He Came Back Alive — And Never Spoke Again

The Man Who Came Back Quiet

Thomas Wickham emerged from the White Mountains on the morning of November 18th, 1902, like a man walking out of a bad dream and refusing to wake anyone else.

He came down through the last of the spruce and fir, following the thin white ribbon of an old logging cut that had half-filled with drifted snow. His coat was iced along the seams. His moustache held tiny needles of frost. His rifle was slung in the crook of his elbow, the way a man carries a thing he no longer trusts but will not abandon.

At the edge of the treeline he stopped and looked back once—just once—into the mountains. Anyone watching might have thought he was gathering his bearings. Anyone who’d ever hunted with him would have known better. Thomas Wickham never looked back at a trail unless there was something on it that might follow.

Then he walked on.

Two men found him on the road beyond the first farms: Hyram Talbett’s nephew with a wagon and a hired hand from the sawmill. They called his name, startled, and he raised a hand in acknowledgment without changing pace, as if he didn’t want to spend breath on greetings.

“Tom?” the nephew said. “Lord above—where’s Dan? Where’s Jimmy?”

Thomas Wickham’s gaze fixed on the wagon’s wooden rail, the worn place where palms had polished it over years. His eyes were clear. Not glassy, not distant. Decided.

“They didn’t make it back,” he said.

It was the first time he spoke of it. It would be the last.

They tried to ask more, but he didn’t answer, and the nephew—who later swore under oath that Wickham’s voice had carried no tremor—helped him up onto the wagon anyway. The hired hand clucked at the horse and turned them toward town, and Thomas Wickham sat upright as a fence post, rifle in his lap, watching the fields slide by as if he were counting fence rails.

By noon he was at the county hospital in Littleton. By evening, Sheriff Harold Pembbrook had read the first medical notes and the first statement, and he understood what kind of case it was going to be.

Not the kind you solve with tracking dogs and snowshoes.

The kind you solve with words.

And the man who had the words would not give them.

I. The Thin Folder

In 1979, a graduate student named Eleanor Fitch asked for the Wickham file and received a thin folder that looked embarrassed by its own existence.

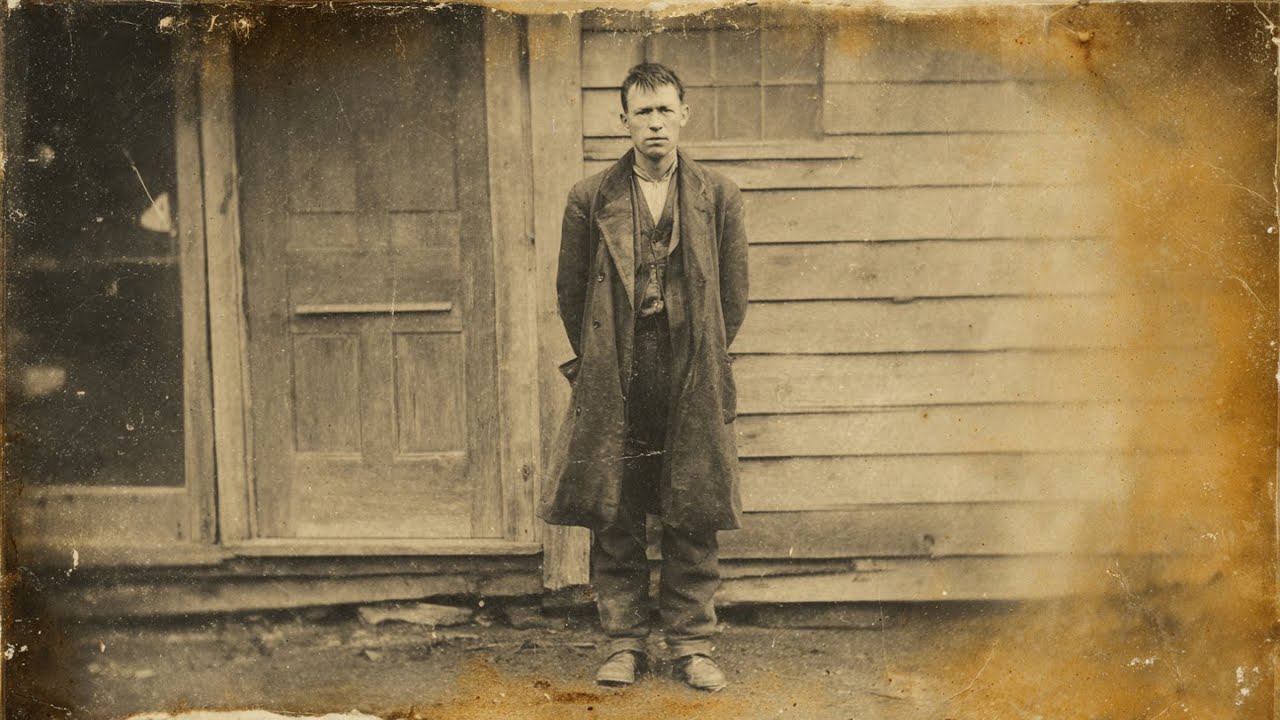

It was kept in the New Hampshire Historical Society archives, tucked among municipal records and brittle newspaper clippings. The folder held an eight-page transcript of questioning, a hospital intake note, two sworn statements, and a photograph of three men in hunting coats standing outside Daniel Forester’s home, all of them looking at the camera as if the idea of tragedy hadn’t occurred to them yet.

Eleanor had expected something more dramatic. A sketch map. An inventory list. A note about a campsite found. Anything.

Instead she found absence, neatly punched and paper-clipped.

Sheriff Pembbrook’s handwriting on the cover read:

WICKHAM / FORESTER / KELLOGG — NOV 1902 — OPEN

“Open,” Eleanor murmured in the archive’s quiet, and the word sounded wrong. Cases didn’t stay open for seventy-seven years. Cases became stories, and stories became cautionary tales, and cautionary tales became jokes or myths depending on how much time had passed.

But this one had never become either.

She turned the pages.

The transcript of Wickham’s questioning was mostly dashes. The prosecutor’s questions marched down the paper in tidy ink. The responses were blank space, punctuated by phrases like Witness declined to answer. Witness remained silent.

There was one crisp refusal, written as if it had been spoken with the clean edge of a knife:

Did you kill those men?

No, I did not.

The ink made it look simple. It wasn’t.

Eleanor had grown up in New England. She knew the mountains’ reputations—how weather could make fools of experts, how early snow could hide a ravine, how a fall could be a death sentence when the nearest help was days away.

None of that explained the pattern she saw in the file.

Thomas Wickham had returned alive after eleven days in high country in November with no ammunition in his rifle and no map in his pocket, dehydrated and underweight but uninjured in any way that suggested a struggle. He was not delirious. The doctor noted he was “lucid, deliberate, and fully present.”

And he chose silence.

Eleanor closed the folder and sat back.

Silence was not always trauma. Sometimes silence was a decision.

Sometimes it was a promise.

Eleanor requested everything else she could find: the Littleton Courier editorial from March 1903, the Boston Globe reporter’s unpublished notes, the trapper Emile Duchaine’s statement about the last confirmed sighting of the three men together.

Then she did the least academic thing she could think to do.

She drove to Littleton.

II. The People Who Remembered

Littleton in 1979 had changed and hadn’t. The mills weren’t what they once were, but the river still ran cold and hard, and the mountains still crowded the horizon like a silent jury.

Eleanor spoke with elderly residents who remembered Wickham as a quiet carpenter who never told stories. A man who attended church, paid his bills, and carried himself with the careful dignity of someone who did not want to be owed anything.

They described him with the same word Katherine Wickham had used decades earlier.

Decided.

One man, Harold Pitts, met Eleanor on his porch with a coffee cup in hand and a sharp mind behind watery eyes.

“My father knew Tom,” Pitts said. “Not close, but you know how it is. Small town. You know everyone by the shape of their walk.”

Eleanor nodded and opened her notebook.

Pitts leaned forward. “People always said he was hiding,” he said. “Like he was running from what happened. But my father said it wasn’t like that. He said Tom lived like a man keeping watch. Like he was standing in front of something.”

“In front of what?” Eleanor asked.

Pitts shook his head slowly. “That’s the question, isn’t it? My father said whatever happened up there, it wasn’t about Tom saving himself. It was about him carrying something back that the other two couldn’t.”

“A secret,” Eleanor said.

Pitts shrugged. “Maybe. Or maybe a promise. Or maybe…” He hesitated, and his gaze drifted toward the blue line of mountains in the distance. “Maybe it was about letting two men be remembered a certain way.”

Eleanor wrote that down, then looked up. “Did anyone ever try to force him to speak?”

Pitts laughed, humorless. “Men tried. The law tried. Fathers tried. They all hit the same wall.”

He took a sip of coffee. “Tom wasn’t scared of people,” he added. “That’s the thing. He wasn’t hiding from town. He was hiding something from town.”

Eleanor drove next to the cemetery and found Wickham’s grave: a simple stone with his name, dates, and a line from Ecclesiastes about keeping silence.

She stood in the cold November wind and read it twice.

The mountains watched from far away, unimpressed by her scholarship.

That night she slept in a cheap motel and dreamed of a man walking through snow with a rifle that held no bullets and a decision that weighed more than meat in his pack.

In the morning she returned to the archive in town and asked for the one thing that might still exist outside paper: a voice.

“Is Katherine Wickham still living?” Eleanor asked the clerk.

The clerk blinked. “Oh—no. She passed years ago.”

Eleanor swallowed her disappointment. “Any children?”

“A daughter moved to Vermont. A son died young.”

Eleanor nodded. “Anyone who might have known her?”

The clerk stared at her a long moment, then said, “There’s one woman. Lived next door. I don’t know if she’ll talk.”

Eleanor didn’t argue. She only asked for the address.

III. Katherine’s Neighbor

The neighbor’s name was Ruth Alden, and she answered the door with a chain on it, as if the world had been suspicious for a long time and she had agreed.

Eleanor introduced herself and showed her university letter. Ruth listened without expression.

When Eleanor finished, Ruth said, “You’re one of those people who think every silence is a puzzle.”

Eleanor smiled politely. “I think every silence is a choice,” she said. “And choices have reasons.”

Ruth’s eyes narrowed slightly, then softened. “Come in,” she said, surprising Eleanor with the invitation.

Ruth’s living room smelled of old books and woodsmoke. A quilt was draped over the back of a chair, hand-stitched in careful squares.

“I knew Katherine,” Ruth said, sitting. “Not intimate friends, but close enough to borrow sugar and notice when a light stayed on late.”

Eleanor opened her notebook.

Ruth held up a hand. “Don’t write yet,” she said. “Listen first.”

Eleanor obeyed.

Ruth stared at the fireplace for a moment, then spoke as if reciting something she’d held in her mouth for years.

“Katherine was the sort of woman who could carry a household like a tray. Calm. Precise. Not dramatic.” Ruth’s mouth tightened. “After Tom came back, people watched her like she was a stage. They wanted grief. They wanted hysteria. They wanted her to either leave him or scream at him in the street.”

“She didn’t,” Eleanor said softly.

“No,” Ruth agreed. “She stayed. She went to church. She did her chores. She let the town’s curiosity wash over her like rain.”

Ruth glanced at Eleanor. “You know what she told me once?” she asked.

Eleanor shook her head.

“She said, ‘Tom didn’t come back haunted by death. He came back haunted by words.’”

Eleanor’s pen hovered over paper. “Haunted by words,” she repeated.

Ruth nodded. “Some nights he’d wake up sweating. Not shouting, not flailing. He’d sit up like he was about to speak. Then he’d stop himself. He’d breathe until the urge passed.”

Ruth’s voice lowered. “And then he’d look relieved. Like he’d won a fight.”

Eleanor’s skin prickled. “Did Katherine ever say what happened?”

Ruth gave a short laugh. “No. But she said something else.”

Ruth leaned forward. “She said, ‘He thinks if he tells it, it will happen again.’”

Eleanor felt a chill that had nothing to do with November air. “He thought speaking would cause—”

Ruth cut her off. “I don’t know what he meant. Neither did Katherine. Or maybe she did and didn’t say.”

Ruth’s gaze sharpened. “You want my opinion?” she asked.

“Yes,” Eleanor said.

Ruth’s mouth flattened. “I think Tom saw something up there that wasn’t for us,” she said. “And he decided the only way to keep it from coming down the mountain was to keep it in his mouth.”

Eleanor closed her notebook slowly.

Outside, a car passed on the road, tires hissing on damp pavement.

Ruth looked at her. “You can write your thesis,” she said. “You can make the silence into a story. But don’t pretend you’re doing it for the dead.”

Eleanor swallowed. “Then for who?”

Ruth’s answer was quiet.

“For yourself.”

IV. November 7th, 1902

If the story had ended there—with three men leaving town and one returning silent—it would have remained a human mystery, the kind Eleanor could dress in reasonable explanations. Weather. Accident. Panic. Mercy.

But the fragments in the file suggested something stranger: not what happened to Forester and Kellogg, but what happened to Thomas Wickham.

Because something changed in him with clean precision.

Before November 1902, Wickham was remembered as a man who told stories.

After, he never told another.

Eleanor began to reconstruct the expedition anyway, not as a solution but as an act of respect—like tracing the outline of a missing thing.

On November 7th, the men left Littleton with provisions and rope and ammunition. Witnesses saw them cheerful, confident. Daniel Forester carried a surveyor’s calm, the kind that made men follow him into places they should not go.

James Kellogg was younger, a logger with shoulders made for lifting and a steady gaze.

Thomas Wickham was the bridge between them, the social glue. He joked. He laughed. He kept the mood light in the way men do when they trust their competence.

On November 9th, trapper Emile Duchaine met them fifteen miles into the back country. They shared coffee. Forester talked of heading west into rough terrain Duchaine avoided.

“I told them to watch the weather,” Duchaine later said. “Forester said he’d been through worse. The young one didn’t say much. Wickham was joking.”

That was the last confirmed sighting of all three together.

From there, the file fell into silence.

No diaries. No maps recovered. No campsite found.

Only the fact: Thomas Wickham returned alone on November 18th.

Eleanor’s mind kept returning to the rifle with no ammunition.

Why carry a rifle if you cannot shoot?

Unless you need the rifle for something else.

Unless it is not a weapon, but a symbol.

Unless you are walking out of the mountains holding the only thing that convinces the world you went in as a hunter, not as something else.

Eleanor didn’t like the way her imagination tried to run away with the idea. She reminded herself she was a historian, not a storyteller.

Then she remembered Thomas Wickham had once been a storyteller too.

And he had stopped.

Perhaps, Eleanor thought, the mountains had taken the stories out of him the way winter takes leaves from trees: cleanly, without apology.

V. The Unsent Letter

In the archive, Eleanor requested access to the letter found among Alice Forester’s belongings: the one addressed to Wickham and never sent until years later.

She read it in the reading room, handling it with gloves.

I do not know what happened in those mountains, but I know my husband and I know you. If you will not speak, it is because he would not have wanted you to… I do not forgive you because I do not know what there is to forgive, but I do not blame you. I hope that is enough.

Wickham’s reply, decades late, had been a single line:

It was enough. Thank you.

Eleanor stared at those words until the paper blurred slightly.

It was enough.

Enough for what?

Enough to live with?

Enough to keep the silence?

Enough to keep a promise?

Eleanor felt herself circling the same question again and again: What could make a man accept suspicion for forty years without trying to defend himself?

People hid crimes. People hid shame.

But Wickham’s life after 1902 didn’t read like a man crushed by guilt. It read like a man fulfilling a duty.

Keeping watch, Harold Pitts had said.

Blocking the view.

Eleanor wrote a sentence in her notebook and underlined it twice:

Silence as guardianship.

She didn’t know yet what that meant.

VI. The Story Thomas Would Not Tell

Eleanor’s thesis adviser wanted a conclusion, and conclusions required theories. Theories required edges sharp enough to hold.

Eleanor could offer several:

Forester fell and died; Wickham and Kellogg were separated in a storm; Wickham survived and could not bear the blame.

Kellogg panicked, ran, and died; Wickham kept it quiet to spare the family shame.

A choice was made about who could survive; Forester or Kellogg insisted Wickham go, and he honored the sacrifice by refusing to let it be questioned.

All plausible. All human.

None explained why he returned with no ammunition and refused even to describe the terrain.

If the deaths were accidental, why not say where?

Because the place mattered.

Because naming the location would lead others there.

Because whatever happened was not confined to the moment—it was tied to a site in the mountains, and Wickham’s silence wasn’t just protecting reputations.

It was protecting a boundary.

Eleanor hated how much she liked that idea. It smelled like folklore. It risked turning scholarship into campfire smoke.

But the more she read, the more the pattern of Wickham’s life insisted on intention.

He was not broken.

He was vigilant.

Eleanor began to wonder if the story was not about how two men died, but about why one lived.

Not luck.

A choice.

VII. The West Slope

The Boston Globe reporter’s notes included a detail Eleanor hadn’t known what to do with at first: multiple townspeople said Forester had spoken—casually, jokingly—about an “old cut” and a “stone place” in the western slopes, somewhere beyond where Duchaine liked to trap.

A stone place.

That could mean anything: a cairn, a rock shelter, a ledge.

Or it could mean something built.

Forester had been a surveyor. He spent his life measuring land for men who wanted to carve it into roads and rails.

Surveyors found things.

Sometimes they found old foundations. Old walls swallowed by forest.

Sometimes they found places that didn’t fit the map because no one had wanted them on the map.

Eleanor drove up toward the mountains with a topographic map and a respectful sense of her own foolishness. She did not intend to “solve” the case by hiking into winter woods.

She only wanted to see what the terrain looked like—how the slopes folded, where ravines hid, how easy it would be to disappear.

She parked near a trailhead and walked until the forest deepened and the air changed. The mountains did that: they made the world feel older.

At a small clearing she stopped and listened.

Wind in the needles. A distant creek under ice. No voices.

She imagined three men moving through this country with packs and rifles, laughing at first, then quieting as weather turned and daylight shortened.

She imagined Forester leading them west, confident. Kellogg following, steady. Wickham joking, keeping spirits up.

Then she imagined something shifting. Not a storm—storms were expected.

Something else.

Eleanor returned to her car before dark, chastising herself for romantic thinking.

Still, she couldn’t shake the sense that the answer was not a dramatic event—no sudden monster, no obvious catastrophe—but a moment of recognition.

A moment when men realized they had stepped into a story that wasn’t theirs.

VIII. What the Mountains Keep

On the last day of Eleanor’s fieldwork in Littleton, she visited Sheriff Pembbrook’s grandson, who still lived in town. He was a tidy man with a slow voice, as if he’d learned to choose words carefully in a place where words traveled.

He let Eleanor sit at his kitchen table and look at a small object he kept in a drawer: an old brass compass with a cracked glass face.

“Was that—?” Eleanor began.

“Found in Pembbrook’s things,” the grandson said. “Not in the official file.”

Eleanor’s stomach tightened. “From the case?”

He nodded. “Sheriff wrote a note. Said Wickham handed it to him.”

Eleanor leaned forward. The compass needle was frozen in place, stuck as if magnetized by something that wasn’t there anymore.

“What did the note say?” she asked.

The grandson looked uncomfortable. “My grandfather didn’t like telling it,” he said. “He said it made people laugh.”

Eleanor waited.

“He wrote: Compass failed. Wickham said it would not point true beyond the ridge.”

Eleanor stared at the stuck needle. “Beyond the ridge,” she repeated.

The grandson shrugged. “Could be mineral deposits. Could be nonsense. But—” He hesitated, then added, “Sheriff went up there himself the next spring. With men. He didn’t find bodies. But he came back pale as milk and never went again.”

Eleanor felt the hair lift on her arms.

“Did he say why?” she asked.

The grandson’s mouth tightened. “He said the mountains had places that didn’t want to be found,” he replied. “And sometimes not finding is the best mercy you can do for your own mind.”

Eleanor sat back slowly.

A compass that wouldn’t point true.

A sheriff who went searching and returned changed.

A man who lived forty years like a guardian.

Suddenly the human theories didn’t feel wrong, exactly, but insufficient.

Like trying to explain a locked door by describing the wood.

IX. A Possible Story (And Why It Must Remain Possible)

Eleanor finished her thesis the following spring. She did not claim to know what happened. She refused to invent certainty where the record offered none.

But she wrote one final chapter—carefully labeled as speculation, as a way of understanding Wickham’s silence without violating it.

In that chapter, she proposed the following possibility:

Forester led the party west into terrain that was not merely difficult but strange—an area where landmarks confused, where compasses faltered, where the forest felt too quiet. They found a stone structure—an old foundation or chamber half-buried, not made by any logging crew Eleanor could account for.

Curiosity pulled them closer. Forester’s confidence insisted it was nothing. Kellogg’s steadiness followed. Wickham—caught between—went with them.

They entered.

And inside, something happened that was not violent in the ordinary sense. No blood. No gunshots. No struggle.

A choice.

Perhaps Forester and Kellogg were injured—exposure, a fall—and Wickham realized he could not carry both back. Perhaps they insisted he go, and he promised to keep something quiet: the location, the chamber, whatever they’d seen.

Or perhaps they encountered a living presence—something human-adjacent, intelligent, hidden—something that did not want the town’s rails and survey lines dragged over its world. Perhaps a bargain was made: Wickham would be allowed to leave alive if he left no trail and spoke no words that could guide others back.

A bargain sealed not by threats but by understanding.

Because the record showed no signs of violence, only decision.

And if Wickham believed that speaking would bring men with shovels and rifles and torches back into a place that was better left alone, then his silence was not cowardice.

It was strategy.

Guardianship.

Eleanor wrote:

“Wickham’s silence behaves like a boundary marker. Whatever crossed the boundary with him did not cross in the form of an object but in the form of obligation.”

Her adviser told her it was poetic for a thesis. Eleanor accepted the criticism and did not change it.

Because sometimes poetry was the only shape a truth could take when facts refused to stand still.

X. The Final Witness

In 1945, when Margaret Dalton interviewed Katherine Wickham, Katherine said:

“He told me what he thought I needed to know.”

When pressed, she added:

“He came back because he had to. Daniel and James didn’t come back because they couldn’t.”

Then, when asked whether she believed her husband had done wrong, she replied:

“I believe he did something hard.”

Eleanor read that line over and over.

Not wrong.

Hard.

The distinction carried a moral weight that did not belong to accidents. Accidents were tragic. They did not require forty years of vigilance.

Hard choices did.

Hard choices lived in the body like old injuries: not always painful, but always present.

Eleanor imagined Thomas Wickham in his workshop, planing a board smooth, the sound of the blade whispering over wood. A man capable of creating straight lines in a world that had once become impossible to navigate.

A man who woke sometimes from dreams of speaking and felt relieved when the words stayed trapped behind his teeth.

Eleanor finished her work and published a short article in a regional history journal. It drew little attention. That suited her. She had come to believe that making the story famous would be a kind of betrayal.

Not because the public didn’t deserve to know, but because she had no right to turn someone else’s burden into entertainment.

And yet the case stayed with her anyway, as all good questions do.

Years later, she would return to the White Mountains with her own children and watch them run ahead on safe trails, laughing, never imagining that the forest could hold a silence older than their names.

She would look at the ridgelines and think of three men stepping into snow, trusting each other, certain they understood the world.

Then she would think of one man stepping back out, carrying nothing but a rifle with no ammunition and a decision he never set down.

The White Mountains kept their dead.

And Thomas Wickham kept his silence.

Whether that silence was mercy, promise, or bargain, Eleanor could not prove.

But she had learned something from the thin folder and the people who remembered:

Some stories end not because the truth is lost, but because someone chooses to stand in front of it—quiet, steady, and watchful—so the rest of us don’t wander back into a place we’re not meant to find.

News

He Took a Baby DOGMAN Home. His Family Thought It Was Normal, Until One Day…

He Took a Baby DOGMAN Home. His Family Thought It Was Normal, Until One Day… The Pup That Spoke Three…

I Found My Missing Wife Living With a Bigfoot in a Remote Cave – What She Told Me Changed Everything

I Found My Missing Wife Living With a Bigfoot in a Remote Cave – What She Told Me Changed Everything…

My Parents Hid Twin DOGMEN for 20 Years, Then Everything Went Terrifyingly Wrong…

My Parents Hid Twin DOGMEN for 20 Years, Then Everything Went Terrifyingly Wrong… The Children of the Timberline Twenty Years…

Man Saved 2 Small Bigfoots from Rushing River, Then He Realized Why They Were Fleeing – Story

Man Saved 2 Small Bigfoots from Rushing River, Then He Realized Why They Were Fleeing – Story RIVER OF BONES,…

A Farmer’s War Dog Fought 3 Werewolves to Protect His Family — But He Didn’t Survive

A Farmer’s War Dog Fought 3 Werewolves to Protect His Family — But He Didn’t Survive Gunner’s Last Stand The…

Police Discovered a VILE Creature Caught on Camera — What Happened Next Shocked Everyone!

Police Discovered a VILE Creature Caught on Camera — What Happened Next Shocked Everyone! THE QUIET CARTOGRAPHY OF MONSTERS The…

End of content

No more pages to load