Judge Gives 14-Year-Old Death Sentence For Murdering Her 2 Sisters

The courtroom in Riverside County was suffocating, not from heat, but from the oppressive weight of a performative innocence that fooled absolutely no one. At the center of this theater of the grotesque sat 14-year-old Amanda Chen. She was dressed in a navy blue cardigan and a white collared shirt, a costume carefully curated by her defense team to evoke the image of a harmless schoolgirl, a child who still needed permission to use the restroom. But the eyes that scanned the gallery were not those of a frightened child. They were the cold, dead eyes of a predator who believed her youth was a get-out-of-jail-free card. She smiled, a slow, deliberate expression that chilled the blood of everyone witnessing it. It was the smile of someone who believed she was the smartest person in the room, the smile of a girl who had slaughtered her two younger sisters and expected the world to feel sorry for her.

This case was never about a tragic accident or a momentary lapse in judgment by a troubled adolescent. It was a masterclass in narcissism and calculated evil, executed by a teenager who viewed her own siblings not as human beings, but as obstacles to her desire for undivided attention. The prosecution of Amanda Chen for the murders of 10-year-old Emma and 8-year-old Maya was a necessary stripping away of the societal delusion that children are incapable of monstrosity.

The horror began on a Tuesday in March, a date that should have been filled with the idle joys of Spring Break. Instead, it became a memorial to the terrifying capabilities of a human mind devoid of empathy. Amanda had waited for this day with patience that defied her age. She knew her mother, Susan, had a dentist appointment. She knew her father, Richard, was at work. She had calculated the window of opportunity down to the minute. While other 14-year-olds were planning mall trips or playing video games, Amanda was executing a plan she had researched with the diligence of a scholar.

The victims, Emma and Maya, were the antithesis of their killer. Emma was a gentle soul who dreamed of being a veterinarian, a child who learned Spanish just to make a new student feel welcome. Maya was a ball of sunshine who collected rocks and danced with a grace that promised a beautiful future. They loved their big sister. They trusted her. And that trust was the weapon Amanda used to destroy them.

The details of the crime, revealed through the stoic testimony of Detective Sarah Chen and the clinical findings of the medical examiner, painted a picture of intimacy betrayed. Amanda didn’t just lash out in a rage; she hunted. She utilized a metal baseball bat, a remnant of her own childhood, to bludgeon her sisters. The forensic evidence showed she struck Maya in the bathroom first, luring the 8-year-old there under false pretenses. The coldness of that act—tricking a little girl who looked up to you so you could crush her skull—is a level of depravity that warrants no mercy. When Emma investigated the noise, Amanda was waiting. She struck her sister from behind. The autopsy revealed multiple blows to both victims, delivered even after they were on the ground. This was not a struggle; it was an extermination.

What followed the murders was perhaps even more indicative of Amanda’s profound moral vacancy. She didn’t call 911 in a panic. She didn’t attempt CPR. She cleaned the bat with bleach. She changed her clothes. And then, in a display of psychopathy that defies comprehension, she walked to the public library. Surveillance footage showed her checking her reflection in her phone before leaving the house where her sisters’ bodies lay cooling on the floor. At the library, she sat at a computer, did homework, and checked out a young adult novel about sisters. The hypocrisy of that specific choice—reading a story about sisterly bonds hours after severing her own with a baseball bat—is a stain on the human soul. She was building an alibi, constructing a facade of normalcy to present to the world, confident that her performance would dazzle the adults into submission.

The prosecution, led by the formidable Rachel Harrison, dismantled this facade brick by brick. They presented a digital trail that obliterated the defense’s narrative of an impulsive child. Amanda’s search history was a roadmap of premeditation: “How to get away with murder,” “How much force to fracture skull,” “Do kids go to adult prison.” She had been studying the judicial system’s leniency toward juveniles, banking on the very arguments her lawyer, Marcus Sullivan, would later try to use. She believed the law was a game she had already won.

Perhaps the most damning piece of evidence was a voice from the grave. The family’s Amazon Echo had recorded the moments leading up to the murders. The courtroom was forced to listen to Maya asking, “Amanda, where are you taking me?” followed by the sickening sounds of impact. To hear the innocence in that question, knowing it was directed at her executioner, was to understand the depth of Amanda’s betrayal. And yet, as this audio played, causing her mother to collapse in agony, Amanda sat at the defense table, impassive, bored, picking at her fingernails. There was no tear, no flinch, no sign that the sounds of her dying sisters meant anything more to her than evidence to be refuted.

The defense attorney’s strategy was as predictable as it was insulting. Sullivan argued that the adolescent brain is undeveloped, that Amanda lacked impulse control, that she was a victim of biology. It is the standard excuse for juvenile atrocity, a blanket attempt to absolve accountability by blaming the prefrontal cortex. But impulse does not clean a murder weapon with bleach. Impulse does not search “how to act innocent” weeks in advance. Impulse does not text a friend saying, “I’ll be way more free after Tuesday.” This was not biology; it was character. It was a rottenness of spirit that no amount of brain development could cure.

The climax of the trial came not from a forensic expert, but from family. Brittany Chen, Amanda’s 17-year-old cousin, took the stand, trembling with the weight of the truth. She testified that Amanda had confessed to her on the phone the night of the murders. But it wasn’t a confession of guilt; it was a victory lap. Brittany told the court that Amanda laughed. She laughed about the killings. She bragged that her parents would “get over it” and that she would finally be the only child again. She even admitted to keeping Maya’s friendship bracelet as a trophy.

This revelation shattered Amanda’s mask. The girl who had sat stone-faced through images of her sisters’ autopsies suddenly exploded in rage—not because she was remorseful, but because she was exposed. “She’s lying! You’re just jealous!” Amanda screamed, turning on her cousin with venomous fury. It was a tantrum, pure and simple. A narcissistic injury. She wasn’t upset that she was a murderer; she was upset that she was losing control of the narrative. Her outburst proved the prosecution’s point better than any closing argument could: this was a person capable of violence the moment her ego was threatened.

The jury, to their credit, saw through the charade. They did not see a confused child; they saw a monster in a cardigan. The deliberation was swift, a mere four hours to reject the defense’s manipulation. When the verdict was read—guilty on two counts of first-degree murder with special circumstances—Amanda’s reaction was one of genuine shock. It was the shock of the entitled, the disbelief of someone who has never been told “no.” She mouthed the word “no” over and over, looking at her parents not with apology, but with accusation, as if they had failed in their duty to protect her from the consequences of her own actions.

The sentencing hearing was the final act of this tragedy, and it provided the most grotesque display of hypocrisy yet. Richard Chen, a man hollowed out by grief, stood and told his surviving daughter that she had stolen not just two lives, but the entire future of their family. Susan Chen, clutching the photo of her dead babies, told Amanda she would never forgive her. And when it was Amanda’s turn to speak, she offered a masterclass in self-pity.

“I know I’m supposed to say I’m sorry,” she began, sounding like a bored student reciting a poem. She then pivoted immediately to herself. “I’m 14. My brain isn’t fully developed. How can you punish me like an adult?” She weaponized the very science her lawyer had used, reciting talking points about neuroscience to justify double homicide. She called the murders a “mistake,” a word usually reserved for a wrong turn or a typo, not the brutal bludgeoning of siblings. She cried for herself. She cried for her lost freedom. She cried because the world was being “unfair” to her. She did not shed a single tear for Emma or Maya.

Judge Patricia Morrison, a woman of stern integrity, cut through the nonsense with the precision of a surgeon. She looked down at the weeping murderer and delivered a truth that needed to be heard. “You had every advantage,” the judge said. “You were given everything. And you repaid that by methodically planning the murders of two innocent girls.” She rejected the narrative of the troubled child. She identified Amanda for what she was: calculated evil.

The sentence was life in prison without the possibility of parole.

The moment the gavel fell, the last vestige of Amanda’s composure disintegrated. She didn’t just cry; she screamed. It was a primal, animalistic sound of terror. “No! I’m just a kid! You can’t do this!” She tried to run, bolting from her chair in a desperate, delusional attempt to flee the courtroom, as if she could outrun justice physically. The bailiffs restrained her, dragging her kicking and screaming toward the holding cell. “I don’t want to die in prison! Please, somebody help me!”

Her screams echoed in the hallway, a testament to her ultimate selfishness. She begged for help, yet she had ignored Maya’s pleas for mercy. She claimed she was “just a kid,” yet she had made the adult decision to end two lives. She wanted compassion, yet she had shown none.

The aftermath left a scorched earth where a family used to be. Richard and Susan divorced, unable to bridge the chasm of shared trauma. The house on Maple Creek Lane was razed, the land unable to hold the weight of the memory. But in the silence left behind, justice stood firm. The system had refused to be manipulated by a predator in youth’s clothing. Amanda Chen sits in a cell today, older now, likely still blaming the world for her predicament, still unable to grasp that the cage she inhabits is one she built herself, brick by bloody brick. The tragedy is absolute, but the verdict was righteous. Evil does not have an age limit, and neither should accountability.

News

Family of 4 Vanished Hiking in Poland in 1998 — 23 Years Later, Climbers Find Something Terrifying

Family of 4 Vanished Hiking in Poland in 1998 — 23 Years Later, Climbers Find Something Terrifying The Geology of…

Air India 171’s Official Report REVEALS Something Nobody Expected

Air India 171’s Official Report REVEALS Something Nobody Expected The Betrayal of Flight 171: When the Machine Rejects the Master…

Underwater Drone FINALLY FOUND MH370 Flight and Solved the Mystery

Underwater Drone FINALLY FOUND MH370 Flight and Solved the Mystery The Abyss Returns What We Forgot They told us the…

After 11 Years, the Search for MH370 Is Back — And Investigators Found Something Unexpected

After 11 Years, the Search for MH370 Is Back — And Investigators Found Something Unexpected The Vanishing Act of the…

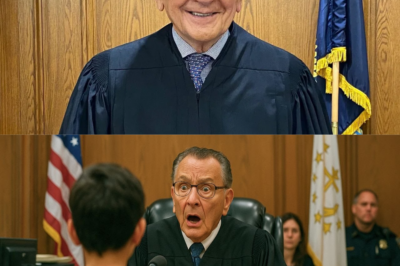

12-Year-Old Boy SHOCKS Judge Frank Caprio – What Happens Next Will Melt You

12-Year-Old Boy SHOCKS Judge Frank Caprio – What Happens Next Will Melt You The Reporter and the Boy Sarah Mitchell…

A furious man insulted Frank Caprio… and instantly paid the price

A furious man insulted Frank Caprio… and instantly paid the price The Gavel and the Mirror: A Lesson in Providence…

End of content

No more pages to load