The Last Friend in the Cascades

How a Widower Spent 25 Years Learning from Bigfoot

I’m 97 years old, and for more than 50 years I’ve carried a secret no one would believe—even if they begged me to prove it.

Between 1973 and 1998, up in the Cascade Mountains of Washington, I met the same Bigfoot at my cabin again and again. Long enough for him to show me things about humanity I wish I didn’t know.

This is the truth I’ve avoided telling my entire life, and why I can’t hold it in anymore.

My name is Earl Whitaker.

In 1973, I was 45 and freshly widowed. Martha had died that spring from breast cancer, and I couldn’t stand being in our house in Bellingham anymore. Everything reminded me of her: the kitchen where she baked bread on Sunday mornings, the porch where we drank coffee and watched the sunrise, even the ugly wallpaper she’d insisted on back in ’68.

So I did what a lot of broken men do.

I ran.

I had a small inheritance from Martha’s family and some savings from my years at the lumber mill. I bought 60 acres of dense forest about forty miles east of Concrete, Washington. A narrow creek cut through the property, and the previous owner had built a small cabin in the 1950s:

one bedroom, a main room with a wood stove, an outhouse, and a hand pump for water. No electricity. No phone.

Perfect.

I moved in July ’73, driving my ’68 Ford F‑100 with everything I owned tied down under a tarp. My supplies were simple: canned food, a kerosene lamp, tools, my hunting rifle, and a transistor radio so I could catch baseball games and the news.

The cabin sat in a small clearing, surrounded by Douglas fir and western hemlock that rose like cathedral pillars. The nearest neighbor was eight miles away.

For the first two months, nothing strange happened. I chopped wood, patched the leaking roof, figured out how to live with the silence. Martha and I had been married 23 years. The quiet felt like a physical weight.

Then came September 17, 1973.

I remember the date because it was a Monday and Howard Cosell had been talking about the Billie Jean King “Battle of the Sexes” match on the radio the night before.

I woke at dawn to a sound I’d never heard before.

A low, guttural moaning from somewhere near the creek—maybe two hundred yards from the cabin.

I grabbed my rifle and went to investigate.

The Creature by the Creek

The morning fog lay thick over the ground, rolling through the trees like smoke. The moaning came in ragged bursts. I followed the sound, boots crunching on wet needles.

At first I thought it was a bear.

It was lying on its side near the creek bank, half hidden by ferns. But as I got within thirty feet, my brain rebelled.

This was no bear.

The thing was enormous, easily seven feet tall even curled on its side, covered in dark reddish‑brown hair. Its shoulders were impossibly broad. One leg was twisted at an angle no joint should ever make.

It saw me and tried to rise. It collapsed with a sound that was almost human.

That’s when I saw its face properly for the first time—and my mind left the world I thought I knew.

It wasn’t quite ape, and it wasn’t quite human. Heavy brow, broad, flat nose, wide mouth, and eyes—deep‑set, dark, and intelligent in a way that froze me to the spot. It wasn’t looking at me like an animal looks at a threat.

It was studying me.

My rifle was already raised, finger on the trigger. It was 1973—no internet, no YouTube channels arguing over blurry footage. I knew of the 1967 Patterson–Gimlin film; I’d seen stills in a magazine. Most folks said it was fake.

Standing there, staring at this thing bleeding onto the moss, I knew Patterson had told the truth.

The creature made a sound, not a growl—more like a question. It lifted one massive hand and gestured weakly toward its injured leg.

Five fingers.

Long, thick fingers that could have snapped my neck like a twig.

I lowered the rifle.

To this day I can’t tell you precisely why. Maybe it was loneliness. Maybe it was those eyes. Maybe it was simply that I’d buried someone I loved that spring and couldn’t watch another living thing suffer if I had any say in it.

I went back to the cabin, grabbed my first‑aid kit and some old towels, and returned.

The creature watched every step.

Up close, its hair was coarse, more like a horse’s mane than fur. The skin beneath was dark gray, almost black. Its lower leg—tibia, I think—was fractured. I had no way to set the bone properly, but I could clean the wound and stabilize it.

For nearly an hour I worked as this seven‑foot being lay perfectly still, allowing a fragile human to touch it.

The hydrogen peroxide fizzed and hissed in the wound. It rumbled deep in its chest, a warning perhaps—but didn’t pull away. I cut two straight branches for a crude splint, bound them tight with rope and strips of towel.

Those dark eyes followed every movement of my hands.

When I finished, I backed away slowly.

The creature pushed itself upright, breathing hard, and examined the splint. Then it looked at me.

It made a sound I can only describe as acknowledgment.

Not gratitude, exactly. Just: I see what you did.

Then it stood, balancing on one leg, grabbed nearby trees for support, and hobbled into the forest.

I didn’t expect to see it again.

Three days later, I found a freshly killed rabbit on my porch. No footprints I could clearly trace, no note tied in twine—just a clean kill, still faintly warm.

I knew.

It was watching.

That’s how it started.

The One I Called August

Over the next two years, a pattern formed.

I began leaving scraps at the edge of the clearing: apple cores, bread, a bit of stew in a dented pan. By morning, they were gone.

Sometimes, something would be left in return:

Trout from the creek

Wild mushrooms, always edible

Once, a deer haunch that kept me fed for two weeks

I didn’t see the creature clearly in those early years—just glimpses. A shape slipping between trees at dusk. A tall shadow crossing the moonlit ridge. The sound of something big moving through underbrush.

But I knew it was there. Watching. Evaluating. Learning me the way I was trying to learn it.

In the spring of 1975, I was splitting wood when I felt that distinct, skin‑prickling sensation of being watched. I turned.

It was standing at the edge of the clearing. In broad daylight.

Maybe sixty feet away.

It was taller than I’d judged by the creek—seven and a half feet, maybe more. The leg I’d splinted two years earlier had healed; it favored the other leg slightly, but it stood firm. The fur on its face and chest had more gray mixed among the reddish brown than I remembered.

We stared at each other for what felt like an hour but was probably two minutes.

Then I did something insane.

I raised my hand and waved.

The creature tilted its head, considering, then raised its own hand and mimicked the motion.

I felt something shift inside my chest.

I started calling it “August” in my head—not because that was its name, but because late summer was when our strange arrangement settled into something more deliberate.

By 1976, we had a rhythm.

Not friendship. Not exactly. But a cautious, mutual understanding.

August appeared every few weeks, mostly at dawn or dusk, always staying at the edge of the clearing. I’d talk aloud sometimes—about the mill, about Martha, about how quiet the cabin could feel at night.

I knew it didn’t understand the words.

But it understood tone. And it understood loneliness.

A Name, and Lessons Without Words

In 1976, I bought a green canvas notebook in town and started writing everything down: dates, times, behavior, the gifts left and received. I still have that notebook—along with eleven more.

Later that year, something happened that changed everything.

I was replacing rotted boards on the front steps. I set my hammer down, turned to measure a plank, turned back—and the hammer was gone.

I looked up.

August stood about thirty feet away, half‑hidden by trees, holding my hammer. It examined the tool with the focused curiosity of a child with a new toy.

I held out my hand, palm up.

August watched me for a moment, then walked closer—closer than ever before—and placed the hammer gently into my hand.

Its palm was rough and calloused, like someone who’d worked heavy labor for decades. The contact was brief, but unmistakably intentional.

We were maybe ten feet apart now.

Up close, I saw more detail: deep brown eyes with flecks of amber, a broad nose, dark lips capable of subtle expression, several old scars across face and muzzle. A lifetime carved into its features.

“Thank you,” I said, out of habit.

August rumbled softly in its chest, touched its own chest with a thick finger, and then pointed at me.

It took me a moment.

“You want to know my name?”

I touched my chest.

“Earl.”

It watched my mouth form the word, but when it tried to copy the sound, nothing remotely similar came out. Instead, it made two short grunts and touched its chest again.

Its name, in its own language—something my throat wasn’t built to say.

“August,” I said quietly. “I’ll call you August.”

It didn’t correct me.

From there, its intelligence became impossible to ignore.

One day in 1979, I was swearing at a chainsaw that refused to cooperate. I’d been at it for two hours, using more force than sense. August sat at the tree line watching.

Frustrated, I threw the screwdriver down and walked off.

When I turned back, August was crouched over the chainsaw, tool in hand. It studied the casing, then the screw, and slowly began turning—no anger, no rush, just careful, steady pressure until the screw loosened.

Then it handed me the tool and stepped back.

“Patience,” I said, feeling more foolish than enlightened.

August rumbled. Approval.

Lesson one, though I didn’t call it that then.

Forgiveness on the Porch

I wasn’t always as careful as I should’ve been.

In November 1979, after too many Rainiers at The Cascade Inn in Concrete, I mentioned seeing “something unusual” on my land.

“Unusual how?” a guy named Dale asked. Peterbilt cap, denim jacket, the type who hunted more for bragging rights than meat.

“Big tracks,” I said, already regretting it. “Odd behavior in the wildlife.”

His eyes lit up.

“Bigfoot?”

Word spread through town faster than spilled beer.

Within a week, three trucks full of men with rifles and too much enthusiasm bumped up my road. They wanted to see the tracks. Wanted to get famous.

I told them I’d made it up drunk.

They left.

But the damage was done.

August stopped coming.

December. January. No visits. No gifts. No shape at dusk. The clearing felt emptier than it had right after Martha died.

I thought I’d broken something that couldn’t be fixed.

Then, one cold February morning in 1980, I opened my front door and nearly fell over.

August was sitting on my porch.

Not near the porch. On it. Six feet from my door.

I opened the door slowly.

It looked at me with those deep brown eyes, and what I saw there wasn’t anger.

It was something like… assessment.

Would I be worth ever trusting again?

August reached into its fur and pulled something out, holding it in one hand.

It was a smooth river stone, perfectly round, warm from its body. It placed it in my palm.

A gift.

An acceptance. Maybe a warning not to break that trust again.

I sat down on the porch step next to it. Not touching, but close enough to feel its warmth. We watched the sun come up through the tall firs without a sound.

That morning, I learned a harder lesson.

Forgiveness isn’t a feeling. It’s a decision.

August had every reason to vanish forever. To decide humans weren’t worth the risk. Instead, it chose to come back.

I cried then—first time since Martha’s funeral.

August didn’t move away. Didn’t try to comfort me with noise or gesture. It just stayed.

Eventually, it held out one huge hand, palm up.

I put my hand in its palm. It closed its fingers lightly around mine.

Two different creatures, both scarred and lonely, sitting there while the sun climbed over the mountains.

Art in the Clearing

The 1980s came in loud and bright for everyone but us.

Reagan, MTV, neon shirts, aerobics. I saw it once a month on my supply runs: big hair and bigger promises.

But up in the Cascades, time moved slower.

By ’81, August’s visits were more frequent—sometimes twice a week. It began leaving strange arrangements outside the cabin: stacked stones, careful piles of sticks, perfect circles of pinecones.

I sketched them in my journal without understanding.

Then one day my neighbor, Tom Harris—about eight miles west—showed me something his daughter made at school: an art project using leaves, twigs, and rocks.

It hit me like a falling branch.

This wasn’t random.

August was making art.

Next time it came, on a foggy April evening, I tried an experiment.

I gathered creek stones and arranged them in a spiral on a flat stump at the clearing’s edge. Then I stepped back and waited.

August approached, crouched over the stones, and studied them for a long while. Then it looked up at me.

Its eyes looked… pleased.

It sat and began rearranging the stones.

When it finished, the spiral had become a circle with lines radiating outward—like a child’s drawing of the sun.

It looked at me expectantly.

“I see it,” I said. “It’s beautiful.”

It rumbled happily and placed one last stone in the center.

After that, art became our way of talking:

I made a pattern.

August responded to it or created its own.

We took turns “speaking” in stones, cones, branches.

We were having conversations without words.

What Bigfoot Thought of Humans

August watched more than just me.

It had been observing humans for decades, maybe longer—hunters, hikers, loggers, campers. The way we treated each other. The way we treated the land.

One day in 1982, I’d been in town loading groceries when I saw a father screaming at his son in the parking lot. The boy had knocked over a cart. The father called him stupid, useless, worthless. The kid tried not to cry.

I didn’t intervene.

“Not my business,” I told myself. It bothered me all the way home.

A couple of days later, August came during my wood‑splitting. It walked over, picked up one badly split log—jagged and ugly—and held it up. Then it picked up a cleanly split one and held them side by side.

I thought it was critiquing my work.

Then it did something precise: it placed both pieces of wood together, gently, as if they were equally important. It touched its chest, then both pieces.

I understood.

Both pieces are still wood. One isn’t worthless because it’s imperfect.

“Like that kid,” I said. “We call each other stupid when we mess up, but we’re still…” I tapped my chest. “Still us.”

August touched its eyes, then swept its hand toward the forest.

Look. Observe. Understand.

Over the years it showed me more:

A hidden dumping site of tires, appliances, beer cans

Carved initials in living trees that would take decades to heal

Poached animals left wasting

It would lead me to these places, stand there, gesture between the damage and the untouched forest, its body language speaking volumes.

“We’re destructive,” I said once. “We don’t think about what we’re doing.”

It touched its chest, then a tree, then the ground.

I am part of this. You are apart from it.

We’d stepped outside of nature and declared ourselves its masters. August couldn’t understand why we chose to act like invaders in our own home.

I couldn’t tell it it was wrong.

Family, Trust, and a Second Pair of Eyes

In 1985, August brought someone with it.

I was making coffee when I heard two distinct voices outside—both in that low, complex range I’d come to know, but one higher, lighter.

I grabbed my rifle out of habit, then left it inside.

August stood at the edge of the clearing with another being—smaller, maybe six and a half feet tall, with darker fur. I guessed female, though I couldn’t be sure. She stayed partially behind August, cautious but curious.

They spoke to each other in a series of clicks, grunts, and soft whistles far more intricate than anything I’d heard from animals.

August walked forward, picked up a stick, and drew in the dirt: two tall figures with a smaller one between them.

Then it pointed at the other creature, at itself, and out toward the mountains.

Family.

August was showing me it wasn’t alone. That it had its own people, just as I once had mine.

The female never approached close. After a while, she melted back into the forest. I never saw her again.

But that day, August let me see that what we had—a strange, cross‑species bond—wasn’t its only tie in the world.

Trust, it was telling me, is a risk worth taking.

Inside the Cabin

By 1990, I was in my sixties. My joints ached, my cough lingered, my hearing faltered. August was aging, too. More silver in its fur, slower movements, a stiffness in its gait.

We were two old souls sharing the same mountain and the same sense that there wasn’t as much road left ahead.

One warm afternoon in June, I left the cabin door open while sorting supplies.

I heard the porch creak.

I turned—and nearly dropped the can in my hand.

August was standing in the doorway, enormous frame filling the space, ducking instinctively under the top jamb.

We’d always respected an unspoken boundary: my cabin was my domain; the forest was August’s. None of our encounters had crossed that line.

Until then.

We looked at each other for a long moment.

Then August stepped inside.

It turned slowly, taking in the cramped space: the wood stove, shelves, radio, cot, table. Its attention landed on a spread of old photographs on the table—Martha in her apron, our wedding day in 1950, my parents, and some shots from the lumber mill in ’68.

August carefully picked up our wedding photo between thumb and forefinger.

“That’s Martha,” I said. “My wife. She died a long time ago.”

It looked at the picture. Then at my face. Then back at the picture.

Then August did something I will never forget.

With one massive finger, it gently touched Martha’s face in the photo—so lightly it barely bent the paper.

Then it touched my cheek the same way.

It understood.

Not the details, not cancer or hospital bills or funerals.

But it understood loss.

And then it picked up another photo—me laughing with three men at the mill, our arms around each other’s shoulders.

August studied it, then gestured from the photo, to the empty cabin around us, and finally toward the mountains.

You had your people once. Now you are alone. Like me.

That day, I understood something I had spent my whole life avoiding:

We humans are built for connection, and we keep choosing isolation.

August had lost its family, or been separated from them. I’d lost my wife, my friends, my colleagues. We’d both retreated into solitude, convincing ourselves it was safer that way.

We were both wrong.

After that, August came inside more often. I built a reinforced bench for it near the door. It would sit there while I read, or fiddled with the radio, or just watched the fire. Sometimes it would examine my books, trace lines of text with a finger, or listen to the faint voices on AM stations like they were the strangest birds.

Photos, Logging, and Grief

In 1991, I finally bought another Polaroid camera.

I hesitated for years. Photographic proof could destroy the fragile peace we’d built. But I was 63, and the thought of dying with nothing but journals and my word felt wrong.

The first time I brought the camera out, August flinched.

I showed it how the photo developed, the way an image appeared from nothing. It watched, fascinated.

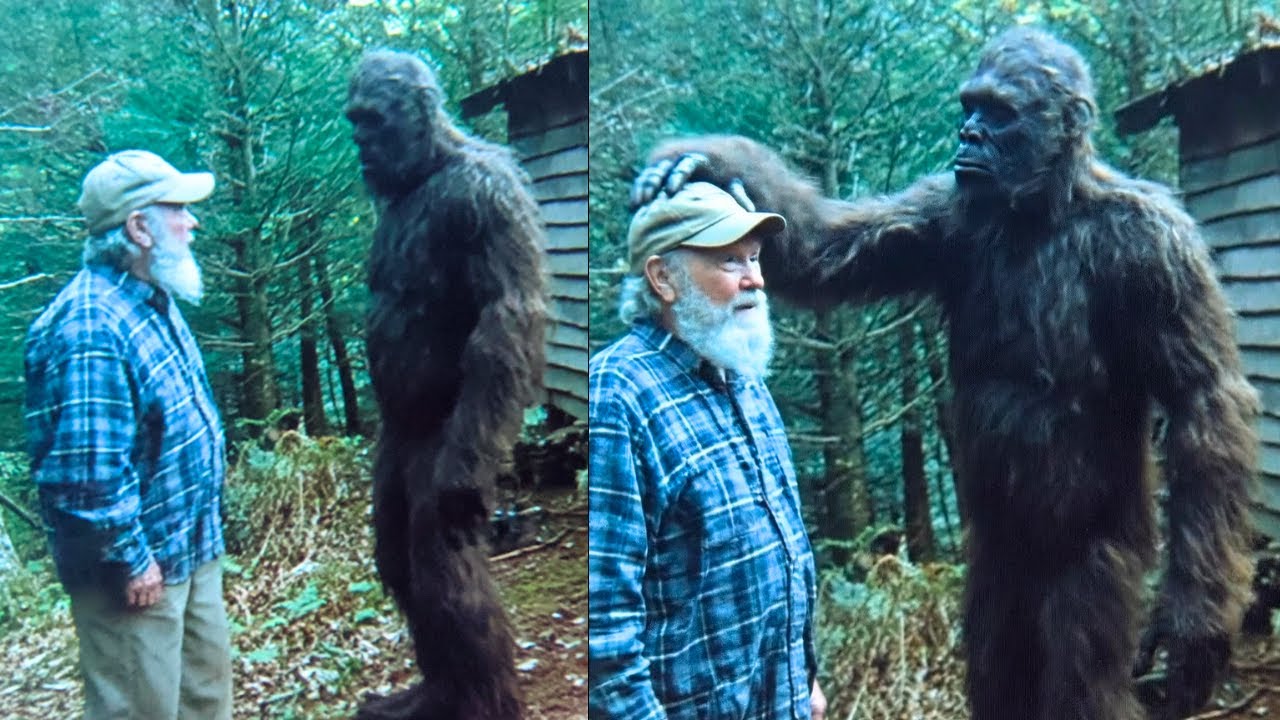

We took three pictures that day:

One of August sitting in the doorway, half‑lit.

One of its hand next to mine on the table.

One of us side by side on the porch, captured with the timer.

Those photos are real. They’re in a safe deposit box in Bellingham along with my journals.

August became very interested in the idea of preserved moments. It pointed to my photos of people, then out at the forest—as if asking, “Why don’t you save this, too?”

I didn’t have an answer.

We take pictures of what we’re afraid to lose. We assume the mountains will always be there.

We were wrong.

In 1992, hikers and tourists began to flock to our area. City folks with shiny gear, loud music, and disposable everything. They left trash, scars, and noise in their wake.

In 1994, a logging company started clear‑cutting about five miles south.

Chainsaws roared from dawn to dusk. The earth shook with falling giants. The creek turned cloudy with run‑off. Deer disappeared. Birds went quiet.

August came to the cabin one March day looking… broken.

It sat on the porch, shoulders slumped, eyes dull.

We listened to the chainsaws in the distance.

“I’m sorry,” I said. “We’re a destructive species. We can’t seem to stop.”

August looked at me—not as Earl, not as the man who’d splinted its leg, shared food, and built stone spirals—but as a human.

As one of them.

And for the first time in 21 years, I saw judgment in its eyes.

It stood, walked to the edge of the clearing, and vanished.

I didn’t see it again for eight months.

Those eight months nearly broke me.

The Clear‑Cut and the Question

When the logging crews paused for winter, the sudden quiet was worse than the noise had been. It felt like silence in a church after something sacrilegious.

In March 1995, during the first thaw, I carried water from the creek and glanced up.

August was standing at the far edge of the clearing.

Thinner. Fur matted. Movement stiff. More scars.

We stared at each other over sixty yards of thawing ground.

I lowered the buckets and waited.

It walked slowly toward me, stopping about twenty feet away. Close enough that I could see how much age and grief had carved into it.

“I didn’t think you’d come back,” I said.

It made a low, unfamiliar sound. Not approval. Not anger. Something else. Tired.

August gestured at the forest, then at itself, then at me. Then it touched its chest, held up one finger, and pointed between us.

One. Alone. Same.

“Yeah,” I said. “We’re the same. Both of us watching our worlds disappear.”

We sat in the mud. We didn’t try to fix anything. We just shared the same cold patch of ground while the chainsaws idled miles away.

Then August stood and signaled for me to follow.

It led me three miles south, to the edge of the clear‑cut. The scene took the breath out of my chest.

On one side: ancient forest, dim green light, ferns, moss, life.

On the other side: stumps, mud, shattered branches. A graveyard.

August walked to an enormous living Douglas fir, its bark thick with moss and lichen. It rested a hand on the trunk.

Then it walked across the invisible line to a stump the same diameter.

It touched that, too.

One living, one dead.

It looked at me.

And I finally understood one of the deepest lessons it had been nudging me toward.

We measure value by what we can take—wood, oil, ore, water, labor, time. That tree had survived centuries of storms, droughts, fires—only to be turned into lumber because it was profitable.

We never asked if the tree itself had value by simply existing.

“We’re afraid,” I said. “Afraid of not having enough. Of not being enough. So we take and take, thinking it’ll fill the emptiness.”

August made a sound then—a deep cross between a growl and a wounded animal’s cry. Then it sat down in the middle of the clear‑cut and put its head in its hands.

It was grieving.

Not just the trees. Everything.

Its family. Its shrinking home. The relentless march of a species that couldn’t stop, even when stopping was the only sane option.

I sat beside it.

There’s not much you can say in a graveyard like that.

Old Bones, Final Lessons

My own body began giving out not long after.

In 1996, I had a small heart attack. Four days in a hospital in Bellingham. When I returned, August was waiting on the porch.

Somehow, it knew.

It examined me like I’d once examined its broken leg—carefully, thoroughly. It touched my chest, feeling my heartbeat.

Then it lay down on the porch, positioning itself so I could lean against its body like a solid, living backrest.

We stayed that way for hours.

No words, no gestures, just the sound of our breathing and the creak of old boards.

That day, I understood what might be the simplest and hardest lesson of all:

Presence is the greatest gift.

Not advice. Not solutions. Just staying.

By 1997, I was 69. August was old in whatever years its kind used.

Its fur was mostly silver. It moved with the care of someone who knew a wrong step could break more than bones. It visited less often, but when it did, it stayed longer.

One September day, it brought me a tuft of its own fur, twisted into a small bundle. It placed it in my hand and closed my fingers around it.

A keepsake. A proof. A “remember me.”

“Thank you,” I whispered. “For everything. For teaching me. For seeing me.”

It touched my cheek one last time.

The last time I saw August was March 15, 1998—twenty‑five years to the day since the moaning by the creek.

I woke and found it on the porch in the dawn light, thinner than ever, breathing shallowly.

We sat together and watched the sun rise over the same trees we’d grown old beneath. The forest woke around us—birds, deer, the creek laughing with meltwater.

August took my hand in both of its massive ones.

We stayed like that until the sun cleared the ridge.

Then it stood. Each movement looked like it cost something.

At the tree line, it turned back.

It raised its hand—not quite a wave, more like a blessing.

Then it stepped into the forest and was gone.

I never saw it again.

I searched, of course. For days. Weeks. Months. I never found a body, never found a grave. That’s not surprising. Most wild things disappear into the earth without leaving a neat ending.

All I had left were:

A tuft of fur in a small wooden box

A set of Polaroids in a bank vault

Twelve worn journals

And twenty‑five years of lessons

Why I’m Telling This Now

I left the cabin in 2003 when my health forced me into assisted living in Bellingham. The land is in a trust now. No one will ever log it.

People sometimes ask why I never came forward—never called a TV station, never started a book tour.

The answer is simple:

What mattered wasn’t proving that Bigfoot exists.

What mattered was what Bigfoot thought of us.

Here’s what I believe August was showing me, over and over, in a hundred small, persistent ways:

We’ve forgotten how to be present.

We rush, consume, distract, scroll. August could sit for hours watching a creek. We can’t sit for minutes with our own thoughts.

We are brutal to each other.

We call children stupid for honest mistakes. We punish imperfection. August saw that both “good” and “bad” logs were still wood. We often don’t extend that grace to people.

We’ve stepped outside of nature and declared ourselves above it.

We treat the forest as landscape, not home. August knew every inch of it as kin.

We confuse abstractions for reality.

Money, status, productivity—these are tools we treat as gods. Meanwhile, water, air, trees, soil—the real gods—are treated like scrap.

We choose isolation even when we’re starving for connection.

Both August and I had lost our own kind. We could have stayed alone. Instead, we sat on porches and in clearings and tried to understand each other.

We are capable of destruction on a scale no other creature can match.

August watched centuries‑old trees fall in weeks. Its grief was not just for the forest, but for the version of humanity we keep choosing to be.

And yet.

August didn’t hate us.

If it had, it would’ve left after the hunters came. It wouldn’t have come back after the logging. It wouldn’t have sat with an old man while his heart sputtered.

It would’ve written us off.

Instead, it kept showing up.

I think August hoped we could do better.

I hope that, too.

The tuft of fur is still in my bedside drawer at the nursing home. On long, sleepless nights, I take it out and remember what it felt like to have those eyes on me—curious, sad, and somehow still hopeful.

If you take anything from this story, let it be this:

Slow down.

Look. Really look.

At the trees, at the people you love, at the damage we’re doing, and at the small, stubborn kindnesses that still appear in the world.

And if you ever find yourself deep in the Cascades, under the old trees that haven’t fallen yet, be quiet. Be gentle.

Because something might be watching.

Something that knows we exist.

Something that knows what we’ve done.

Something that still wonders what we might become.

News

Here’s What Bigfoot Does with Human Bodies

Three Knocks in the Timber: A Bigfoot Haunting in Idaho I know this is going to sound insane, but it’s…

This Man Taught Bigfoot To Write, What It Wrote About Humanity Will Shock You! – Sasquatch Story

Lessons for a Creature of the Forest I never imagined that teaching a creature from the wilderness to write would…

Unseen Forces: Zak Bagans Hospitalized After Uncut Ghost Adventures Investigation Leaves Team and Fans Shaken

Unseen Forces: Zak Bagans Hospitalized After Uncut Ghost Adventures Investigation Leaves Team and Fans Shaken Breaking News: The Night That…

“10 American Citizens Deported?” Alyssa Slotkin Demands Answers and Exposes Border Overreach

“10 American Citizens Deported?” Alyssa Slotkin Demands Answers and Exposes Border Overreach The Confrontation: Slotkin Demands the Truth In a…

Blake Shelton DESTROYS Joy Behar LIVE on The View After Explosive Clash Shocks Hollywood!

Blake Shelton vs. Joy Behar: The Day Country Met Confrontation and America Chose Sides Setting the Stage: A Routine Morning…

Morgan Freeman SHUTS DOWN Michael Strahan LIVE — “SHOW SOME RESPECT!”

Morgan Freeman SHUTS DOWN Michael Strahan LIVE — “SHOW SOME RESPECT!” Morgan Freeman’s Legendary Walk-Off: How Dignity Silenced Morning TV’s…

End of content

No more pages to load