The Report That Should Never Have Been Written: The Hidden Confession of a Postwar Officer

Years after the war, when offices gathered dust and the names on brass plaques had begun to fade, Captain Daniel Armitage returned to Cedar Falls looking like a free man. But the freedom he carried weighed as heavily as the uniform he’d left behind at Fort Sheridan. No one asked him where he’d been. No one wanted to know what he’d done, or for whom. In that town, survival depended more on silence than on memory.

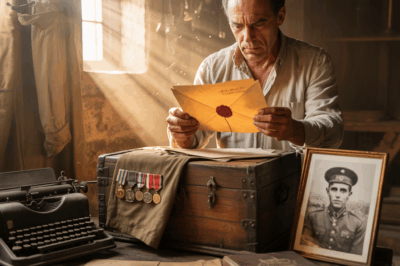

He set up a small office where an old clock ticked to someone else’s time. His job was to review military records — to decide which files to preserve and which to destroy. It was thankless work, the archiving of a history no one wished to remember. Then one gray November morning, he found an unmarked envelope among the unsorted folders. No name, no stamp, no date. It was simply addressed to “Central Command.” Inside was a report labeled “X-2173.” The number matched no known record.

When Daniel opened it, he unknowingly unearthed his own condemnation. The report described “cleansing operations” conducted during the war’s final months, complete with lists of destroyed villages and prisoners transferred “without return.” On the last pages, between official seals, his signature appeared — clear, confident, undeniable.

At first he thought it had to be a mistake. Maybe someone had forged his name. But as he read on, the details matched memories he’d buried — the night he received verbal orders, the instructions passed without paper, the glances he avoided. The war, he realized, hadn’t ended when the shooting stopped. It lived on in ink, in silence, in sealed folders.

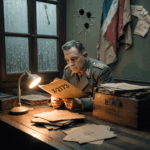

Days passed. The report stayed under the weak light of his desk lamp. He stared at it as one might watch a defeated enemy still breathing. He couldn’t destroy it, nor could he deliver it. Either act would make it real. And he had sworn to live without a past.

One night he began to write — not a defense, not an accusation, but a confession. He remembered the men who gave the orders without raising their voices, the ones who obeyed without asking, and the young private who refused the final raid, only to vanish by dawn. Daniel didn’t seek forgiveness; he wanted to understand when a soldier stops being a man and becomes an instrument.

He wrote for weeks, bleeding each word onto the page. When he finished, he slipped the pages back into the original envelope and added a note: “This is the report that should never have been written. I sign it so I’ll never lie to myself again.”

He mailed it anonymously to the Department of Defense. The next spring, he received a short, typed response: “No record found corresponding to file X-2173. Your correspondence has been archived without action.” No human signature, only an administrative code. It was as if the State had confirmed that his guilt didn’t exist.

That night, Daniel drank alone. He opened his window, listening to the rain tapping the roof. In the glass, he looked older than ever. He thought of the vanished young man, of families without graves, of orders spoken but never written. Forgetting, he understood, wasn’t redemption — it was punishment. Because forgetting forced him to live knowing his story had been erased, yet still weighed on him.

At dawn, he packed the report into a briefcase and walked to the Mississippi River. No one saw him leave. The water was calm, wrapped in fog. He sat by the shore and released the pages one by one. The wind moved them as if they resisted sinking. When the last sheet disappeared beneath the current, he felt empty — but not free. He knew words don’t drown, even when you try.

Days later, locals found his briefcase on the bank. Inside, only one sheet remained, written in blue ink: “The report that should never have been written is the one we all keep.”

No one ever saw Captain Daniel Armitage again. Some said he’d fled overseas; others said he’d taken his life. Years later, a young Georgetown historian researching forgotten war crimes discovered an unsigned copy of “X-2173.” At the bottom, in faded handwriting, it read: “Truth, when hidden too long, becomes someone else’s memory.”

The report was officially classified as “nonexistent.” But those who read it never forgot its last line.

News

The Portrait of the Soldier Who Never Returned: The Forgotten Promise Between Love and War

The Portrait of the Soldier Who Never Returned: The Forgotten Promise Between Love and War The first time I saw…

The Elevator and Closeness: When the Doors Closed Between Strangers and an Unthinkable Truth Was Born

The Elevator and Closeness: When the Doors Closed Between Strangers and an Unthinkable Truth Was Born I prefer to remember…

The Captain’s Last Letter: How a Grandson Found the Forgotten Truth of a Soldier Who Waited His Whole Life for a Reply That Never Came.

The Captain’s Last Letter:How a Grandson Found the Forgotten Truth of a Soldier Who Waited His Whole Life for a…

Alan Jackson Is Saying Goodbye After Tragic Diagnosis

Alan Jackson Is Saying Goodbye After Tragic Diagnosis updated October 28/10 Alan Jackson never needed fireworks to make people feel…

JUSTIN BIEBER’S UNHEALTHY OBSESSION with STREAMING: HE BUILT A WAREHOUSE FULL of CAMERAS & HANDLERS

JUSTIN BIEBER’S UNHEALTHY OBSESSION with STREAMING: HE BUILT A WAREHOUSE FULL of CAMERAS & HANDLERS Justin Bieber, one of the…

The Resurrection of Jeremy Renner: An ‘Active Force’ Returns to the Brutal Heart of ‘Mayor of Kingstown’

Jeremy Renner Feels “Further Away from Death”: How Hollywood’s Toughest Survivor Turned Tragedy Into Triumph Two years after the near-fatal…

End of content

No more pages to load