found a trick of angles that made light look trapped where it wasn’t.

But it moved. It dimmed and brightened, again. He swallowed and finished the thought he didn’t like: Someone was in there.

“Impossible,” he said softly to himself, and that word hovered about him like a breath cloud that didn’t dissipate.

Twelve years in the townhouse meant knowledge in his fingers. He could draw the floor plan from memory. Bedrooms upstairs, living room and kitchen downstairs. The garage sat on the first level and was attached; his own garage walls made ordinary thuds when he knocked them. The brick exterior was a veneer over wood framing, insulation stuffed in the cavities, interior drywall. No void wide enough to hold a person. No deliberate space. No hidden room. Maple Ridge Drive had been built in 1998, a development sold on the idea that repetition meant security, and security meant value.

He had seen a flicker three nights ago, too—a small thing go across the mortar line. He had ruled it an angle trick then. Tonight, he felt the ground change beneath that certainty.

Victor Lang lived at 1847. Middle-aged, mid-forties. He wore a day’s growth of beard most days and drove a silver sedan that looked ten years old but clean. He worked, on and off, as an independent contractor—construction, home repairs, landscaping—quiet jobs paid in cash, often done for people who preferred dealing with one person rather than a company. Graham had exchanged niceties with him: snow removal, where the property line technically ran in the back yard, small talk avoided by mutual preference. Lang was a reserved man, not unkind, not unfriendly—he seemed to occupy a lane and hold it.

Graham stood watching for too long, perhaps. He felt a little foolish, like a person who had stared at a cloud waiting for it to become a face. And yet he couldn’t leave it alone. He stepped across his driveway and walked to Lang’s door. He knocked. The sound was mild, and it absorbed itself against the morning-late quiet. He knocked again, a little louder. No answer. Lang’s car was in the driveway. The interior lights of the townhouse were dark.

Graham returned to his own home. He went upstairs, to the bedroom window that faced the shared wall. He turned off his lamp, stepped into the dark, parted the curtain with two fingers, and watched.

Twenty minutes. He could measure that, too. He’d learned the sense of a minute during a lifetime of calibrations—you held it in your mind like a breath you didn’t let go. At nineteen minutes and whatever seconds, the glow returned.

It slipped into being, faint and quick, behind the brick. Something moved, the light bobbed like someone had changed grip on the flashlight.

Graham’s mouth went dry. His hand felt for the edge of his bureau. He held himself steady with one palm on wood knowing he would dial. At 11:04, he called the police.

Officers Denise Holloway and Mark Trinidad arrived at 11:29. Their cruiser’s presence was an official hinge opening on the quiet, a little wedge in the night that made the world perform a different role. Graham met them outside, wearing a parka zipped to his chin and the wrong shoes for the cold. He pointed at the section of wall. They looked, and they saw nothing unusual—brick sealed against winter, red and even. No windows on that side, no vents, no visible openings. Holloway—a woman with a compact build and careful eyes—knocked on Victor Lang’s door. She waited. Knocked again. Announced. No answer.

Trinidad walked the perimeter. He shined his flashlight along the foundation where the brick met poured concrete, where mortar seams gave away lines to water, where small cracks were most often normal. He saw nothing. The brick exterior appeared intact. No gaps. No door disguised as panel. No hook of light catching edges. He returned to Holloway, who had begun to sketch questions out of habit. Had Graham been drinking? No, Graham said, and he found himself bristling at the idea that any deviation from the expected would be treated as an error rather than a signal.

Trinidad called dispatch. They ran Victor Lang’s information. No criminal record. No outstanding warrants. Property taxes current. A file that felt like paper—flat, unremarkable.

Holloway knocked again, louder now, and pitched her voice with authority. “Police,” she said. “Welfare check.” She explained that without response, with concerns raised, they might have cause to enter. A minute pulled itself thin. Then the door opened.

Victor Lang stood there barefoot in jeans and a t-shirt, hair disheveled, eyes not quite alert in the way that people’s eyes are when pulled from sleep. He asked what the problem was, and Holloway explained the report: unusual lights, repeated observations, concern for safety. Lang stared at Holloway like she had told him his car had moved itself. He said he didn’t know what she meant; his lights were off; he had been sleeping. Trinidad asked if anyone else was in the home. Lang said no. He lived alone.

“Can we come in and take a look around?” Holloway asked.

Lang hesitated, and Graham watched the hesitation turn something in his face—a calculation, a reversion to the clear right of an American home. “I’d prefer you didn’t,” he said. “I have a right to privacy.”

Holloway nodded. She agreed, and said she could not force a search without probable cause or a warrant. She gave Lang her card and told him to call if he noticed anything unusual himself. Lang nodded and closed the door.

The officers circled back to Graham. They explained what he already knew and perhaps needed to hear anyway: their limitations were built into law. Call if you see it again, they said. We will respond.

Graham stayed up until after two, but the glow did not return.

On February 11th, it did. At 1:47 a.m., it moved like a fish behind glass—there and gone, then there again, sliding along the mortar. Graham dialed, fresh words on his tongue, his own caution curdled into certainty. Different officers arrived this time. They knocked. Lang answered, and he was annoyed, the muscle along his jaw tense, the margin of his courtesy drawn narrow. He denied knowledge; he said he was tired of being bothered. They left.

On February 13th, the light appeared twice—once at 11:18 p.m., once at 2:34 a.m. Graham called both times. Police responded both times. Lang answered both times. He threatened to file a harassment complaint.

On February 15th, Graham did what the modern world suggests when it doubts you: he recorded video. It was shaky—he was a man standing in the dark trying to hold his phone steady and his breath quiet. But the footage showed the light: faint, moving behind the brick wall. The timestamp was visible. 10:52 p.m. It was enough. Not enough for a conviction, not enough for worse than suspicion, but enough to push a door half an inch farther open.

Detective Bethany Cross was assigned to review the case. She watched the video in a room that smelled like coffee and printed paper, the kind of room where everyone’s attention seems to turn to the same small window of light. She interviewed Graham, took notes in a hand that another detective would later call “really particular,” and read through the previous reports with a patient eye. She had done this work long enough to know the way that some uneventful files hid sharp edges.

She got the building plans for Maple Ridge Drive. The plans were the kind of blueprint that lined up with the developer’s promise: brick veneer over wood framing, insulation, interior drywall. The dimensions were ordinary: no extra space, no structural void large enough to hide even a child. She knew, too, that plans were often the hope rather than the reality; modifications vanished into walls, renovations had their own logic, and sometimes logic itself seemed a nail hammered into wrong places.

On February 17th, she obtained a warrant to search 1847. It cited repeated reports of unusual activity, video evidence, and concerns about building code violations or concealed criminal activity. A judge signed it, and at 7:42 a.m., officers executed the warrant. Lang was home. He stood with his bare feet on concrete and a scowl that looked like a bruise while they served him papers. Then he stepped outside and waited on a sidewalk that had not chosen this morning for drama, and the interior of his life opened for examination.

Inside, everything looked normal. Cross walked through a living room furnished with a couch and a television that offered nothing to look at in itself. The kitchen was clean, the counters wiped, the sink empty. Upstairs, Lang’s bedroom was tidy. The second bedroom was a kind of thoughtless storage—boxes stacked, labels crooked, nothing of note except the way many lives look if you peek at their shelves: the accumulation of things that stopped being relevant without going bad.

Detective Cross knocked on walls—a habit of an old-school detective, maybe, or an engineer’s daughter who had learned sound mattered. She measured. She compared measurements to the plans. The numbers matched in the way they often did when the story wasn’t in the numbers yet. She stressed the corners with her palms and listened.

She went into the garage. The garage is where the private version of a house often reveals itself. There were tools, paint cans, construction materials—enough clutter to belong to a man who worked with his hands, enough order to belong to one who did not wish to live as a stereotype of mess. The back wall faced Graham Foster’s property. It was lined with metal shelving units, the kind sold stacked in a big box store with bright lights and just enough hope that organization might be bought for twenty dollars.

“Move them,” Cross said, and the officers obliged. Behind metal shelves, there was drywall—fresh drywall with seams visible, compound not sanded smooth, a hastiness that takes shape when someone intends to cover rather than finish. Cross knocked. It sounded hollow beyond hollow—like someone had cut away more than the expected. She drew a utility knife and cut through. Drywall parted. Behind the figure of a wall was plywood. Behind plywood was a narrow opening.

Two feet wide, perhaps just less. Cross shined her flashlight into the opening and saw not the edge of a space, but the nervous promise of a passageway. It extended upward, between the brick exterior and the interior wall. The wall cavity had been carved outward—framing cut, insulation removed. The space was built like a reluctant lung. A crude ladder made of 2x4s had been nailed into the framing—stubs notched, rough rungs where hands had learned an exact pattern.

Cross called for additional officers. She radioed for fire department support. She took one breath, remembering the ways this could be dangerous—structural compromise, air quality, the simple fear of unknown design—and then she squeezed through the opening and climbed the ladder.

It smelled like wood dust and metallic edges, like a crawl space where someone had forgotten that memory is an odor. The passageway led to a small space on the second floor, approximately four feet wide, eight feet long, six feet tall. It existed the way secrets do—constructed out of negative space, shaped like a thought a person had put too much time into not showing. Insulation had been stuffed aside. Framing had been cut away, shoulder width stolen from the logic of support. There was a section of the brick interior chipped to create a narrow horizontal opening—an invisible slit from outside: barely six inches tall, running along a mortar line like a dark mouth only a person inside could see from.

Inside the space was a sleeping bag, a battery-powered lantern, bottles of water, granola bar wrappers, a bucket. And photographs. Dozens taped to framing: a woman jogging, getting into her car, walking her dog, sitting on her porch. Telephoto lens distances, crisp enough to identify make and model of car, tight enough to feel close even when far. Cross felt her chest change shape inside her. She knew the woman’s face.

The woman lived across the street at 1852 Maple Ridge Drive. Her name was Kirsten Sawyer. She was in her mid-thirties. Cross had watched her once or twice when filing reports in her car, or maybe she had seen her in the grocery store. She felt that typical memory shift, the way a person becomes a neighbor before they become a victim, and then that word sits waiting, heavy.

At 9:15 a.m., Cross knocked on Kirsten Sawyer’s door. Inside, there was the smell of mint toothpaste and old coffee. Kirsten was getting ready for work. She was a dental hygienist, and she wore the kind of ready posture of people who help others endure small pains professionally. Cross identified herself and asked if they could speak inside. The two women sat in a living room with clean lines—the kind of place that pressed a calm into the air as a chosen habit rather than a natural result.

“Do you know Victor Lang?” Cross asked.

Kirsten said she knew who he was. They had waved politely. They had not spoken. Cross asked if she had noticed anything unusual lately. Kirsten said no, then looked back at Cross’s face and asked why.

Cross explained what had been found: the hidden space, the photographs. She saw Kiersten’s skin pull away from blood, saw the color change to a kind of old paper. Cross showed her some of the photographs, and Kirsten identified herself in each one. She recognized the places—her morning jog route, the grocery store parking lot, her backyard. Some photos had been taken through her windows. The language of intrusion buckled briefly in the room.

Kirsten began to shake. She said she’d felt something recently, like the kind of feeling people get when the shape of a street changes when they walk it at night—like she was being watched. She had thought she was being paranoid.

Victor Lang had been watching her for months. The space inside his wall gave him a direct view of her home. The narrow horizontal opening laced across the brick line gave him a vantage point concealed by the logic of exterior design. He’d used that space to watch without detection, documenting her daily routines, workplace habits, the time her dog liked the porch, the time her bare feet found the kitchen tile.

The glow Graham had seen was Lang’s battery-powered lantern when he moved through the passageway to reach the observation slit. Cross thought of the way life felt safe until it did not, how trust in construction was a kind of faith in behavior, and how quickly one person’s obsession can make architecture complicit.

Lang was arrested and charged with stalking, criminal trespass, and voyeurism. A search of his computer revealed additional photos and videos of Kirsten—some dated more than a year before. The record had the sick order of logs: timestamp after timestamp, route after route. He had made a language of her life and studied it.

At trial, Lang’s defense argued that he had never physically approached or threatened Kirsten. He had watched, they said, in the way that the world watches: cameras on every corner, phone lenses everywhere, screens saved like hearts. Cross listened to how language was used to bend fear into less than what it was. The prosecution argued that obsession had a curve, and it often steepened. They argued that the behavior demonstrated a credible threat, that surveillance is not neutral when it serves the desire of one over the safety of another. Expert witnesses testified about stalking patterns and the escalation that often ended in violence. A jury took a day and a half and returned with a clear judgment: guilty on all counts.

Lang was sentenced to twelve years in prison. Cross did not feel relief exactly; she felt a seam tighten where it had loosened, felt cold air being buttoned out of a room. That night she slept a little better, then woke at 3:00 a.m. and did not return to sleep, because some nights demand you think about every unspoken story, every retreated footstep, every window that is not a slit.

Kirsten installed security cameras around her property. She changed her routines. She moved six months later because her body could not unlearn a place where she had been watched without knowing it. She left behind a porch that fit her and a kitchen where her coffee had its seat, and she learned a new house’s quiet the way one teaches a dog a new name.

Maple Ridge Drive went on. The townhouse at 1847 was sold. The new owners hired a contractor who sealed the hidden passageway and properly insulated the wall cavity. The property was inspected and brought up to code, which is what the world calls it when its best practice meets its intention.

Most nights did what they had done before: they flattened into stillness after 9 p.m. The streetlights wore their halos, and the brick caught those halos and did not seem like it could ever convert them into anything else again.

Graham Foster’s decision to report the lights—and his refusal to treat dismissal as conclusion—had led to a discovery that turned a narrative of safety into a series of questions. He did what people tend not to do: he believed his senses over a polite certainty in the structure around him. He stood at a window until his body insisted on a raised word. And because he did that, a person across the street was protected before someone else escalated further. The world bent a little, but not into something it could not return from.

After the trial, after the relocation, after the inspection, after the street settled back into its old rhythm, Detective Cross went to see Graham. It was summer now. He was out front, home from a morning’s errand to the hardware store, cutting back a hedge that had found a quicker spring than the year before.

“Mr. Foster,” she said. “I wanted to say thank you.”

Graham lifted his head slowly. “You’re welcome,” he said, and that seemed to be all. He paused, then said, “I don’t know that thank you is what you should say. I’m just glad someone listened.”

Cross nodded. She wanted to measure words against the edge of misbehavior, but this was not a day for that. “You did right,” she said. “Most people talk themselves out of calling. You didn’t. That matters.”

He looked at her with a small calculation in his eyes. “It was a light,” he said, and he thought of the way his own mind had treated it like an artifact of angle at first. “It was just a light.”

Cross said, “The world’s full of little things that aren’t just little,” and left him with his hedge and his morning, the quiet already settling into the view like a blanket.

At first, the neighborhood handled the story by layering commentary that felt safe: legally where do the liabilities land? Did the HOA know? Did the builder cut corners in 1998? Did Victor Lang show signs? Was he always the kind of quiet that seemed not like solitude but like hiding? But quickly, the talk turned toward what people were unwilling to ask aloud: how proximate danger can be to us, how little we understand the structures we live inside, and how our bodies stitch trust into spaces without knowing the knots might slip.

A month after the trial, a new tenant moved into 1847. Her name was Renee, a nurse at the hospital on the other side of town. She had short hair and a laugh that arrived quickly and stayed. She had read the disclosure with a curious steadiness—a person who faced emergency rooms without losing her hands—and signed anyway. She walked the garage’s back wall with her palm flat against fresh drywall and felt nothing except a reminder of how much homes ask of the people who live in them: that they sleep without too much fear, that they trust without too many contingencies.

The passageway now sealed was a story inside her new home more than it was a place. She imagined what the hidden space had looked like and then reassured herself by not imagining too much. In the months after she moved in, she waved to Graham, learned the name of the dog that lived across the street, and watered a hanging fern. There is an argument to be made that ordinary acts restore ordinary places more completely than victory does—watering a plant as a form of defiance, washing dishes as a form of reclamation.

Holloway and Trinidad kept the case in their minds longer than they admitted. Holloway began to think about the shape of warrants, whether judges are supposed to be better at guessing what the world’s strange corners hide. Trinidad bought a book about building code not because he wanted to be an inspector but because he wanted to learn how houses bend to other people’s desires.

Cross put the photographs in evidence and visited them twice, pulling a form out and a folder out so that her eyes could remember details that her brain would otherwise flatten into narrative. She noticed the way the telephoto lens had made the world look like it was always about one person. She noticed the way windows made the world poems for some eyes and prey for others.

One day in late August, Cross sat alone in her small office with a sandwich and the receipt for the sandwich and read about stalking patterns again. She had a highlighted paragraph she had circled three times: victims often report senses of being watched without proof, and their accounts are frequently discounted as anxiety or misinterpretation. She pressed the paragraph down with the length of her finger and felt anger draw a seam in her hand. She thought about all the ways the world dismisses edges. She thought about how nothing is more dangerous than being right when every structure says you’re wrong.

She wrote to the department about a small idea: an internal reminder to take repeated gut-level reports more seriously. She did not call it that, precisely. She wrote numbers and frequency and a draft of response protocols. She did the work inside the language of institutions—it was the only way to move water through pipe.

And Maple Ridge Drive remained Maple Ridge Drive. Saturdays held back the sound of children’s bikes. Built into the quiet was a new awareness—the sense that behind surfaces we assented to, there were shapes we might prefer to disbelieve. But that sense didn’t crush ordinary life like an overpacked suitcase. It sat adjacent, like a second view of the same scene: one primary, one cautionary.

Months later, on a late-autumn evening when a thin rain did not decide whether it wanted to be rain at all, Graham stood in his driveway again. He watched light slip against brick, but this time it was the usual trick of the streetlamp against damp mortar, the kind of shifting that had moved into his world as acceptable again. He held a small bag of nails, bought because he liked the familiarity of their cold weight in his palm, and thought about being noticed. By whom, by what. The light behind the wall had used noticing in a way that had saved someone. He exhaled and let that be enough for a moment.

He remembered the first time he had walked through 1849 with the realtor. The woman had said words about square footage and resale value and layout. He had measured with his eyes. He had mapped. He had stood in the garage and knocked on walls because he liked knowing how things sounded. He had said, “This feels sturdy,” and the realtor had smiled. He did not think she had known what sturdy meant to him—an exactness, a certainty in numbers—but perhaps she had known what sturdy meant to people with mortgages: you sleep comfortably.

He laughed at himself then and went back inside.

The light that had flickered behind the wall on Maple Ridge Drive was not paranormal. It was not a reflection. It was the evidence of a predator watching his target from a space he had built in defiance of both law and the social agreements that allow neighborhoods to be neighborhoods. A man had made an opening in brick because he wanted to see someone in a way she had not permitted. A neighbor had noticed something out of place and had refused the impulse to call himself silly. A detective had used permission to look at what was arranged to be hidden. The whole structure of safety had been tested, and it did not fail.

But it had curbed. It had bent. It had reminded everyone that structure, like trust, can be altered by one person’s fingers if no one else’s eyes are on it. And then it had reminded everyone that eyes matter, too: an old man’s eyesight, a detective’s flashlight, a jury’s collective assessment.

In the months after, Graham began to walk more often at night. He did not do this because he wanted to be a detective or because he wanted to prove a point. He did it because he liked the quiet again, and because his body had learned he could walk amid the uncertain and survive it. He watched the pattern of windows: the TV glow moving across walls, the lamplight doing what it always had done, the porch light going off at 9:55 like clockwork. He watched for deviations, and when he saw them, he measured his fear and then went inside and went to bed.

One evening, he saw Renee on her nice porch. She had a book and a blanket. She lifted her eyes and waved, and he said, “How are you settling in?”

“Good,” she said, and she meant it. “It’s quiet.”

He nodded. “It usually is.”

They were about to retreat to their own quiet when she said, “I know what happened here.”

He stopped, then said, “Ah.”

“I don’t mind knowing,” she said lightly. “I prefer knowing to not knowing. If something is in a wall, I want it outside the wall. Or at least sealed and named.”

“Named,” Graham said, and the word felt right.

She asked him, “What did you think when you saw the light?”

He thought for a second, then said, “Honestly? I thought I might be wrong.”

“And then?”

“And then I didn’t care. I called.”

She smiled. “Good,” she said. “It’s funny how often we wait for something to be big before we tell anyone. As if small things aren’t sometimes the only evidence we’ll ever get.”

He nodded. They shared the kind of silence that suggests a conversation is complete because it has reached the natural end rather than because it has run out of energy. He went inside and made tea, which tasted like a new habit even though he had been brewing the same leaves for years.

In early winter, Cross returned to Maple Ridge Drive to visit the scene again. Not for evidence; not for a new report. She walked the perimeter of 1847 and 1849 like a ritual. She kept her hands in her jacket pockets and her eyes practiced. She examined the mortar line where a slit had been chipped from the interior, a line so ordinary that its previous use now felt implausible. She also thought about how eyes cause plausibility to shift faster than law.

She knocked on Graham’s door. He answered with the composure of someone who no longer expected trouble when a knock arrived. She asked, “How are you?”

“I’m fine.”

“How’s the street?”

“The street is a street,” he said. “It does the things streets do: stays still, holds cars, offers frontage to people’s days.”

They smiled. She said, “I sometimes wonder if stories like this are where neighborhoods find their seams. Everyone knows the same thing happened, and then they go back to their private versions of common ground.”

“Sometimes,” he said. “But sometimes stories like this make people wave to each other more. Sometimes it makes them look up. That’s not a seam; that’s a stitch.”

He had not been an engineer of textiles, but he had an engineer’s appreciation for analogies that used materials. She left him at his door and walked back to her car, thinking about words like seam and stitch, thinking about how the world’s safety is a fabric rather than a wall: woven, layered, mended.

Kirsten came back to visit once. She walked Maple Ridge Drive with a friend, and she did not cross the street to stand outside her old home because she did not need to. She was not performing closure for anyone who might imagine it. She let the quiet be a quiet she did not belong to anymore. She remembered the photographs and then she let them burn without fire in the part of her mind where decisions get made for you by time. She lived in a new place with cameras and routines that did not match previous routines. She learned that safety is not a guarantee; it is a practice. She learned to trust herself more—her instincts, her gaze—and to build trust up in layers like bricks sealed with good mortar.

On the night it all began—the first flicker—Graham had leaned on his bureau with a palm and watched. He had felt stupidity and fear both go through the same small gate and emerge as action. Months later, when he told the story to a new friend over coffee, the friend asked, “What was the turning point?” and Graham said, “I think the turning point is always smaller than it looks. It’s the distance between a breath and a dial.”

The friend laughed and called that line good. Graham did not think he was good at lines, but he accepted the compliment and changed the subject. He had lived a life in the space between a measure and a fix, and that meant he knew the daily weight of small adjustments. He did not expect anyone else to admire those the way he did, but that was fine. He knew their value.

The brick wall on Maple Ridge Drive had held a light inside it briefly, and it had offered that light up to a person who would notice. The wall itself did not care about the story, nor do walls care. But the people did. And that’s the part we call a neighborhood: not the uniformity of layout, but the shared regard for the small details that add up to security.

In winter, a woman left a pie on Graham’s porch with a note that said, “Thank you for watching.” She signed only as “A neighbor,” but he suspected it was the woman with the young dog who had started walking at different times of day after the whole thing happened. He did not call the number she had left below the signature; he simply wrote a thank-you note in return and slid it under her mat. There are ways of living together that require no shared calendar.

In spring, High Schoolers chalked hearts on the sidewalk. The hearts washed away in rain and reappeared in new colors, and the cycle felt like the only cycle anyone should argue for. People left, people came. The inspection papers on 1847 were folded into the drawer that took warranties and receipts and maps.

The headline that had once been printed looked like all small-city headlines: “Hidden Wall Space Used to Stalk Neighbor,” and it had a photo of the exterior that gave no information and did not need to. It was cut out and saved by five people who guessed they would want to frame memory later. It was discarded by dozens who wanted to reduce the story’s diet to zero.

Years went by. It was still Maple Ridge Drive. Children grew up and left behind scooter scuffs on the lower brick that would make somebody laugh after a move-out day. Renee married and sold the townhouse to another pair of hands that would seal this version of themselves inside these rooms for a while. Graham got older and walked slower and learned to regard his body as evidence of time rather than as a failure. Cross was promoted. She carried the case number in her mind as a kind of footnote beneath other case numbers.

If you asked what changed, the answer would look like this: people believed themselves a little more when their senses insisted. People called sooner sometimes. And when they did, they used the quiet of their neighborhoods as a measure rather than as a pressure to maintain the moment’s decorum. They knocked, they answered. They regarded. That is not a grand story in the way movies want. It is a small story in the way life requires.

On the anniversary of the day the warrant was executed, Cross drove past, then parked. She sat with the engine off. She watched the brick wall of 1847 and the window of 1849 and the porch of 1852 where someone else now sat with tea. She thought about the idea of behind, how wide that word can be, how we live next to each other’s behinds and know nothing of them, how secrets make of architecture a second language, how noticing translates.

She thought about the light: how it was a relay baton passed from predator to neighbor to detective to jury to the shifting set of citizens who might someday have to trust somebody else’s eyes. The baton did not glow anymore, but the relay had happened, and the course had been rounded.

The world is full of little flickers, and most of them mean nothing. But some mean everything. Maple Ridge Drive learned to treat the next flicker with humility and with regard. It did not become paranoid. It became attentive. Safety lived in that distinction.

That is the story of the light behind the wall. It is a story of brick and habit, of obsession and restraint, of the space between the obvious and the true. It is a story about how the quiet of a street can cover a predation and how that quiet can produce the kind of neighbor who will not let a flicker be dismissed as an optical error.

Because one person refused to dismiss what he saw, another person was protected before harm escalated. Because a detective moved into negative space, the positive space of safety held. Because a jury was asked to read a pattern, the pattern did not write its own ending. And because the light was recognized as not a trick but a warning, the story that might have been written in secret became a public document, and then it became memory, and then it became practice.

It is not a story with a twist except the one where a wall gives way to a passage. It is not a story with a chase except the one where the body runs in the mind. It is not a story with heroism except the one where a man calls. And it is not a story with a villain except the one where obsession refuses to be contained in ordinary forms.

It is a story about place. And it ends where it began: with a quiet street, a grid, and a person standing in a driveway who will notice the next flicker and call again. If you need it to be more than that, you do not understand what safety asks of us. If you need it to be less, you do not understand how quickly stories like this become history if they are not caught.

What happened was simple and not simple. A light behind a wall. A call. A search. A hidden space. Photographs. A charge. A trial. A sentence. A move. A sealing. A return to quiet with a new layer of attention. The brick line is repaired. The mortar is sound. The neighborhood proceeds. It carries the weight of knowledge like all neighborhoods do—quietly, thoroughly, sometimes forgetting until reminded, and then remembering in time.

The glow is gone.

The attention is not.

News

Samuel L. Jackson Kicked Off Good Morning America After Heated Confrontation With Michael Strahan

Samuel L. Jackson Kicked Off Good Morning America After Heated Confrontation With Michael Strahan Live television is unpredictable. It’s the…

Billy Bob Thornton Kicked Off The View After Fiery Argument with Joy Behar

Billy Bob Thornton Kicked Off The View After Fiery Argument with Joy Behar Television talk shows thrive on tension. They…

Danny DeVito SNAPS on Live TV Over Mental Health Debate – You Won’t Believe What Happened!

Danny DeVito SNAPS on Live TV Over Mental Health Debate – You Won’t Believe What Happened! In a media landscape…

Bill Maher & Tim Allen EXPOSE Media’s Anti Trump Bias on Live TV

Bill Maher & Tim Allen EXPOSE Media’s Anti Trump Bias on Live TV For nearly a decade, the dominant image…

Jack Nicholson EXPLODES on The View — One Question From Joy Behar Triggers a Live TV Meltdown

Jack Nicholson EXPLODES on The View — One Question From Joy Behar Triggers a Live TV Meltdown Every medium has…

When Their Dating App Scheme Turned Deadly

When Their Dating App Scheme Turned Deadly Just before dawn on May 17th, 2024, Fifth Avenue North in Minneapolis looked…

End of content

No more pages to load