“They’re erased, they’re coming after us”: Digital erasure and anxiety after the Charlie Kirk shooting video wave

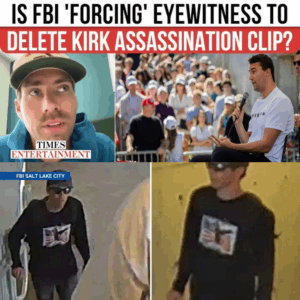

In the hours and days following the fatal shooting of conservative activist Charlie Kirk at a campus event, a wave of social-media clips, phone-recorded videos and eyewitness uploads flooded the internet. At the same time, a number of people who say they captured or saved footage of the incident report sudden disappearances: videos “gone from my phone,” posts removed from accounts, unexplained erasures, and a feeling of being silenced.

“I literally will stay here … So all of you … like I’m not, I don’t care. Everyone can see. … Best that you erase the video from your phone because it’s just going to give you PTSD … and then call it another time to ask if I erased it.” These words, drawn from a user’s post, capture a mixture of anxiety and suspicion: of how digital evidence behaves, how platforms respond, and what happens when ordinary people become custodians of raw footage.

This article explores three threads: what is happening with the videos and social media platforms; what the disappearance or removal of footage means for public record and trust; and what the broader implications are for media, trauma, and the politics of digital suppression.

The Surge of Footage – and the Removal

Within minutes of the shooting, cellphone video clips of the incident began circulating widely. According to coverage in WIRED, social-media platforms were flooded with multiple angles of the moment Kirk was struck, some showing him collapsing, others showing the rooftop vantage point of the suspected shooter. The scale of sharing was enormous and rapid.

At the same time, platforms such as TikTok announced that they would remove videos showing the shooting or flag graphic content. For example, the CBS News article reported: “TikTok says it will remove videos that show close-up views of the shooting and remove search terms related to it.” An Associated Press piece added detail: While footage continued to circulate days later, platforms said they would age-restrict or label graphic items but acknowledged the difficulty of full removal.

The rapid spread of graphic content—and the equally rapid purging or concealment—created a strange dynamic: footage is everywhere, and yet many individual recorders say their videos “vanished.” One person wrote publicly:

“Bunch of my videos are gone. Even right to post these videos … that was on my other account that was gone … just was removed. … So originally when I sent this video in to the FBI for tips … I thought I was doing a service … That person had called me back … said ‘because this was your friend … I think it’s best that you erase the video from your phone because it’s just going to give you PTSD.’ … And again, that’s when I started sharing, posting, and saving on many different hard drives … It’s been rough. … My phone turning different colours and feeling like it’s lagging … typing different things … and then later on I woke up today and bunch of my videos are gone … from my library.”

While such claims require verification, they fit into a pattern: the volume of distributed footage is enormous but access at the individual level becomes fragile.

What Is Being Removed—and Why?

Why are videos disappearing? There are multiple possible mechanisms:

Platform moderation and policy enforcement. Many platforms have policies against “graphic violence,” “victim blowback,” “non-consensual images,” etc. The WIRED article noted that though the shooting footage clearly violated company rules, widespread moderation was incomplete.It delved into how algorithmic feeds, autoplay features, and weak moderation allowed graphic violence to spread. The Associated Press story looked at the same issue and asked whether platforms were failing or choosing to leave content up.

Legal, investigatory or law-enforcement pressure. One reason a user says the FBI urged erasure of his phone video was because of PTSD risk. While that may sound benign, it raises questions about what happens when individuals become recorders for investigations. In high-profile incidents, law enforcement may ask for cooperation and may also restrict publication of raw footage until evidence collection is complete. That may lead to videos being taken down or removed from public view.

User account removals or platform self-removal. The person quoted above says their old account “was gone” after five years of posts. That suggests account suspension, removal of content by the platform, or other enforcement actions. The visibility of content, once posted, is never guaranteed.

Digital fragility and archiving failure. Personal phones, cloud backups, hard drives—all can fail, be hacked, corrupted, or subject to deletion (accidentally or intentionally). In crisis moments, panic, overload and poor backup behaviour may lead to perceived “vanishing” of videos. This is especially true when users scramble to save and repost in multiple places.

Whatever the mechanism, the effect is a perceived mismatch: “I captured something, others saw it, but now I can’t access it.” The question becomes less “what was recorded?” and more “who can keep the record?”

Trust, Evidence and the Public Archive

When raw footage of high-profile violence is recorded and circulated, it functions as both news and evidence. The erosion or removal of such footage has multiple consequences:

Erosion of public trust. If ordinary people record something and then find the video removed, they may feel targeted, censored or powerless. Meanwhile, the fact that some videos remain available (or re-uploaded) but not others reinforces perceptions of selective suppression. In politically charged cases—like the Kirk shooting—it can fuel belief in conspiracy, selective enforcement, or hidden motives. Indeed, a fact-check article by NBC Philadelphia noted that “false claims” were spreading after the Kirk shooting.

Challenges to accountability and verification. When footage disappears, verifying exactly what happened becomes harder. Investigators may rely on surveillance, witness statements, phone footage; social-media backups may vanish or be removed. If a recorder deletes a video at the request of authorities (or under pressure), it raises the question of access: who gets to see the full record?

Trauma, archive and memory. Recording violence has dual impact: it can help document, but it also can traumatize those who hold the footage. The user’s quote about PTSD is instructive: someone told him to erase the video from his phone because it would “give you PTSD.” That reflects a tension: collecting evidence vs protecting mental health. If individuals are instructed to destroy their own files, the archive is weakened and public memory becomes dependent on whatever remains.

Platform and algorithmic power in shaping narrative. The fact that algorithms determine what gets seen—and what gets amplified—matters especially when content is being removed, restricted or age-gated. The WIRED article stressed how autoplays and feeds can push violent content even when platforms claim to restrict it. When combined with removals, the visible archive becomes patchy and uneven.

Voices of Concern from Recorders

The quoted individual reflects a few recurring themes:

Loss of personal footage: “Bunch of my videos are gone… from my library.”

Platform removal of accounts/posts: “My other account … was gone and just was removed after 5 years of building it.”

Pressure or suggestion to erase footage: “That person … said ‘erase the video from your phone because it’s just going to give you PTSD.’”

Technical glitches or suspicion of tampering: “My phone turning different colours … feeling like it’s lagging … typing different things that I’m not typing.”

Urgency to back up and distribute: “Screen record them. Spread them. Do everything you can. Literally, they are coming after us.”

These speak to an acceleration of what technology researchers call “participatory witnessing” (ordinary people recording events) combined with “digital fragility” (loss or removal of footage). The emergence of narratives around removal fuels suspicion, regardless of whether removals are accidental, policy-driven, or intentional.

The Broader Cultural/Political Angle

The shooting of Charlie Kirk is not only a criminal case; it is a political flashpoint. The context includes campus free-speech debates, conservative activism, national politics, and media spectacle. In that environment, the presence or absence of raw footage carries extra weight.

Platforms’ moderation decisions have political consequences. Should graphic videos of a public figure being shot remain accessible? If yes, under what constraint (age-gate, warning label)? If no, does removal become a form of editorial control? The Associated Press article asked: was the content being removed due to failure of moderation, or because platforms chose to keep it up?

The fact that a user claims the FBI asked him to erase video adds another layer: investigatory priority vs public transparency. In politically charged events, that tension is magnified.

The sense of “they are coming after us” is more than paranoia—it reflects how many participants in digital media now conceive of their role: recorder, witness, distributor, target. When ordinary users feel their footage may vanish, they may interpret that as suppression—even if the mechanism is benign (account action, storage error, etc.).

What Needs Scrutiny and Policy Attention

Several policy and ethical issues emerge:

Transparency in moderation and removal. Platforms should clarify which videos are removed, which are age-restricted, and provide audit trails. When people say “my videos are gone,” there is no clear public record of why.

Archive integrity and public access. Raw footage of violent public events can serve as evidence. Ensuring multiple independent backups, open-access repositories, or archival norms may help preserve them for investigation and public record.

Protecting citizen-recorders. Those who film such events may face trauma, threats (online or offline), pressure to delete footage or hand it to authorities without guarantee of privacy or access. Protocols for protecting such individuals would strengthen democracy.

Algorithmic amplification and emotional impacts. Autoplaying violent footage may traumatize bystanders. At the same time, algorithmic promotion of such material can distort public perception. The earlier WIRED piece warned of the “psychological damage” of watching raw footage of a person’s death

Political neutrality and editorial fairness. In a polarized environment, decisions about which footage remains, which is removed, and which is age-gated can generate allegations of bias. Clear consistent standards matter.

What This Means for Individuals

If you are someone who records footage of a public violent event—and you hang on to it—you might consider:

Backing up your footage to multiple devices/hard-drives not connected to the internet.

Labeling and time-stamping the files.

Understanding your rights: Are you contacted by law-enforcement? Are you being asked to delete footage? Why?

Watching out for device behaviour: unusual lags, color shifts, typing changes may indicate malware—or may be stress-related. Either way take seriously.

Being aware that once footage is posted publicly, the platform may remove it or repurpose it; you may lose control of how it is used.

Reflecting on the Quote

The user’s quote—“they’re literally coming after us”—is emotionally charged but telling. Even if “they” simply means platform moderators acting under policy, the perception of threat is real. When the act of recording becomes fraught—with account disappearance, footage vanishing, calls from authorities to erase—the recorder’s sense of agency and trust shrinks.

The line “because this was your friend, I think it’s best that you erase the video from your phone because it’s just going to give you PTSD” raises multiple questions: If erasure is for you (the recorder), fine. But if erasure is for them (the interested party, law enforcement, platform), it raises questions about whose narrative is being preserved and whose is being lost.

Final Thoughts

This story is part criminal investigation, part media spectacle, part digital trauma. The shooting of Charlie Kirk and the subsequent visual avalanche came at a moment when nearly everyone has a phone in hand, when social platforms can spread footage in seconds, and when the politics of who sees what—and who keeps what—are acute.

When ordinary people film and then lose that footage, the loss is both personal and civic. It speaks to trust in platforms, law enforcement, public archive, and self. The question becomes not only what happened at the event but what happens to the record of what happened.

If we accept that an open society needs open evidence, then we must ask: How do we preserve witness footage? How do we protect recorders? How do we ensure platforms don’t silently erase or hide content? And how do we safeguard mental and digital health of those who carry the burden of seeing, shooting and sharing?

In the end, the disappearance of videos isn’t just a glitch—it is a signal. A signal that in the digital age, what we see, what we keep, and what we lose are central to truth, justice and trust.

News

When Grief Becomes a Performance? A Conversation About Body Language, Optics, and Public Mourning

When Grief Becomes a Performance? A Conversation About Body Language, Optics, and Public Mourning A few days after Charlie Kirk’s…

Court Orders Civilian Clothes, Restraints for Suspect in Charlie Kirk Case

Court Orders Civilian Clothes, Restraints for Suspect in Charlie Kirk Case A major procedural decision was handed down Monday in…

Why I Chose to Vote Democratic: A Conversation, a Reflection, and What It Says About Our Politics

Why I Chose to Vote Democratic: A Conversation, a Reflection, and What It Says About Our Politics Four days ago,…

Lindy Lee vs. Chuck Schumer: The Viral Political Roast That Shook Washington

Lindy Lee vs. Chuck Schumer: The Viral Political Roast That Shook Washington Introduction: When Politics Meets the Internet Age It…

Greg Gutfeld and Kat Timpf Roast George Conway in Viral Fox News Segment on Political Outrage Culture

Greg Gutfeld and Kat Timpf Roast George Conway in Viral Fox News Segment on Political Outrage Culture New York, NY…

Tyrus Confronts Hillary Clinton On-Air in Explosive Exchange Over Benghazi, Emails, and Political Legacy

Tyrus Confronts Hillary Clinton On-Air in Explosive Exchange Over Benghazi, Emails, and Political Legacy New York, NY — A heated…

End of content

No more pages to load